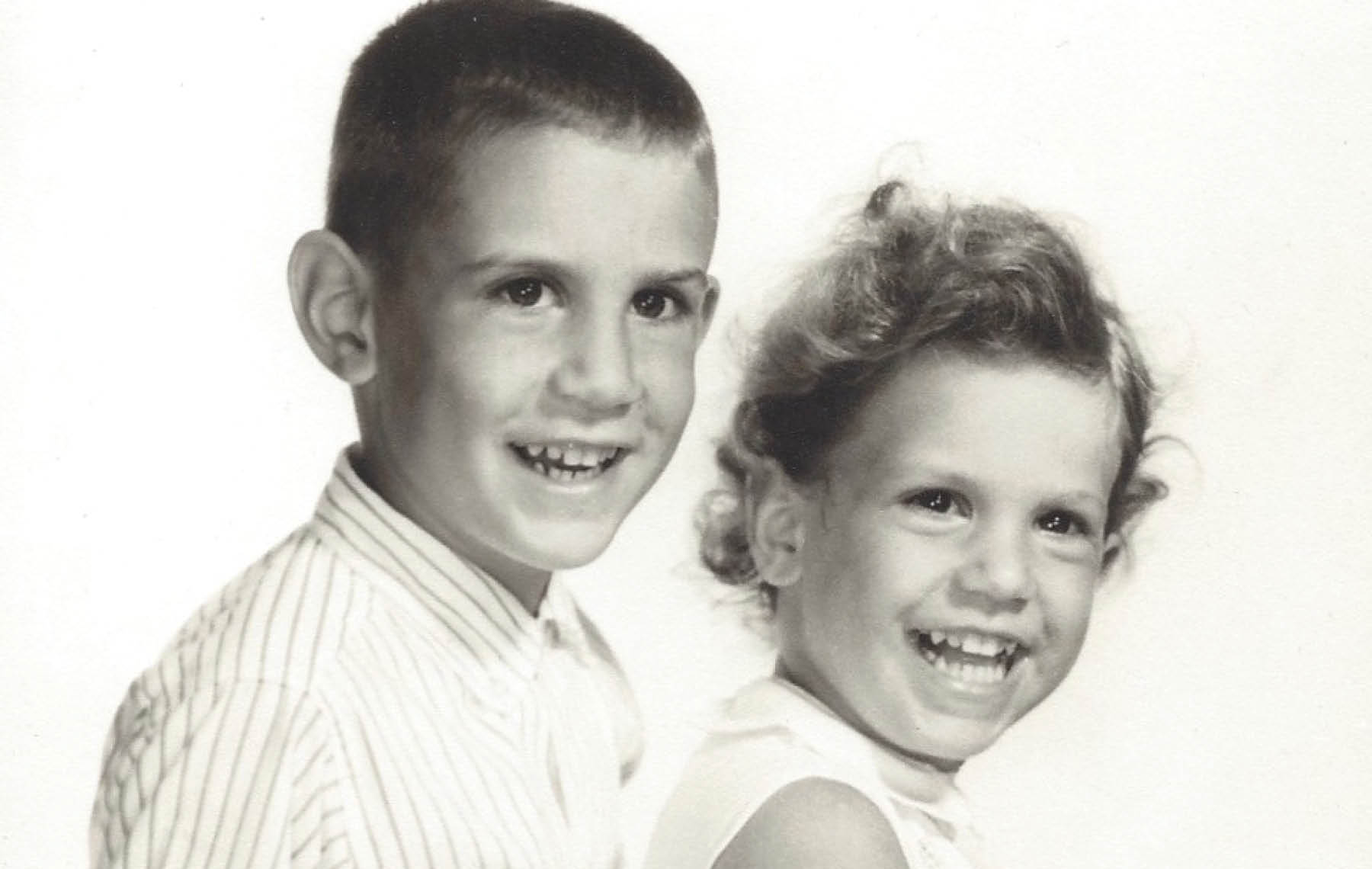

Peter and Susan Himmelman as children.

Photo courtesy of Peter Himmelman

Peter and Susan Himmelman as children.

Photo courtesy of Peter Himmelman My sister Susie, her husband, Peter, and two of their kids had been driving home from Camp Ramah in 2002 in their Toyota minivan. It was visitor’s day up in scenic Conover, Wis.; they’d driven up to see Michelle, Susie’s oldest. I don’t know what went on at camp that afternoon. I never asked. Maybe some skit with a Jewish theme, someone playing a guitar, the sound of young people singing Oasis covers accompanied by an acoustic guitar near a lake. … I don’t know exactly what happened at the site of the accident either. Here’s what I see in my mind’s eye based on what little I was told:

An elderly woman driving a Cadillac down a two lane highway, trees on either side; a “Barney” DVD playing in the minivan, Christian radio in the Caddy. The woman’s eyelids slowly slipping down over tired, old eyes, a dream of a firstborn son from long ago, hands letting go of the wheel, slipping to knees covered by a rayon dress from Walmart, and then an awful crash.

