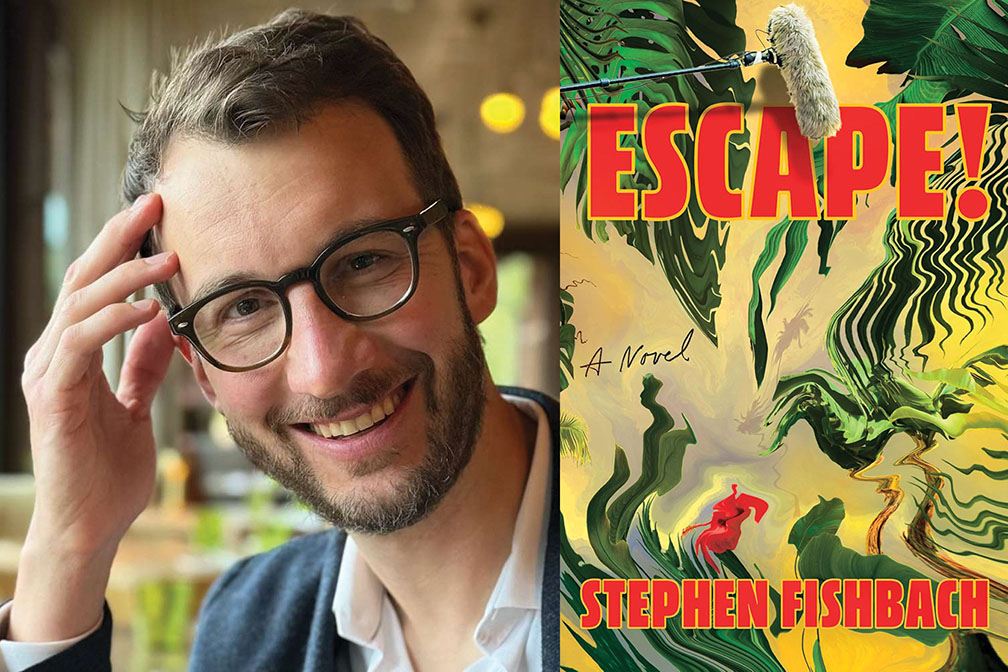

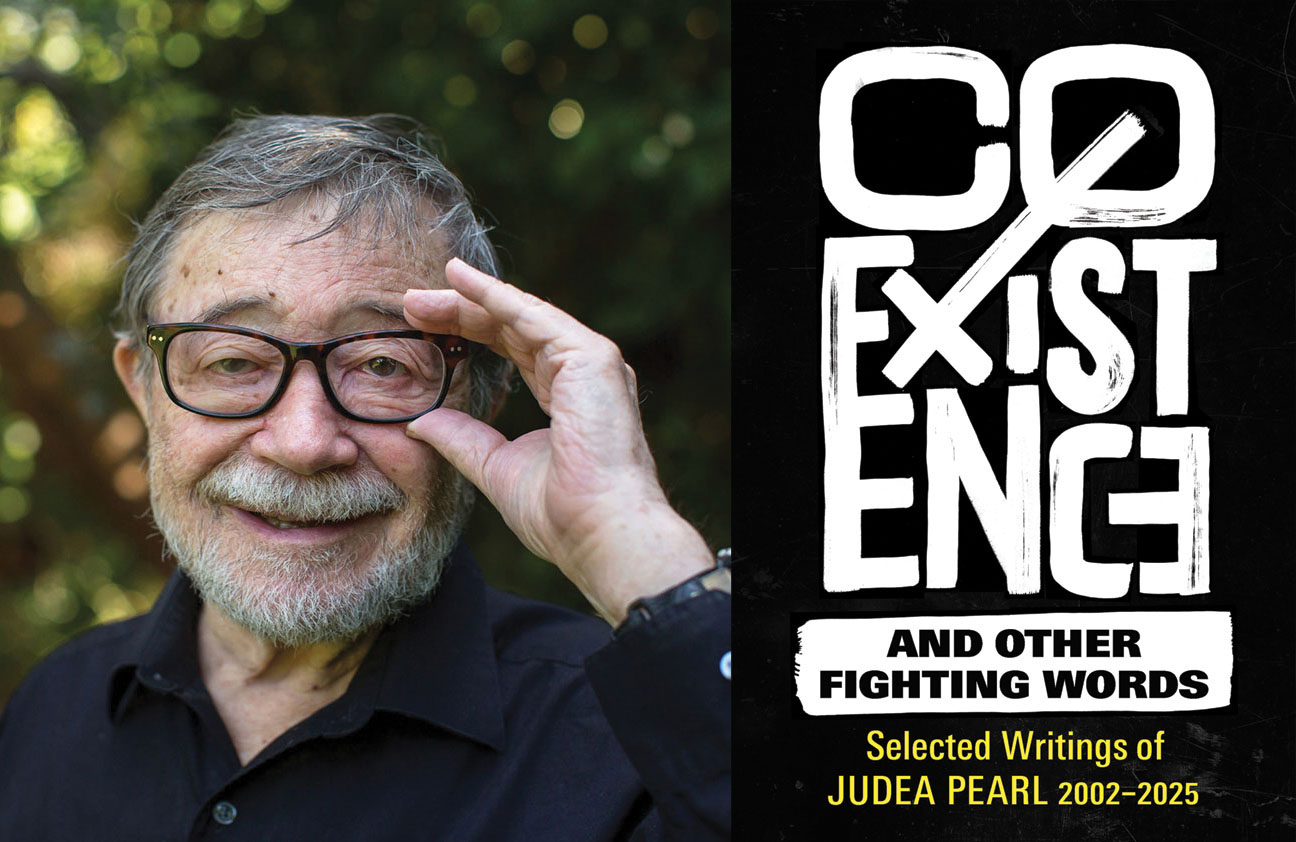

“Coexistence and Other Fighting Words: Selected Writings of Judea Pearl 2002-2025.” Political Animal Press (2025). 192 pages.

“Conventional wisdoms were mighty unkind to us, so our sanity demanded that we challenge those conventions and, in due course, we have learned to challenge all conventions. Thus, is my Jewishness a blessing or a burden? Do I prefer the trails of the scouts to the safety of the bandwagon? You bet I do. It is only from those trails that I can see where the voyage is heading, and it is only from there that I can discover greener pastures. I am Jewish, and I doubt I would be in my element elsewhere.” — Judea Pearl

