Itay Benda, an Israeli singer, has found a unique way to advocate for Israel.

On any given day — except Saturday — he goes live on his social media accounts and sings to people from all around the world. With close to 540,000 followers on TikTok and 347,000 on Instagram, it’s a powerful way to connect and show that Israelis are not what many assume. They are friendly, loving, and accepting of others, whether they’re Christians, Muslims, Hindus — or anyone else.

Of course, things don’t always go as planned.

Such was the case this past May, after a barrage of ballistic missiles from Yemen struck near the main terminal at Ben Gurion Airport, disrupting flights and injuring eight. That same day, a man appeared on Benda’s TikTok Live. He wore a keffiyeh and held a guitar.

“Where are you from?” Benda asked.

“From Yemen. I’m Houthi,” the man replied.

Benda is careful not to reveal his identity until after he sings. He usually sings in the language of the person he’s speaking with — he performs in 50 languages, including several Arabic dialects — and does it so well that people often mistake him for one of their own.

When he finished singing, the Houthi was clearly moved. He clapped his hands.

“Your voice and play are good,” he told him.

Benda then revealed he’s Israeli and currently lives in Los Angeles. The Houthi was taken aback. He claimed that the IDF had bombed the airport in Yemen.

“Because Houthis send missiles to our airport,” Benda said.

The Houthi replied that he didn’t know anything about that. “We will destroy Israel. We will kill anyone from Israel, all the Jews!” he said.

“Why? We just sang together. Now I’m your enemy?” Benda tried to reason with him, but to no avail.

Thankfully, not every interaction ends this way. While some people hang up, curse, or refuse to continue the conversation, Benda says his music often opens the door to a real exchange. “My rabbi once asked me, ‘Doesn’t it hurt you when people curse you?’ To tell you the truth, not at all. The curses and the hatred are meaningless,” Benda said.

“If I sing and you tear up before my eyes, and I move you and touch the deepest emotional strings of your heart — and then you curse me — I don’t believe those curses.”

In a conversation with The Journal, Benda said he can never predict what kind of reaction he’ll get. People from countries such as Syria, Jordan, and Egypt have responded with everything from warmth to hostility. “I’m surprised every time. Each time I hope for love — and sometimes I get it, and sometimes I don’t. I never know what to expect. You can’t predict or assume, ‘I’ll get love from Syria and hate from Kuwait.’ It really depends on many factors — where the person was born, how old they are, etc. Generally, younger people tend to be more brainwashed compared to older ones. There are no rules.”

Benda moved to Los Angeles from Jerusalem 15 years ago. In Israel, he was known as a singer and drummer, but he also plays keyboard and guitar. In 2019, he uploaded a video of himself singing in Persian. Almost immediately, he received thousands of requests to perform a well-known Iranian protest song.

“That clip got 20 million views and brought in over 200,000 Iranian followers, from Iran and around the world,” said Benda. “So I started singing more Persian songs, and before long, I became well-known in the Iranian community. They began inviting me to perform at their events.”

Benda’s ability to sing in perfect Farsi has many convinced he’s Iranian. At weddings and bar mitzvahs, people often approach him speaking in Farsi, either requesting a song or offering a compliment. They’re always surprised when he replies — in flawless Farsi — that he doesn’t actually speak the language.

“God blessed me with an ear for nuance,” he said. “I enjoy listening to different Arabic dialects and learning them. I love the challenge of pronouncing sounds that don’t exist in Hebrew. When I learn a song, I focus on every word’s pronunciation — and what I hear is what I sing.”

Since the conflict with Iran intensified, Benda has been singing to many Iranians still living in Iran. As usual, he refrains from revealing that he’s Israeli until he finishes performing. So far, he says, most of the responses have been positive.

