“To the making of many books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh” said Ecclesiastes [Kohelet in Hebrew], traditionally believed to be King Solomon, sometime before his death circa 931 BCE. “If that’s the case, here are three new commentaries on Ecclesiastes,” Koren Publishers said in 2023 CE.

David Curwin’s “Kohelet: A Map to Eden: An Intertextual Journey,” Erica Brown’s “Ecclesiastes and the Search for Meaning,” and Asael Abelman and Jonathan Grossman’s Hebrew language “Ecclesiastes: A Crack of Light” all offer different, and complementary, analyses of the notoriously morose and challenging book, read by many Jewish communities throughout the globe during the Shabbat of Sukkot.

David Curwin’s “Kohelet: A Map to Eden: An Intertextual Journey,” Erica Brown’s “Ecclesiastes and the Search for Meaning,” and Asael Abelman and Jonathan Grossman’s Hebrew language “Ecclesiastes: A Crack of Light” all offer different, and complementary, analyses of the notoriously morose and challenging book, read by many Jewish communities throughout the globe during the Shabbat of Sukkot.

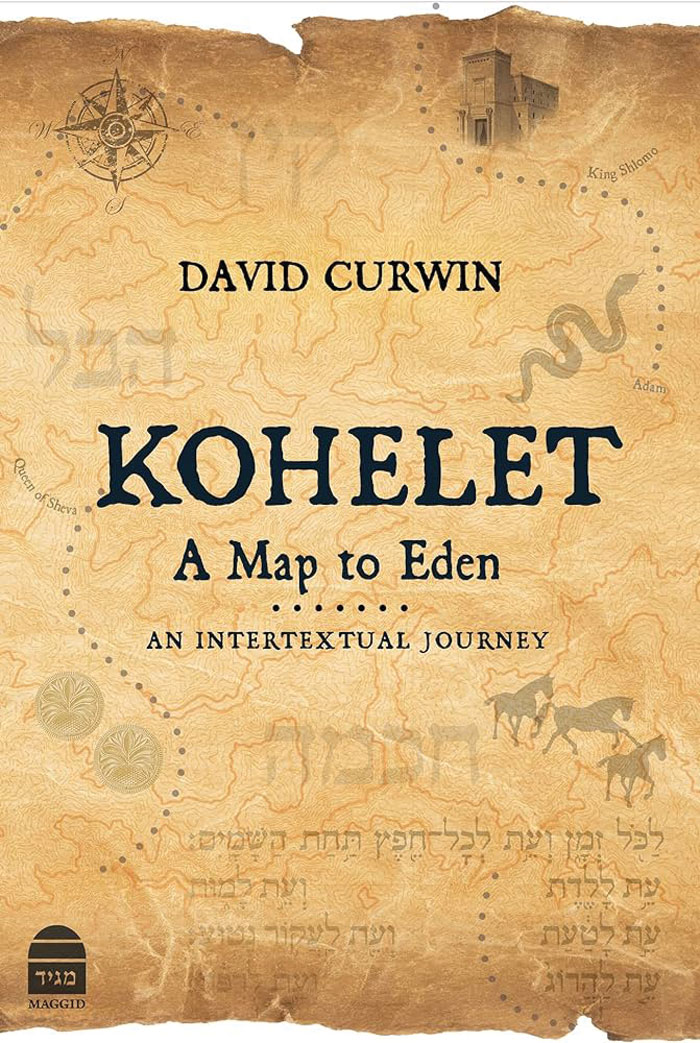

Curwin is an independent scholar who has published in Tradition and Jewish Bible Quarterly. His commentary is produced in conjunction with Rabbi David Fohrman’s Aleph Beta, a nonprofit media company that produces videos and books utilizing a literary approach to the Bible, and has the breezy, accessible tone that is the organization’s trademark. To Curwin, the key to understanding Kohelet lies in the very beginning — of the world, that is.

Stressing Ecclesiastes’ mournfully repeated lament that “all is hevel,” usually translated as “fleeting breath,” Curwin sees a callback to Abel [Hevel in Hebrew], the slain brother of Cain in the book of Genesis. As Curwin argues, “Kohelet can be read as Adam reflecting back on the tragedies of his life.” Thus Ecclesiastes 2:5’s “I made gardens and orchards for myself and planted them with every kind of fruit tree” is an allusion to the Garden of Eden, tilled by Adam. The eighth verse of chapter 10, “he who breaches a fence, a snake may bite him” references the snake who tempted Adam and Eve into tasting the forbidden fruit. And Kohelet’s morose observation that “Man [adam] has no power over the life-breath … no one rules on the day of death” is, as Curwin argues, Adam’s tragic admission that he “had no power over the life-breath; he could not save Hevel on the day of his death.”

