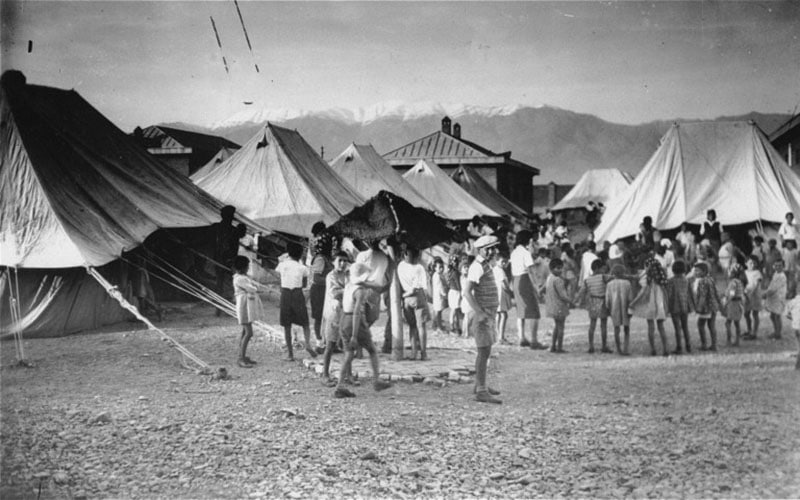

Polish Jewish refugees in a tent orphanage in Tehran, 1942. Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum/David Laor.

Polish Jewish refugees in a tent orphanage in Tehran, 1942. Photo credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum/David Laor.

“To us … it is a heaven.” These were the words of Warsaw-born Rabbi and scholar Hayim Zeev Hirschberg in the early 1940s in reference to an Asian country that, at the time, was saving the lives of thousands of Jewish and non-Jewish refugees during the Holocaust.

Incidentally, Hirschberg wasn’t referring to Mandatory Palestine or China or Japan but to…Iran.

Yes, Iran, whose regime in the past four decades has executed Jews at home, paid terrorists — from Jerusalem to Buenos Aires — to kill Jews abroad, repeatedly denied the Holocaust and hosted Holocaust cartoon contests in Tehran (as well a 2006 event titled “The International Conference to Review the Global Vision of the Holocaust” that featured former Ku Klux Klan Imperial Wizard David Duke).

But Iran after the 1979 Islamic Revolution doesn’t resemble the Iran of the early 1940s, which was led from 1941-1979 by the secular, Westernizing Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who succeeded his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi. In 1941, the British and Soviets invaded Iran and deposed Reza Shah, who was friendly to Nazi Germany. Anglo-Soviet troops quickly brought his pro-British son to power.

Starting in 1942, the port city of Bandar Pahlavi (now called Bandar-e Anzali) received up to 2,500 Polish refugees per day, totaling 116,000 (5,000-6,000 of them were Jewish, and of that number, nearly 1,000 were children).

One of those children, Hannan (then 14), was the father of Israeli author and CUNY Professor Mikhal Dekel. “Pahlavi was the first city my father encountered since the beginning of the war that had not been ravaged by war and hunger,” Dekel wrote in her magnificent book, “Tehran Children: A Holocaust Refugee Odyssey” (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019). In meticulously-researched detail, the work retraces the 13,000-mile journey of Dekel’s father and several of his family members from Poland, shortly before the Nazi invasion in 1939, to Siberia, where they nearly starved to death, to Uzbekistan and, eventually, to Iran (then under British rule) in August 1942.

One of those children, Hannan (then 14), was the father of Israeli author and CUNY Professor Mikhal Dekel. “Pahlavi was the first city my father encountered since the beginning of the war that had not been ravaged by war and hunger,” Dekel wrote in her magnificent book, “Tehran Children: A Holocaust Refugee Odyssey” (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019). In meticulously-researched detail, the work retraces the 13,000-mile journey of Dekel’s father and several of his family members from Poland, shortly before the Nazi invasion in 1939, to Siberia, where they nearly starved to death, to Uzbekistan and, eventually, to Iran (then under British rule) in August 1942.

