One of the most electrifying moments in the Torah occurs when Joseph reveals himself. “He said to his brothers, ‘I am Joseph. Is my father still alive?’ But his brothers could not answer him because they were so frightened in his presence.” The Talmud tells us that Rabbi Elazar wept when he read this verse, saying “If the brothers were terrified when a man of flesh and blood revealed himself, how much more so when the Holy One, Blessed is He, reveals Himself.”

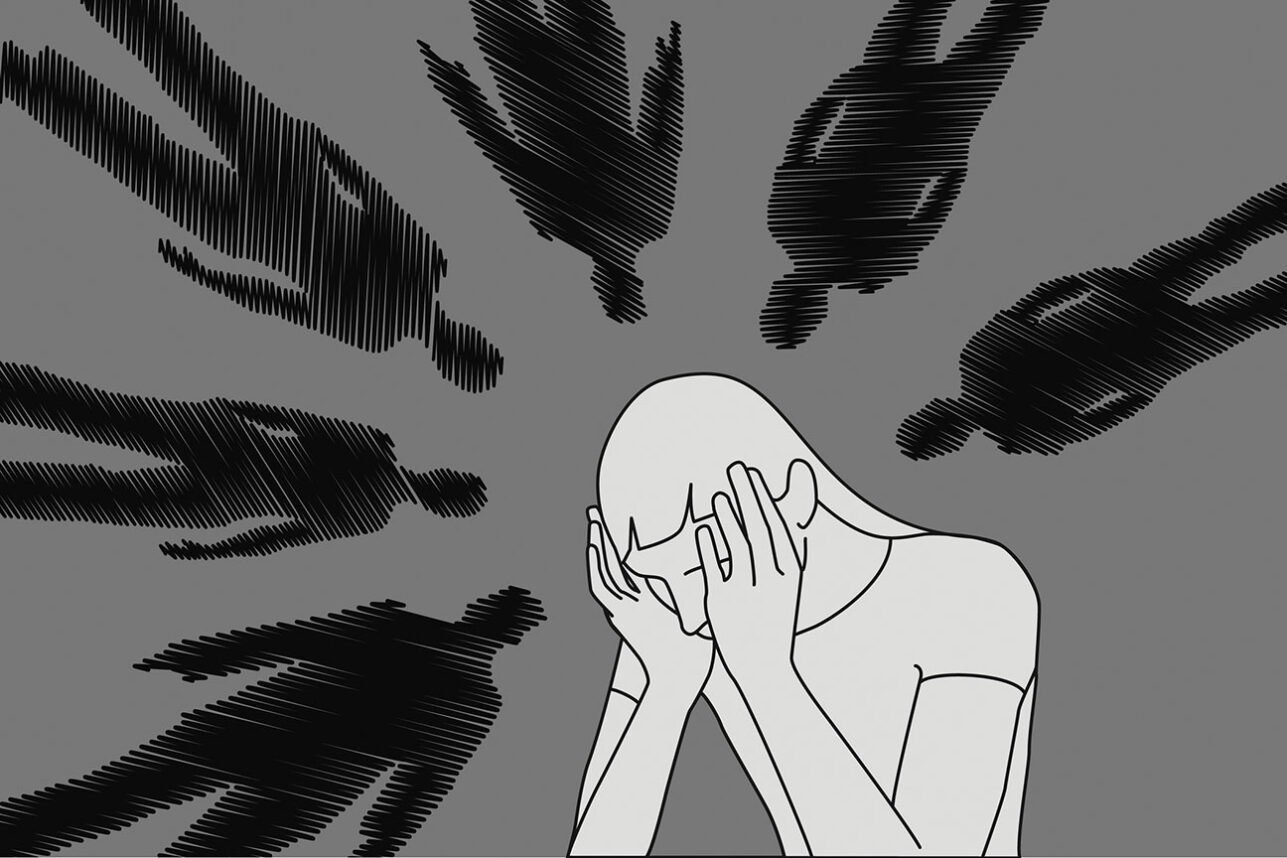

During the Days of Awe, the Holy One, Blessed is He, reveals Himself, and we are revealed to ourselves. The King is in the field. The poverty of our excuses and self-deceptions becomes obvious, undeniable. God draws very near. Whether we articulate it openly or not, we are frightened and ashamed in His presence. The seeming remoteness of His involvement in our day-to-day lives — the false comfort we take during the year that God is not seeing and hearing us — gives way during the Yamim Noraim to an overt awareness that our inscrutable King is here and is judging us.