In this reading, the book’s ending, “The final word: it has all been said. Fear God and keep His commandments! For this is the whole of man [adam]” is not, as modern scholars have suggested, a pious insertion by a later redactor uncomfortable with the author of Ecclesiastes’ seeming lack of faith and commitment to the commandments amidst his dozen chapters of cynical observations that the wise and wicked end up with the same deathly fate. Rather, it is an intra-biblical interpretation of the Cain and Abel story. As Curwin puts it: “Adam is looking back, saying if he had feared God and followed his commandments” not to eat from the tree of knowledge, the tragic downfall of his fratricidal sons would never have happened.

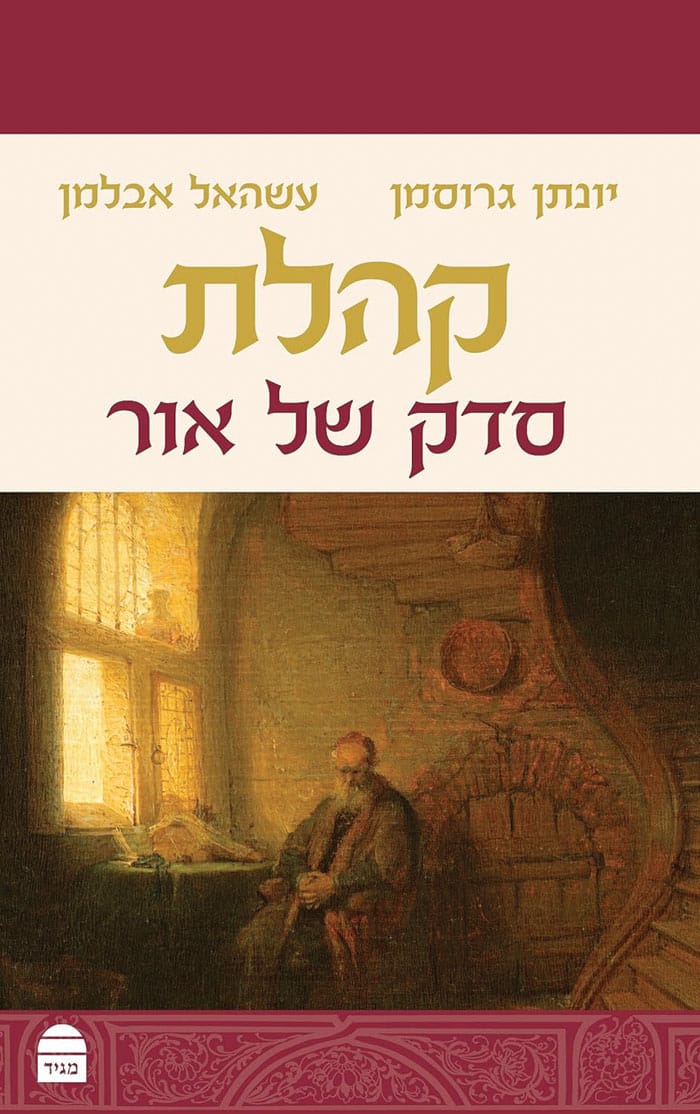

While Curwin focuses on Ecclesiastes’ ties to the tree of knowledge, Abelman of Shalem and Herzog colleges and Grossman of Bar-Ilan University focus on treatises of Wisdom. Both within the Hebrew Bible and in the corpus of ancient Near Eastern traditions, numerous texts, from Egyptian writings on Maat — perceived to be the order of harmony that governed the world — to Aristotle’s “Nicomachean Ethics,” to the Bible’s own Book of Proverbs with its aphorisms such as “Let the wise hear and increase in learning, and the one who understands obtain guidance” and “He who gathers in summer is a prudent son, but he who sleeps in harvest is a son who brings shame” claimed to explain the hidden rules for life under the heavens. The prudent would prosper. The morally just would merit justice in return.

To these polestars, Ecclesiastes says “feh!”

Rather, Solomon, speaking from experience, retorts, “I saw under the sun, in the place of justice, that wickedness was there; and in the place of righteousness, that wickedness was there.” “I praised the dead that are already dead more than the living that are yet alive.” “The fates of both men and beasts are the same: As one dies, so dies the other.”

