Andy Warhol

Two Marilyns, 1962

Andy Warhol

Two Marilyns, 1962 The Jewish Museum is somewhat of an institution in New York City. Housed in the elegant 1908 Warburg mansion, the museum is known for innovative exhibitions of Jewish artists, attracting visitors of all ages. It is, in fact, the first Jewish museum in the United States.

In the early 1960s the Jewish Museum helped to make NYC — and the United States — the epicenter of modern art.

What isn’t well known is that in the early 1960s the Jewish Museum helped to make NYC — and the United States — the epicenter of modern art.

But a new exhibition, up at the museum through January, will change that. “New York: 1962-1964” explores the pivotal three-year period in the history of art and culture when the Jewish Museum transformed itself into one of the most important cultural hubs in NYC.

Untitled, 1959

Alan Solomon became the director of the museum in July 1962. He immediately began organizing ambitious exhibitions dedicated to what he called the “New Art,” work that was being made by an emerging generation of artists who sourced their material directly from everyday life — things that were “familiar, public, and often disquieting,” according to the exhibition’s wall text. New Art, according to Solomon, showed “the intricacy, the ambiguity, and the indeterminacy of experience” in a rapidly changing city.

Solomon’s groundbreaking exhibitions, including the first-ever retrospectives of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, established the Jewish Museum as a site of radical experimentation, and helped to establish New York City as the global capital of the art world. In 1964, on a commission from the U.S. government, Solomon took a group of young American artists to the Venice Biennale, with Rauschenberg becoming the first American to win the grand prize in painting.

The current exhibition, installed across two full floors, is filled with 180 works — painting, sculpture, photography, film, fashion, design, dance, poetry — from this pivotal three-year period. Artists featured include Merce Cunningham, Jim Dine, Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, Agnes Martin, and Andy Warhol. Solomon chose artists who reflected the “rawness and disorder of the metropolitan scene.”

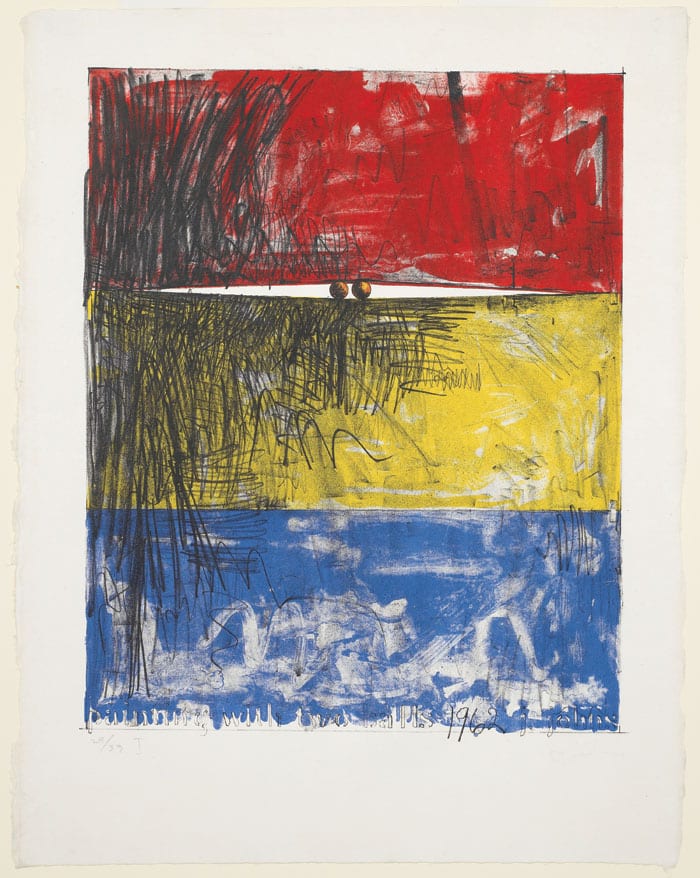

Painting with Two Balls I, 1962

The design of the exhibition, by Selldorf Architects, also features material from pop culture: newspapers, magazines, books, film, television clips on period TVs, as well as a jukebox playing ‘60s music. All of which creates a layered portrait of the largest and most diverse city in the U.S. at the time.

The exhibition also documents the profound social changes the artists were responding to, from the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (1963) to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1963) to the passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964).

According to the exhibition’s gorgeously designed catalogue, there was a surge of public interest in art during the early 60s. So along with these innovative artists came the Jewish gallerists who represented them. Indeed, the Jewish Museum provided a home for many Jewish dealers and collectors who later became influential in the city and across the country.

Walking through the dynamic exhibition, I was struck by the fact that, with notable exceptions (for instance, dance stills from the NYC Ballet), few of the works would fall under what I would consider “beautiful.” In fact, the contrast between most of the work and the gorgeous interior architecture is quite stark. But beauty wasn’t the point. It was a rebellious period, and the artists were pushing boundaries, responding to their rapidly changing world.

None of the art was overtly political. Rebellious and politicized are two very different concepts.

But here’s an important distinction: none of the art was overtly political. Rebellious and politicized are two very different concepts. The music of the early ‘60s, from Bob Dylan to the Beatles, was also rebellious but not overtly politicized. In this sense, art serves a historical purpose. But it’s a distinction that’s been lost in recent decades, when overtly politicized “art” has come into vogue.

The exhibition also shows photos of the truly peaceful protests of the time, as well as people out in the streets creating art. The photos also document the changing realities. A photo by Bruce Davidson in 1962 shows a black woman and white woman sitting next to each other at a lunch counter.

All of which led me to a question. We’ve been going through a revolution of sorts in the past few years — call it woke or leftist. Where’s the art and music to accompany it? There has been very little, and what has been produced is so overtly politicized one would have to call it propaganda, not art. Why is today’s social and cultural change so different from the ‘60s? My theory is that the social changes of the ‘60s were instinctual — natural — emanating from a true sense of justice.

Today’s ideological demands are not at all instinctive. In fact, many emanate from lies. As John Keats put it: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty.” Certainly beauty can’t be created from lies, but neither can rebellious art. True rebellion against injustice must be forged bravely through truth.

Perhaps that could be the subject of the Jewish Museum’s next extraordinary exhibition. ■

Karen Lehrman Bloch is editor-in-chief of White Rose Magazine.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.