During these fateful days, we acknowledge that truth with an honesty we either can’t muster or actively avoid during the rest of the year. For a short few inspired weeks, we understand, intellectually and emotionally, that we are passing before the Shepherd who counts us, assesses us, and calls to us by name. We know we can’t hide so we say, inwardly and silently to ourselves “Hineni, yes, I am here,” but we have no confidence in what we would say back to God. What confidence can we have in another reckoning as to who we really are? How should we react — flawed human beings so disappointed and frustrated with ourselves — when we contemplate that God is within us, beside us, evaluating us?

By any logic, as Rabbi Elazar says, we should be appalled, like our brethren in the palace of Pharoah, when our callousness, neglect, and false sense of virtue are suddenly exposed. We should be demoralized by the meager — if any — progress, we make in improving and refining ourselves. We should be discomfited by the litany of unfulfilled promises and commitments we accumulate year after year. If we were honest, we would weep — like Rabbi Elazar — when we reflect on how we waste what God has given us in this life, starting with time, the most precious gift of all.

When Joseph revealed himself to his brothers, they were too paralyzed to act, too ashamed to speak. So Joseph acted and spoke for them. He came close to them and wept with them in a mystical reunion borne of the intense familial love that unites every Jew across all generations. Joseph spoke words of comfort and encouragement, he reassured his brothers that they could trust one other, and he predicted a future of unity and blessing. And Joseph made plans for their father Jacob – our father Jacob – to join them in exile, to guide them, and to bless them.

And so it is for us. The Holy One, Blessed is He, has revealed Himself to us, and we are revealed to ourselves, and we don’t know what to do or say. But we know, in our most essential being, that our Parent made us, loves us, and understands us. And so, through our tears, we ask Him to act for us and speak for us. And He does. Day by day, our feelings of inadequacy and shame begin to transform over the Yamim Noraim, as God embraces us, comforts us and reminds us that nothing can sever the love that binds us together. Over these inspired days, we feel the divinity within us, the transcendent spark unbound by place or time. We sense God’s wordless encouragement, His reassurance that we can be trusted, that the coming year will be one of great promise, that we have what is required to do better. And that He will be with us to guide and bless each of us — a soul stuck awkwardly in a vulnerable body — as we navigate an exile we don’t understand.

When we are revealed to ourselves, our initial, legitimate reactions — fear, paralysis, fatalism — give way to a profound, powerful consciousness of reconciliation, love, forgiveness and optimism.

During the ten days of self-examination from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur — the aseret yamei teshuvah — we experience that catharsis and reorientation. We learn that when the Holy One, Blessed is He, reveals Himself, and when we are revealed to ourselves, our initial, legitimate reactions — fear, paralysis, fatalism — give way to a profound, powerful consciousness of reconciliation, love, forgiveness and optimism. We come out of Yom Kippur exhausted, exhilarated and yearning to move from the ethereal to the practical. We will take what we have learned and build a house for our God so we can be with Him a little while longer, before this holy time slips away from us yet again.

And when we sit in the sukkah, our King, our Parent, our Teacher, our Friend, is there as well, within us, beside us. As we move around the sukkah, having conversations with family and friends, eating our meals, our soul wordlessly, continuously conveys the intensity of our gratitude for this temporary, fragile place in time, for this short, tenuous life in a broken and beloved world. Our soul silently exudes ecstatic thanks for those whom we love and have loved without any measure. Our soul cries out that our humble sukkot are nothing less than our forefathers’ sukkot in the wilderness where, come what may, the Ancient of Days took care of us, protected us and guided us.

And when Sukkot — the season of our greatest joy — inevitably ends, our soul reminds the King, crying as we part, that despite our idolatry, ingratitude and failures, His cloud of glory returned to us in that exile of old when we so desperately feared that it might not. That He has promised to return to us forever though we fear He will not. That whenever He reveals Himself to us, and we are revealed to ourselves, it is so that we can be forgiven, and that we can begin again.

Pierre Gentin lives in Westchester County, New York.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.