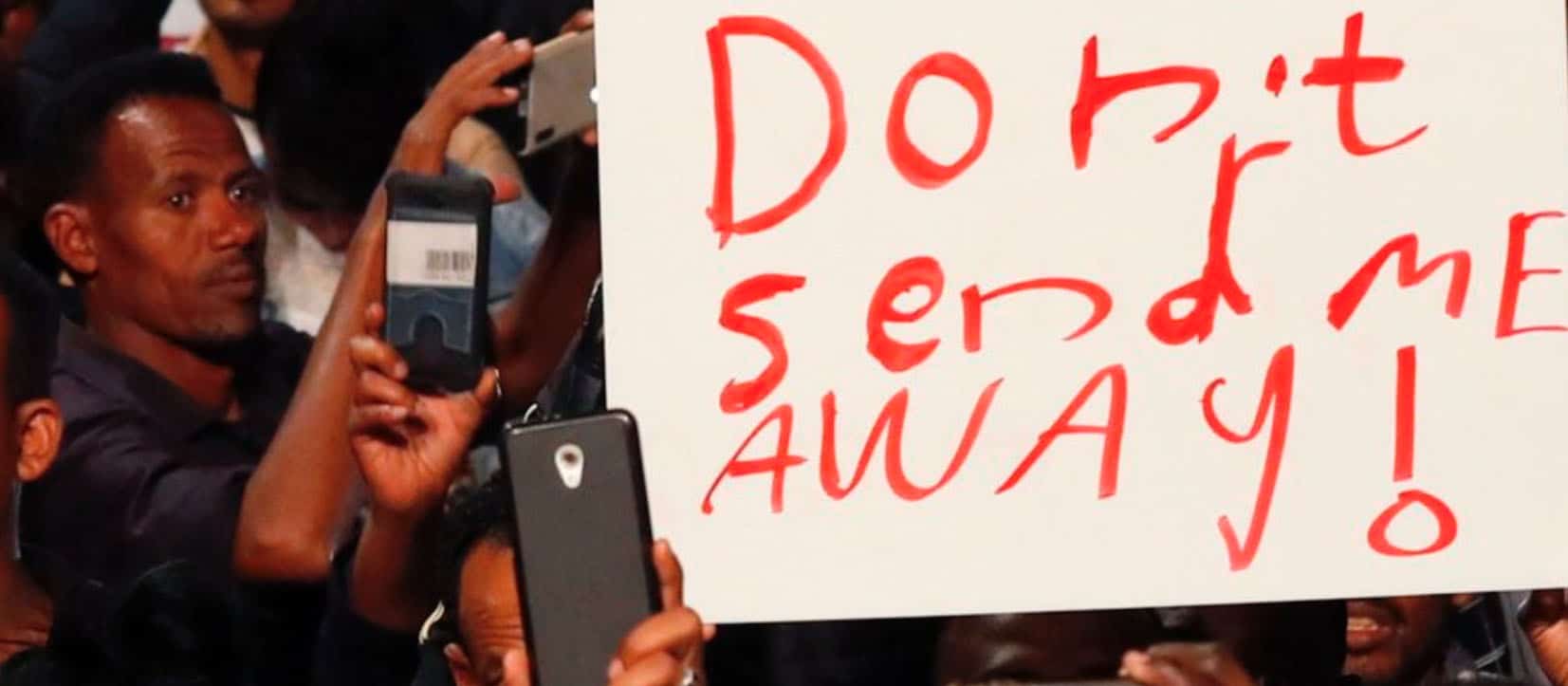

THE MEDIA LINE — As news spread Friday evening that Israel and Sudan would establish diplomatic relations, concern swept the Sudanese community in the Jewish state.

Their already uncertain fate – many entered the country illegally to seek refugee status or asylum – is now even more up in the air, with fears of deportation back to hot spots of genocide in Darfur, the Blue Nile region and the Nuba mountains.

“Safe is not a word I would use for Sudan,” Shira Abbo, spokesperson for Hotline for Refugees and Migrants, a Tel Aviv-based non-profit, tells The Media Line.

“There are attacks against refugees and displaced people returning to Sudan as they attempt to reclaim their land,” she says.