Susie had spoken some words to Peter and her girls from the overturned minivan before she died. Perhaps she said goodbye, I’m not sure. I never asked. Susie was trapped in the wreckage as the rest of her family was taken to a nearby hospital and treated for injuries. Susie had bled too much internally before first responders could extricate her with the Jaws of Life.

Somehow, I always knew she’d be the first of my siblings to die. I used to think it would be breast cancer. I used to imagine all of us suffering — her suffering, just like we did with my dad. Susie was never strongly rooted in the world. I don’t say this as a criticism of her; it’s not a comment about weakness, not at all. She wasn’t the least bit weak. You see, if there were a criticism, I’d direct it toward God. He didn’t make her well enough. You could see right through Susie’s skin. It was like the animal part of her, the very stuff of her was too thin. It was like the shock of suddenly seeing naked flesh through a tear in a blouse — that’s how easily you could see her spirit. She seemed vulnerable too, like something more than human, or something too kind to be human. Like I said, I don’t think God made her very well.

My brother Paul and my mom saw Susie covered with blood on a gurney in the hospital. She was DOA. I don’t know what else they saw. I never asked. By the way, if you ever accidentally kill someone in a car accident, I suggest you study this letter we got from the woman responsible for Susie’s death. It’s good.

“I cannot find adequate words to express my sorrow for the loss of your mother. We lost our youngest son Vernon at the age of seventeen shortly before his high school graduation in a gun accident. I only share this with you to let you know that I have some idea of the horrible pain and loss you are going through.

“I wish your mother’s life would have been spared and mine taken instead. I live with that anguish every day. I would never intentionally hurt anyone. I simply do not know what happened the day of the accident. I will continue to ask for God’s forgiveness and ask him to watch over you and your family.

“I pray that only good things happen to you. I hope that someday you will find it in your heart to forgive me. I’m truly sorry for your loss and pain.”

There are already plates of food piling up on the counter in my mom’s kitchen before the funeral. They hold mostly these items:

Bagels, lox, dill pickles, Spanish olives stuffed with pimentos, pickled herring, whitefish, gefilte fish, red and white horseradish, red onions, cut fruit, rye bread, blintzes, banana bread (some with chocolate chips, some with walnuts) and several kinds of cream cheese.

What strikes me as odd is how these foods, present in every Ashkenazic Jewish house of mourning, are the same foods (down to the Spanish olives and the whitefish) that you’ll find at every joyous celebration, every bris and every baby naming. They are neither foods of joy nor of sorrow but ethnic foods that declare, at times of profound change, that we are a people connected to a tradition and a past. We are the people of the unwavering Rock — the Rock of Israel and neither the deepest tragedy nor the most intoxicating happiness can wrest us from our past or our destiny.

Some friends of mine come to sit with me, and I don’t feel particularly sad. It’s as if the ‘I’ of me has gone away.

I put three pieces of gefilte fish on a paper plate, slather them in blood red horseradish and wolf them down.

A sign reads: “CAUTION! Refrigeration Room. There are chemicals present which are known to the state of Minnesota to cause birth defects.”

I’m sitting on a musty couch in the basement of Hodroff & Sons Mortuary listening to the low growl of the massive refrigerator’s compressor switching on and off. A month from today, my younger sister Susie would be turning 41 had she not died three days ago. I’m reading psalms as tradition dictates, within feet of her body as it cools behind a huge metal door. Some friends of mine come to sit with me, and I don’t feel particularly sad. It’s as if the ‘I’ of me has gone away. The person with my face and my name, the person sitting in for me will talk and make some wry comments until I return.

After an hour or so, my friends leave and I feel an urgent sense of obligation, a need to clean something or serve food to someone. But no one’s here; it’s just me, Susie’s body, and that hovering spirit of hers that used to peek out from her too-thin skin. I feel like I should open the metal door and sit in the cold beside her corpse, maybe hold her hand, speak some soothing words but I’m afraid, afraid to sit next to the dead. Afraid to see and to confirm what needs no confirmation. Instead, I sit on the couch bemoaning both my loss and my lack of bravery.

The next morning at the funeral, I can’t cry. I float through the service at a remove, watching as Susie’s daughters, bruised and bandaged from the accident, are led into a black Lincoln and driven to the cemetery. At Susie’s open grave, the bereaved are enjoined to complete the burial ritual by shoveling dirt on the casket. It’s a mitzvah and it’s better than letting the cemetery workers finish the job with just a few clattering scoopfuls from the Caterpillar earth mover.

It’s my turn to take the shovel and, although I haven’t slept in days, I feel suddenly strong. I climb to the top of the dirt pile, kick the blade of the shovel with my boot heel and drop the dry soil over the top of the casket. I can hear birds taking to flight over the crosstown highway and I feel the sun on my neck and shoulders.

