Jonathan Porath, “Here We Are All Jews: 175 Russian-Jewish Journeys” (Jerusalem, New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2022).

There once was a time when Jewish activists traveled to the Soviet Union to meet with Soviet Jews, bringing them Jewish books, trinkets, Stars of David and, for the more religious, siddurim, chumashim, tallitot and tefillin. We even brought jeans and digital watches, which could be sold in the black market and could assist them financially. We met these Jews in subways and on street corners — sometimes deliberately, clandestinely, and at other times accidently. We visited their homes. We met older Jews who had retired in synagogues and younger Jews outside of the synagogues.

Any activist who had read Elie Wiesel’s groundbreaking work “The Jews of Silence,” where he described his encounter with Jews outside of the Arkhipova 9 Synagogue in Moscow on Simchat Torah, tried to get there for the “happening,” and once we got there, we met young Jews desperate to reconnect with the Jewish people, willing to risk their futures and their careers, to endanger their family and their freedom, to live as free Jews, even if only momentarily, in order to reaffirm their connection to the Jewish people.

We were their lifeline and their teachers — or so we thought. We soon learned that they were our teachers, our models, our heroes and our lifeline.

In their unfreedom, we came to understand the blessing of our freedom. For them to manifest their Jewishness took courage, daring and determination. For us, it took so little. For them it meant so much; for many of us, not enough. For them, Israel was a dream, the hope “to be a free people in our land, the land of Zion, Jerusalem.” For us, Israel was an imperfect reality, one of promise yet not without some disappointment. Seldom does reality fulfill the dream.

Soviet Jewry energized a whole generation of Jewish leaders.

It was a do-over for the failure of the earlier generation to save the Jews in the Shoah. The fight for Soviet Jewry energized school children who shared their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs with Soviet Jews their own age who were denied the opportunity to celebrate Jewishly their own coming of age. The struggle for Soviet Jewry motivated Jewish housewives who marched proudly for freedom; it gave Jewish students who were marching in Washington and in Selma for the freedom of Black people a means of replicating those marches for their own people. It garnered Jewish leadership, albeit after some skeptical delay: Men and women who were at the top of their professions and could use their talents and their political contacts to fight on behalf of their beleaguered brethren. It joined human rights activists with anti-Soviet hawks and Zionists, all motivated by a common mission: “Let my people go!”

It brought together Jews from throughout the United States, joining with Refusenik heroes and Israeli leaders in the largest Jewish march ever, to press for the Soviet Jews freedom in December 1986, on the eve of the summit between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev. Nothing of that magnitude had ever occurred in American Jewish history. Nothing of that scale has happened since.

It is not presumptuous to say that it was one of the factors that contributed to the demise of the Soviet Union. Activist Jews took a measure of pride in this unimaginable achievement.

So it was with anticipation that I began reading Jonathan Porath’s memoir of his many trips to the Soviet Union. Readers should be informed that his parents of blessed memory were my neighbors for several years when I lived in Washington. As I shlep dishes up from the basement each Passover, my wife reminds me that we were going to buy their home if it were ever for sale as it had a Passover kitchen. I knew Jonathan when he was a young rabbinical student and have admired his work during the past half century.

This book exceeded my every expectation.

Quite early in the movement, Porath traveled to the Soviet Union beginning in 1969, first as a personal journey and then as the leader of a United Synagogue Youth mission to the Soviet Union. Imagine for a moment: Parents were allowing their teenage children to travel as Jews deep beyond the Iron Curtain at a time of growing tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, before there was email or an iPhone, when such a trip required a cone of silence with the outside world, when such trips were dangerous and one could be harassed, even arrested. They visited synagogues and brought themselves — young free Jews who were Jewishly learned, religiously engaged — offering to those who imagined that they were the last Jews, the knowledge that the Jewish people would endure.