Much of Ecclesiastes’ statements, in Abelman and Grossman’s view, are assembled teachings (Kohelet means “the Assembler”) swirling around the philosophical winds of his era. Some are cited because he liked them, others in order to disagree with them.

Deuteronomy’s urging to swiftly fulfill vows made to God is cited with approval. From the pagan myth of Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s friendship comes the gleaning “two are better than one … If either of them falls down, one can help the other up.” But to Proverbs’ offering “For wisdom shall enter into thy heart, and knowledge shall be pleasant unto thy soul,” Kohelet counters “in much wisdom is much vexation; and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow.” While Job’s perspective that it is better to have never been born at all pops up amidst the musings, it is negated by Solomon’s personal opinion that better than being enraged at having been born, “enjoy life with the wife you love. Enjoy every day of your short life.”

When there is no Maat-style manual for life, then, when chaos — the authors’ preferred translation for “hevel” — so often gets in the way of coherence, how should one proceed with living? Thousands of years before Sartre, Nietzsche, Freud, Camus and countless others unpacked the meaning of existence, Kohelet came to his conclusions: Love the one you’re with. Find joy in whatever you have at that moment. Obey God’s commandments.

When there is no Maat-style manual for life, then, when chaos — the authors’ preferred translation for “hevel” — so often gets in the way of coherence, how should one proceed with living? Thousands of years before Sartre, Nietzsche, Freud, Camus and countless others unpacked the meaning of existence, Kohelet came to his conclusions: Love the one you’re with. Find joy in whatever you have at that moment. Obey God’s commandments.

Abelman and Grossman present Ecclesiastes’ ending with a parable: “Imagine you were afflicted by a strange disease. It was decreed that you would forget whatever you read the second you finished reading. You wouldn’t remember any lessons, how it forged your skills, the drama that the characters experienced and the emotions you felt following their journey … You could read the same thing two or three times, and each time would feel as new. Would you stop reading? We presume you would want to read whatever gives you pleasure during those moments. Not for whatever supposed life lessons you would gain — rather, for the excitement that the book would give you during the moment of reading itself. For Ecclesiastes, this is life.”

Like Moses’ speech on the eve of his people’s entry into the Promised Land, Ecclesiastes is the handing over of recommendations and legal injunctions meant to guide the coming generation after the prior one passes away.