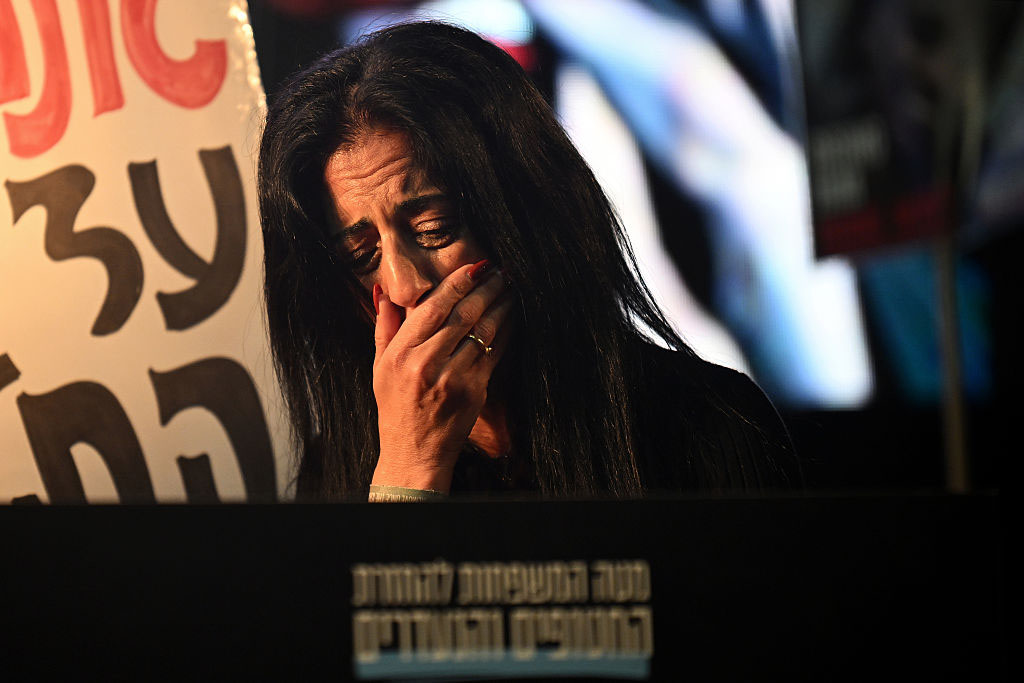

In one video he uploaded, an Iranian woman joins him live. Her face is blurred to protect her from the regime, which would undoubtedly punish her for speaking to the “enemy” — an Israeli. The conversation unfolds like this:

“Can I sing you a song?” Benda asks, and begins singing a beloved Persian tune.

Although her face is hidden, her voice reveals emotion — perhaps even tears.

Only after the barrier is broken through music does Benda reveal, “I’m from Israel—man doost daram,” which means “I love you” in Persian.

The woman replies, “Man doost daram.”

There is no hostility, no hatred — just two people from enemy nations, connecting through music and expressing hope for peace. “From my long-standing relationship with Iranians, I can say they love Israelis and see Israel as their escape route to freedom,” Benda said. “They understand that this war is their government’s war — a government they’ve been suffering under for years.”

Nine years ago, Benda became religious and has since made Torah study part of his daily routine. Each morning, he studies Gemara with his chavruta (study partner), before returning home to record, rehearse, and respond to requests from his growing online community.

One afternoon, he’s joined by two young men living in Belgium. They are friends — one from Syria, one from Morocco. Benda sings to them in Syrian Arabic and then in Moroccan Arabic. Their faces light up with surprise and delight. He then tells them he’s an Israeli living in LA. “You have a good voice,“ the Syrian guy tells him and quickly adds, “I like Jewish people but I don’t like Zionists.”

This is Benda’s chance to give the young man a little history lesson. He tells him how Israelis and Iranians used to be friends until the Persian revolution in 1979, and that in Israel, Muslims, Christians and Jews live side-by-side in peace.

“Let me tell you something, people who don’t agree with Zionism, means they don’t agree with Judaism, because Jewish and Zionist is one. Believe me, we want peace.”

The Syrian softens up. He agrees that the Islamic Republic in Iran is the problem. “I’m Jewish and I love you a lot,” Benda tells him in Arabic. “Insha’Allah, we’ll have peace. I want you to know the Zionists love you.”

For Benda, this is his way to “build bridges, break stigmas and share the truth,” Benda told the Journal. “Music heals, connects, and reaches deeper than we realize. I use it to spread good, bring people together and advocate for Israel.”