These were the heady years just after the Six Day War when Soviet Jews were bravely coming out of the closet as Jews and when many American Jews were taking the same steps with the full freedom to embrace their Jewishness.

He is a wonderful storyteller, describing these early trips in great detail, seemingly remembering everything, everyone, depicting the people they met, the places they visited and the intimate contact between Jews. “Et achai ani mefakesh,” “I am seeking my brethren,” they said one to another, and brethren, they were. These were the heady years just after the Six Day War when Soviet Jews were bravely coming out of the closet as Jews and when many American Jews were taking the same steps with the full freedom to embrace their Jewishness.

I made several such trips in the 1970s and the 1980s and I read of Porath’s encounters with a sense of familiarity. I knew those people; I was in those situations. I was inspired by them as were he and the teenage youth who came with him, some of whom — like the current Chief Rabbi of Poland — I know well. And for those for whom this is history rather than living memory, Porath writes beautifully. He will take you back to those precious and precarious moments in time.

But Porath kept returning again, again and again. He also traveled widely into the hinterland of Soviet Jewry, places far from Moscow, Leningrad, and Kyiv, into communities large and small, places where Jews had no community and no opportunity; places so far away that Jewish life was comparatively free.

After the demise of the Soviet Union, Porath was made an offer he could not refuse. He became an integral part of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s herculean work to rebuild Jewish life in Russia for those who chose to remain. The Jewish Agency sought to bring Jews to Israel, while the Joint Distribution Committee had a different mission — to sustain those Jews and recreate Jewish life for those who remained in Russia. They were community organizers, community creators. So instead of being a lifeline, he became a community builder, using his skills as an educator and rabbi, as well as his knowledge of Russia and Russian, to create, nurture and sustain Jewish life in Russia. He then enjoyed their first taste of freedom, their first experience of democracy. Later even as democracy gave way to autocracy, Jewish life still remained possible.

Read this book and enjoy one of the most important Jewish success stories of the 20th century. Read it and learn what Jews estranged to Jewish life, virtually severed from contact with the rest of the Jewish world, did to reunite with their brothers and sisters. It will give you faith in the eternity of the Jewish people, confidence that given the will, we can overcome significant obstacles and prevail. It will also give American Jewish readers a sense of gratitude for the freedoms we enjoy and the many opportunities that are available to us, which, far too often, we ignore.

One must be grateful to Porath for making this epoch in Jewish history come alive and for sharing his journeys with us. He so vividly portrays a time when Jews felt the inspiration and the power to achieve the seemingly impossible. He writes with fervor and passion — qualities I so admire in him, qualities too often I find missing today.

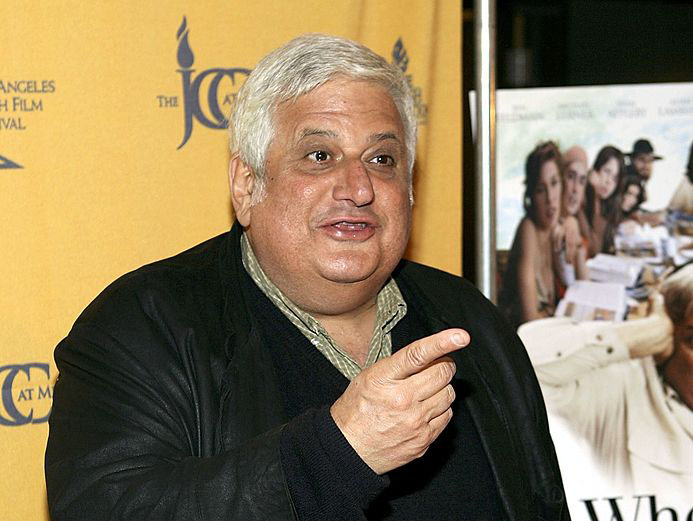

Michael Berenbaum is a Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies and Director of the Sigi Ziering Institute: Exploring the Ethical and Religious Implications of the Holocaust at American Jewish University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.