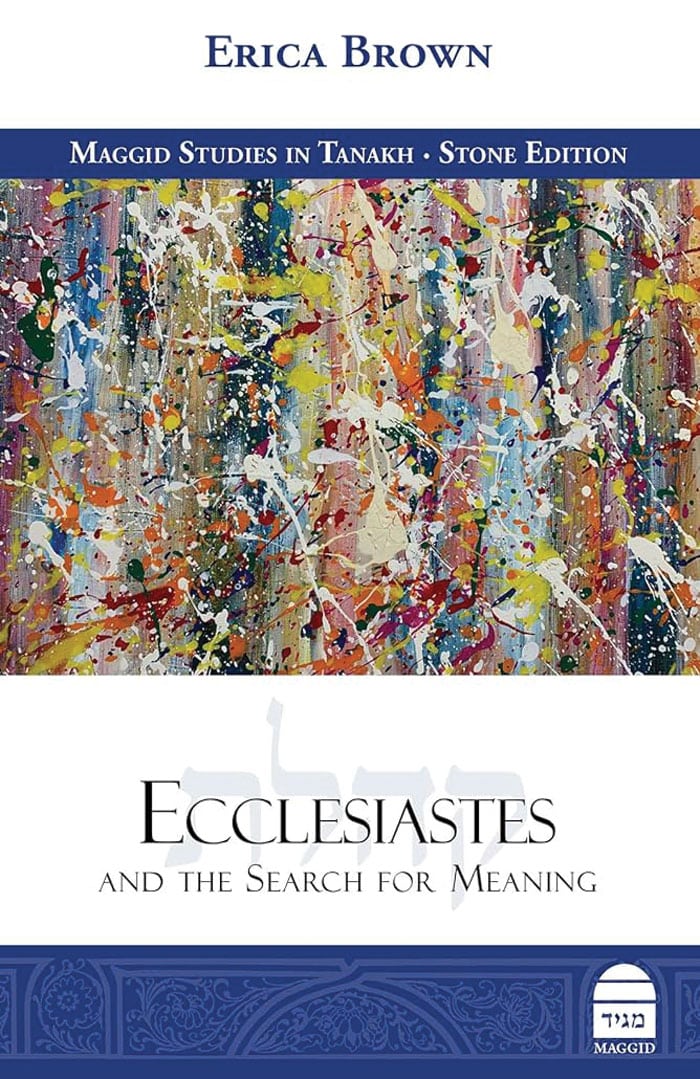

For Erica Brown, the Vice Provost for Values and Leadership at Yeshiva University, Ecclesiastes is an exercise in meaning-making. Meditating on the book’s major themes, informed by learned discussions of diverse thinkers Tolstoy and Chekhov, Montaigne and Maimonides, the modern organizational psychologist Adam Grant, the poet Amanda Gorman, and countless others, Brown reads the biblical book as an ethical will. Like Moses’ speech on the eve of his people’s entry into the Promised Land, Ecclesiastes is the handing over of recommendations and legal injunctions meant to guide the coming generation after the prior one passes away.

For Erica Brown, the Vice Provost for Values and Leadership at Yeshiva University, Ecclesiastes is an exercise in meaning-making. Meditating on the book’s major themes, informed by learned discussions of diverse thinkers Tolstoy and Chekhov, Montaigne and Maimonides, the modern organizational psychologist Adam Grant, the poet Amanda Gorman, and countless others, Brown reads the biblical book as an ethical will. Like Moses’ speech on the eve of his people’s entry into the Promised Land, Ecclesiastes is the handing over of recommendations and legal injunctions meant to guide the coming generation after the prior one passes away.

Extracting major themes from each of Ecclesiastes’ chapters, she offers both a helpful summary of contemporary scholarship and her own keen insights. As a representative sample, in her reading of Chapter 2, titled “Does money matter?” she notes that “in Kohelet, money is not used, it is discussed.” It is “an inheritance, a nuisance, and a means to purchase pleasure or power. It is more often a source of anxiety and heartache than it is worth.” Utilizing Marinus van Reymerswale’s 16th century painting “The Money Changer and His Wife,” Tevye’s “If I Were a Rich Man” from “Fiddler on the Roof,” The New York Times’ ethicist Kwame Anthony Appiah, Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations” and Maimonides’ teaching that a Torah sage should be “stringent with himself in his accounting” and not overly demanding of people who owe him loans, Brown offers a prism through which to ponder Kohelet’s accumulation of wealth: “I gathered me also silver and gold, and treasure such as kings and the provinces have as their own … And I hated all my labor wherein I labored under the sun, seeing that I must leave it unto the man that shall be after me.” Mind the gaps, Brown keenly observes, writing, “One wonders what Kohelet might have thought about other, positive uses of money like giving charity, supporting one’s family, or engaging in business with honesty and integrity. This we will never know.”

We read the book over Sukkot, Brown argues, because, after the personal transformation we experience on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur… “a new person needs a new home.”

We read the book over Sukkot, Brown argues, because, after the personal transformation we experience on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, of contemplating the “crushing pain and soaring joy” of the High Holy Day season, and of the nature of life itself with its ever-changing seasons washing away our breath’s fleeting contributions and accumulations, “a new person needs a new home.” That home, the sukkah, in its spareness, ensures that we bring into its makeshift walls only that which provides this simple structure with the simple satisfactions life makes room for. “You can bring in it only that which you truly need and those who truly mean the most to you.”

To the 19th century Polish sage Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, the possibility that the author of Ecclesiastes perceived the making of many books to be a negative pursuit couldn’t possibly be. Rather, in Rabbi Berlin’s reading, cited by Abelman and Grossman, what King Solomon actually meant was the opposite of the verse’s plain meaning. “If one wants to offer innovative insights [chidush] and glorify the Torah, one should be conscious of two matters,” Berlin writes in his commentary the “Haamek Davar.” “The first is that because there is no limit to the writing of books, you should write down each and every insight you have … and the second is, since ‘much study is a weariness of the flesh’ you should speak often with those ‘weary of flesh,’ namely your students,” those who strenuously force you to sharpen your thinking.

In Koren’s threefold cord of commentaries on Kohelet, seasons of students have been given interpretive riches with which to sharpen their thinking as they turn the pages of the musings of a monarch from millennia ago — about life, its limits, its possibilities, and what truly matters under the sun.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is the Senior Adviser to the Provost and Deputy Director of the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought at Yeshiva University.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.