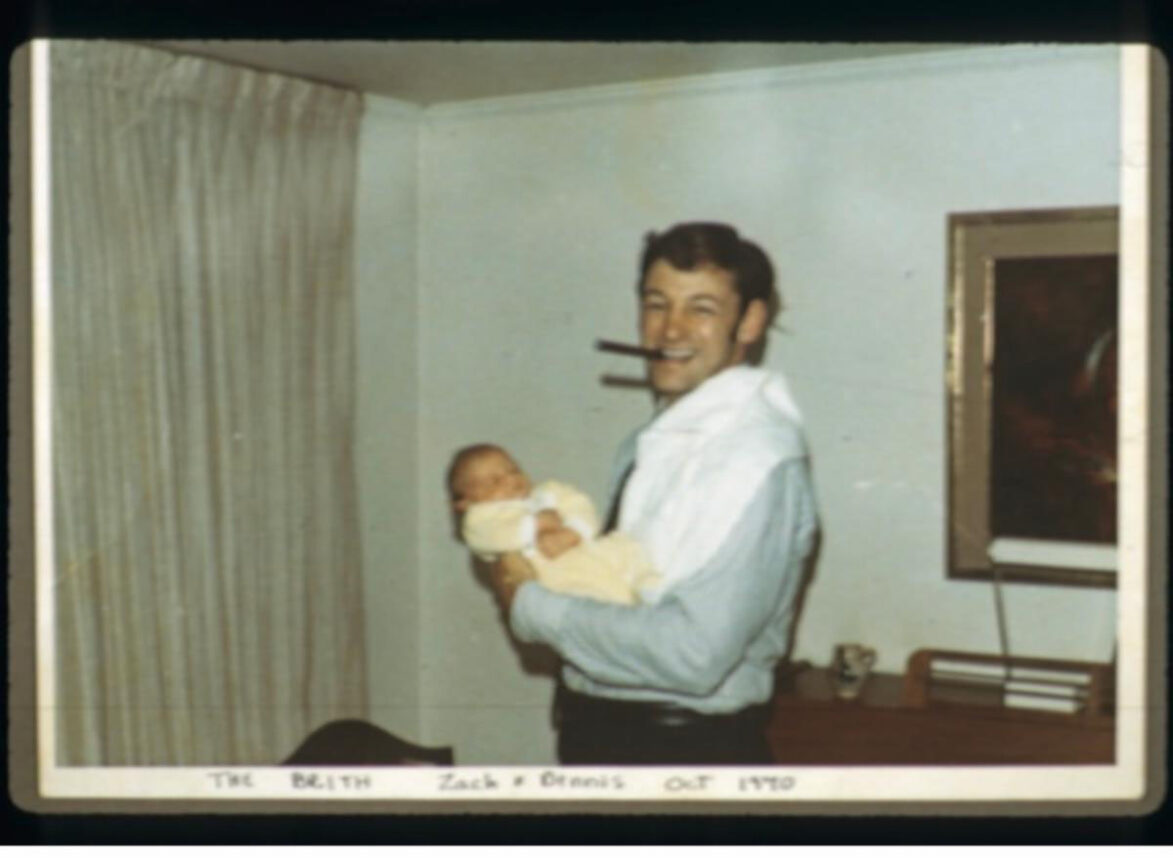

Professor Judea Pearl was born in Bnei Brak, in what was then the British Palestinian Mandate. Family members, including his maternal grandparents, were murdered in the Holocaust. Aged 11, playtime with friends abruptly ended with Egyptian warplanes bombarding his town. He joined the IDF; lived on a kibbutz; studied engineering on the way to a stunningly successful scientific career; married and had three children, two girls and a boy.

In 2002 Pearl and his wife Ruth experienced an unimaginably horrific tragedy. While on assignment in Pakistan, their son Daniel, a much-loved reporter for the Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped by ISIS, and murdered. The killers made a gruesome video of his final moments. On it, Daniel—“Danny”—says his last words: “My father is Jewish, my mother is Jewish, I am Jewish. Back in the town of Bnei Brak, there is a street named after my great-grandfather, Chaim Pearl, who was one of the founders of the town.”

You might expect a man who’d experienced so much suffering to be broken—but that would mean you don’t know Judea Pearl. In this selection of essays, op-eds and speeches, the first piece written six months after his son’s murder, Pearl gives us words that are, yes, sometimes heartbreaking, but also funny, profound, scrappy, informative and strikingly prescient. Pearl deserves to be listened to not simply because of who he is, or because he’s such a marvel of resilience, but because his experience, maybe, gave him a way to see what too many others didn’t—yet—and articulate it so brilliantly.

Pearl deserves to be listened to not simply because of who he is, or because he’s such a marvel of resilience, but because his experience, maybe, gave him a way to see what too many others didn’t — yet — and articulate it so brilliantly.

“Barbarism, often cloaked in the language of ‘resistance,’ has gained acceptance in the most elite circles of our society,” he writes in a piece marking the seventh anniversary of Daniel’s murder. In an observation that echoes in our post-October 7 world, he notes how “Some American pundits and TV anchors didn’t seem much different from Al Jazeera in their analysis of the recent war in Gaza,” giving “Hamas legitimacy as a ‘resistance’ movement” and bemoaning the “cycle of violence,” in which Palestinian terrorism and Israel’s response to it are cast as moral equals. “Civilized society, so it seems, is so numbed by violence that it has lost its gift to be disgusted by evil,” he writes.