I imagine I am covering my sister with a warm blanket, tucking her into bed one last time, as though this final act might atone for all the times I failed her.

And finally, I start to sob. The tears, which hadn’t come until now, are precious to me. I listen to the thump of each rocky clod of earth as they land on her casket. I think about rhythm and drums, history, and the missing face of God. I feel unfettered, mystic. I am light and my movements are exquisitely primitive.

Suddenly, as I’m shoveling, a hand gently touches my shoulder. It’s the rabbi from Congregation Beth Emet, and loud enough for everyone to hear, he stage-whispers, “Peter, why don’t you give someone else a chance?” It’s a solemn moment and yet, I can’t help wanting to raise the shovel high above my head and come down hard with the blunt edge on the rabbi’s neck. Instead, I step away from the grave and give the shovel to another mourner.

There are people who have been made wise through grief and time. They learned through their painful lessons, the value of silence. For others, the allure of a performance is just too powerful. I look back at the rabbi from Temple Beth Emet and smile as I see him, away off in the distance. But now, out among the throng of mourners, I see my mother’s best friend, Carolyn. Carolyn is one of the wisest people I know. Her husband, Burton, died a few years ago and immediately after his funeral, at the shivah house to be precise, her 25-year-old son, Marty, dropped dead of a brain aneurism.

My mom got a call from Carolyn the day it happened. “Beverly,” she said, “Martin died.” “No, Carolyn, my mom said with real solemnity and real pity, “Marty didn’t die, it was Burton.” But my mom was wrong, Marty did die, on the day of his own father’s funeral. Trust me, this woman, Carolyn, has mastered the art of being there without ever having to say a word.

Two months after Susie’s funeral, I’m back in Minneapolis and I’m sitting with my mother in her kitchen. She tells me there’s a dead muskrat in the pond at the edge of her lawn. “What should I do?” she asks.

I walk down to the pond as she waits inside. From a distance, the pond looks like a putting green, the algae so thick it’s become a carpet on the surface of the water from too much fertilizer sluicing off the lawns encircling the faux lakefront. Just under a sweeping elm, I see what at first looked like a large gray-black stone. It turns out to be a muskrat that had died face down in the shallow water. All that is exposed is its huge, smooth backside.

Normally, I don’t do muskrat removal. Normally, I’d call a professional but things are far from normal. As I look back from the pond at my mother standing in front of a large picture window, two troubling questions arise: Exactly what is the essential difference between me and the guys you call to haul away the stinking carcass of a rotting muskrat, and why is it assumed that I’d have to call on one of them to do the job? Maybe, it’s my mother’s intense sadness or maybe it was having recently been in Israel (where Jewish men aren’t entirely feminized) that compels me to march back through the evergreen hedges, back through the yard to grab a three-pronged hoe and a snow shovel off the pegboard on the wall of her garage.

At the pond, I don’t flinch as the hoe bites into the rib cage of the muskrat with a dull watery sound. I drag the bulk of it and the entrails that have mixed with the gurgling algae toward me. Then I lift the entire mess with the snow shovel into a double-thick garbage bag. I’m struck by how truly free of sin I feel at just the moment I twist the top shut with the red cord. I see my mother. She’s standing in her living room. Standing alone. Watching me from her large picture window.

Susie’s car crash wasn’t my first encounter with death. It was however, another jarring reminder of this stark — yet hardly noticed fact — we are here, and then we are gone.

Yisgadol v’yitkadosh …

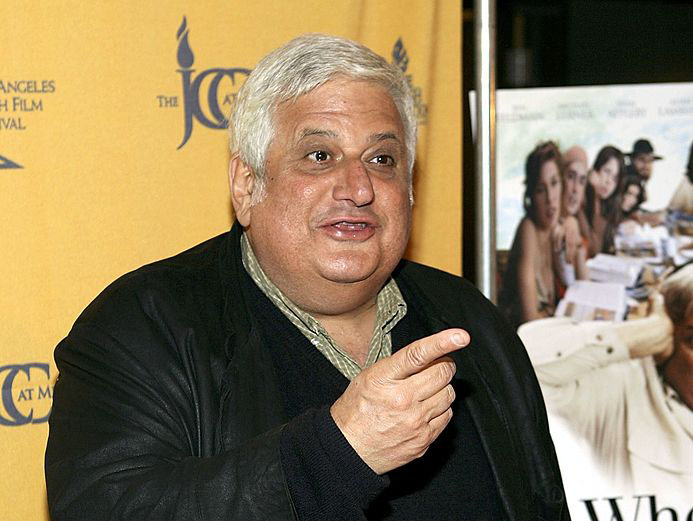

Peter Himmelman is a Grammy- and Emmy-nominated singer-songwriter and rock ‘n’ roll performer. He is also the founder of Big Muse, a company that helps organizations leverage the power of their people’s innate creativity.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.