Usumain Baraka is a refugee activist from Darfur who has been living in Israel since 2008.

“People are saying that one of the first steps of peace is to deport Sudanese living in Israel back to Sudan,” he tells The Media Line. “[But] the situation there is the same as before. People are dying every day. The war and genocide continue. For us, going back is not an option.”

Baraka, who lost his father and older brother in a genocide that started in 2003, went to live in a United Nations-supported camp in Chad together with his mother, two sisters and a brother. In 2007, he and his mother began contemplating his life options: go back to Darfur to fight with rebel groups or make a life elsewhere and obtain an education.

According to Baraka, his mother told him to seek the normalcy and education he craved.

“Learn how to stop genocide without killing people,” she added.

“I was 13 years old and I didn’t fully understand what she wanted from me,” he says.

He eventually understood, and her words inspired a harrowing journey from Chad to Libya to Cairo, where he saw a television program about Jewish history. In it, an Israeli man explained how it took 40 years for the biblical Israelites to reach the Promised Land.

The man on TV also spoke about the Holocaust, something Baraka had never heard of but to which he felt an immediate connection.

The program spurred him and a friend to head to Israel, taking what he calls the “difficult way.”

A Bedouin guide dropped them in the Sinai, 25 miles from the Israeli border, because they lacked the money to go farther. They escaped gunfire from Egyptian soldiers before being rounded up by Israeli troops, who put them in a holding compound in the Negev.

A month and a half later, Baraka found himself in Beersheba, where he knew no one. Eventually, he was accepted to a religious boarding school, after which he earned both undergraduate and Masters degrees from the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya.

Now he is worried that he will end up like friends of his who had reached Israel from South Sudan.

“I am scared, because… Israel deported South Sudanese back to South Sudan, where many lost their lives,” he says. “Some people who were lucky ran away to neighboring countries like Kenya and Uganda, where they started a new refugee journey.”

Baraka tells of hearing from relatives living in Sudanese camps.

“They confirm that it is still dangerous, especially for people like me who were activists against the government,” he states.

On numerous occasions, Israel has tried to deport Sudanese and other African nationals who are in the country illegally.

“These people have been in Israel for [some] 10 years, and at the beginning, the country denied them access to the asylum system,” Abbo relates, adding that applications for asylum began being accepted only in 2013.

“The simple reason for this is even Israel’s broken asylum system knows that people fleeing genocide are refugees,” she adds.

Baraka wants ties between Israel and Sudan that will eventually extend to diplomatic relations – but only when Khartoum stops the genocide.

“My dream is normalization between the two countries, but they [the Israelis] have to know when, with whom and how to do it,” he says.

Monim Haroon came to Israel in 2012 after fleeing Darfur over his criticism of the Sudanese government. He was held in a detention center before being released. He was eventually granted asylum in December 2017.

Haroon describes as “complicated” the feelings of Sudanese nationals toward possible ties between Israel and Sudan.

“I was one of the student activists calling for normalization between Israel and Sudan when I was in Sudan, and to see this happening is a historic step. [But] some are worried because of the [Israeli] government’s [apparent] intent to deport asylum seekers,” he tells The Media Line.

“I think it will be very hard for Israel to file orders to deport us from Israel,” he continues.

“First, there is no change… regarding the reasons that led us to flee our country and become refugees in Israel. Second, normalization doesn’t mean deportation,” he says.

“There are Sudanese in England and other European countries that have diplomatic relations with Sudan, but they are still considered asylum seekers,” he notes.

Haroon believes the Israeli government now has an important role to play in ending the ethnic violence in his home country.

“What we are trying to tell Israeli society and the government is [the refugees] are a result of terrible policies by the Sudanese government against us and our families,” he says.

“We went through genocide, ethnic cleansing [and] mass rapes of our sisters and mothers,” he goes on.

“We want [Israel] to understand that this is what is [still] happening in the Blue Nile, the Nuba Mountains and Darfur, and we want [it] to help us stop this tragedy,” he says.

He notes that this would be in Israel’s own interest.

“Once the genocide is stopped,” Haroon says, “people will voluntarily return to Sudan.”