On March 17, Dekel will share her thoughts on the journey during a virtual program hosted by Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel.

“Tehran Children” is as much a personal journey as it is a travel narrative and work of historical nonfiction, as Dekel travels in the footsteps of her father and a quarter of a million Holocaust refugees who escaped to the former Soviet Union and the Middle East. What did they recall about these regions? And how are they being remembered in countries ranging from Uzbekistan to Iran?

Hannan and his younger sister arrived in Iran without their parents, who remained in Uzbekistan. They were greeted in Bandar Pahlavi by many members of Iranian’s 2,700-year-old Jewish community, who arrived with hugs and sweets. But the initial warm welcome by the country’s population turned bitter the following winter, when, amid low supplies, Polish refugees were seen as “parasites,” and graffiti in Tehran read, “all of Persia is hungry as it watches the Poles and the British eat its bread.” Concerned over an uprising, the British decided to ship the Polish Catholic refugees to India, Africa and New Zealand, and some 861 Polish Jewish children, including Dekel’s father, to British Palestine.

“Many ask why the story of these survivors of the East — those who survived in Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, etc. — is virtually unknown, especially since it is the story of nearly quarter million survivors,” Dekel told the Journal. That question, coupled with her father’s personal experience (which he never shared in detail with her), prompted Dekel to spend years researching the facts and many primary sources, such as diaries and letters of children and adults who were brought to Iran from Poland.

For Dekel, researching and writing “Tehran Children” was cathartic as a daughter and as a Jew: “My father was a complex parent: devoted, yet tense, aloof and at times inexplicably angry,” she said. “The research and writing of the book gave me a key to who he was. I now know exactly what he went through and who he was before the war. That’s liberating.”

The book also freed Dekel from a seemingly all-or-nothing relationship with the Holocaust: “On a more general level, as a Jew, I was always overwhelmed by the enormity of the Holocaust, so overwhelmed that I oftentimes avoided reading about it,” she said. “Knowing the specifics of this particular Holocaust experience, as painful as it is, feels liberating. It isn’t just this huge, shapeless horrific experience. It is a specific story set in time and place. I can cry, but I am no longer overwhelmed.”

From April to August 1942, 730 Polish Jewish children arrived in Iran and lived in tents on the former military barracks of the Iranian Air Force. Soon thereafter, over a hundred more children arrived, and the camp became known as the “Tehran Home for Jewish Children.” It was supported by the local Jewish community as well as many international Jewish organizations, such as the Hadassah Women’s Zionist Organization and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. These Polish Jewish youth became collectively known as the “Tehran Children.”

Rafael Szaffar, the only representative of the Jewish Agency for Palestine (founded in 1929), joined the 75-member Polish delegation that welcomed Polish refugees in Bandar Pahlavi. Before the war, Szaffar had immigrated from Poland to Palestine and was sent to Tehran to secretly help Polish Jewish refugees and orchestrate their eventual arrival in Palestine. The refugees, Szaffar reported, were “swollen from starvation, dressed in rags,” and looked “much worse than the Poles.” The Jewish Agency helped relocate some 870 “Tehran Children” to moshavim (cooperative farming villages) and kibbutzim (collective farms) in then-British-controlled Palestine, but their journey was unimaginable.

In January 1943, over 700 Jewish children arrived by truck to the Persian Gulf city of Bandar Shahpour; they boarded a freighter to Karachi, Pakistan, then traveled around the Arabian Peninsula through the Red Sea to the Suez in Egypt. They crossed the Sinai Mountains by train and finally came to the Atlit refugee camp in northern Palestine. In August 1943, over 100 children arrived in Palestine via Iraq. All of the children were resettled by the Jewish population in then-Palestine, known as the Yishuv.

Several years later, during Israel’s War of Independence, 35 of those “Tehran Children” died as civilians or soldiers (Israel lost one percent of its population in the war).

There’s a reason why many Israelis know about these children, whereas American Jews have little to no knowledge of them: “The Tehran Children became Israelis,” Dekel said. “They were absorbed into the new nation and shed their Holocaust refugee status very quickly. It’s only in the past decade or so that they began to be commemorated in Israel. And as far as research goes, there is a lot about the last leg of their journey — the travel from Iran to Palestine — but less so on what happened before that. That is where my book comes in.”

Dekel, who moved to the United States in 1993, currently knows about the existence of two “Tehran Children” in New York. She believes that a few hundred remain in Israel, although most have died (one passed away from COVID-19 last year).

Dekel’s important book questions who gets to be recognized as a survivor. “In truth,” Dekel said, “the most important question my book raises is: Why haven’t these quarter million Polish Jews who survived in the USSR and Middle East been recognized as survivors? Until now, these people have not been commemorated. They were also not included in reparations agreements with Germany.”

Dekel’s important book questions who gets to be recognized as a survivor.

Today, most Iranians know that there were Polish refugees in Iran during World War Two, but they do not know there were Jews among them. Dekel believes that they should be educated about this fact, and hopes her book will help achieve this task. She believes that Iranian leaders may know about the book and hopes it will be translated into Persian and read by Iranians inside Iran.

Dekel’s story gets even more complicated given Iran’s once cozy relations with Nazi Germany: During World War Two, Iran, under Reza Shah, pushed back against British and Russian pressure and sold oil to the Nazis. Iranians who were sympathetic to the Nazis drew comparisons between “Aryan Persia” and “Germanic Europe,” hoping to ally Iran further with the Third Reich. In 1933, pro-Nazi Iranian intellectuals in Iran established an overtly racist magazine called Iran-e Bastan (The Ancient Iran). In 1935, the country formally changed names from “Persia” to “Iran” (from the internal nickname, “Aryānām,” or “Land of the Aryans”). Nazis even exempted Iranians (except Iranian Jews) from the infamous Nuremberg Racial Laws, claiming they were actual Aryans.

But the saga of the “Tehran Children” marked the beginning of ties between the Jews of Palestine and those from Iran — ties that were further deepened after Israel was established in 1948. In the 1960s and 1970s, Iran had good de-facto relations with Israel, and many Israelis, especially architects and builders, lived and worked in Tehran and other major Iranian cities.

“I strongly believe that those ties could and should resume,” Dekel said. “The Israeli and Iranian people, and especially the young people, are natural allies.”

As for Jews worldwide, Dekel hopes “to convey the fact that Jewish groups around the world are interconnected and bear a mutual responsibility. Polish Jews, Iranian Jews, Iraqi Jews, German Jews who were refugees in Iran, the Jews of Palestine, American Jews, Bukharian Jews and other Jewish communities in Montreal, London, Mexico and Argentina are all linked in the book.” Indeed, her 2019 New York Daily News story, which powerfully retraced her father’s Yom Kippur experience as a child refugee in Iran, shows the undeniable interconnectedness of the Jewish experience.

“Many descendants have reached out to me in the wake of the book,” Dekel said. “Many of them knew nothing about this and the book enables them to fill in the missing pieces about their parents’ or grandparents’ past.”

In the decades immediately following the Holocaust, some Polish refugees to decided to stay in the country, marrying Iranian citizens and raising children. But nearly three thousand Polish refugees perished months after arriving in Iran. In their desperate starvation, many overate and suffered from acute dysentery. Others died from malaria, typhus and respiratory illnesses. The largest refugee burial site in Iran is a Polish cemetery in Iran that has 1,937 graves.

A separate area was reserved for Polish Jews and belongs to Tehran’s Jewish community. On each of those 56 graves is a Star of David and a name…in Polish.

Mikhal Dekel will speak virtually as part of Sephardic Temple’s Distinguished Speaker Series on March 17 at 6:30 p.m. More information may be found here.

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker and activist. Follow her on Twitter @RefaelTabby

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.