As a professor for fifty years at UCLA, Pearl provided breakthroughs that paved the way to AI. In 2011 he received the Turing Award, often called “the Nobel Prize of Computing.” Meanwhile he saw Israel-hating fanatics increasingly mob his campus, while his colleagues either coddled or egged the protesters on, or shrank in fear. But Pearl took them on with courage and clarity.

“I believe that one of the biggest mistakes Jewish advocacy has made in the past decade is to argue that anti-Zionism is dangerous because it is a thin cover for antisemitism,” he writes in a 2009 piece about UC Irvine, where the Muslim Student Union celebrated what was called a “week-long lynching of Jewish identity.” “We should have exposed the immoral character of anti-Zionism in itself and insisted that Israel’s statehood be recognized for what it is, a fundamental aspect of Jewish identity.”

Anti-Zionism, he argues in another piece from the same year, is much worse than antisemitism. “Modern society has developed antibodies against antisemitism but not against anti-Zionism,” he explains. “Today, antisemitic stereotypes evoke revulsion in most people of conscience, while anti-Zionist rhetoric has become a mark of academic sophistication and social acceptance in certain extreme yet vocal circles of U.S. academia and media elite.” Anti-Zionist rhetoric also sets back the best prospect for peace in the Middle East: a two-state solution. And while antisemitism rejects Jews as equal members of the human race, “anti-Zionism rejects Israel as an equal member in the family of nations.”

He long ago recognized that it was necessary to fight using new language. “The term ‘antisemitism’ connotes submissive begging for protection,” he told a group of graduating Jewish UCLA students in 2019, “and should be replaced by a fighting word ‘Zionophobia’—the irrational fear of a homeland for the Jewish people. It rhymes with Islamophobia on purpose, of course. When you call someone a ‘Zionophobe,’ it means: ‘If you deny my people’s right to a homeland, something is wrong with you, not me.’” If we use the word often enough, he says, it will become as ugly, as emblematic of racism, as it deserves to be.

Fittingly for someone who dubs himself “the Smiling Zionist,” Pearl often finds humor in his antagonists’ antics, even if the jokes are sometimes a bit dark. “I believe everyone would like to find out from BDS supporters how peace can emerge between two partners,” he told the UCLA Debate Union in 2017, “one insisting on seeing the other dead and the other insisting on staying alive, no matter how glamorous the coffin.”

And in an essay from 2018, he notes how: “Each year, in preparation for Israel’s birthday, newspaper editors feel an uncontrolled urge, a divine calling, in fact, to invite Arab writers to tell us why Israel should not exist. This must give them some sort of satisfaction, such as we might have in inviting officials of the Flat Earth Society to tell us why Earth is not, could not, or should not really be round, and to do so precisely on Earth Day, lest the wisdom would escape anyone’s attention.”

The entire Israel-Palestinian conflict, he writes in 2006, can be encapsulated in two words: “postage stamp.” In 1937, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, by far the most ambitious hardliner of all Zionist leaders, wrote that “we beg merely for a small fraction of this vast piece of land.” That same year, the British-appointed Peel Commission proposed a two-state solution, with a Jewish state on approximately 25% of the current area of Israel. The Zionist leadership accepted, after a fierce debate, while the Arabs responded that there was to be no Jewish state, ever, on any part of the land: “Not even the size of a postage stamp.”

That attitude has kept the region mired in terrible conflict, when the Palestinians could have been celebrating their independence these past 77 years alongside Israel. Pearl traces some of the historical highlights, or lowlights: like the Arab League summit meeting in Cairo, 1964, when Jordan controlled the West Bank and Egypt governed Gaza. A peace agreement with Israel that year would have created a Palestinian state. Yet the Arab League collectively called for “the final liquidation of Israel” and formed the PLO.

Then there’s the Arab Summit at Khartoum in August, 1967, when Israel was offering to return the land they’d taken in the Six Day War in return for peace—an offer that again would have created a Palestinian state. The Khartoum conference responded with the “Three Nos”: “No recognition, no negotiation, no peace.” Arab rejectionism, bolstered by anti-Zionist Westerners, then gave steam to Israeli settlers, who figured that as long as Israel’s enemies were unremittingly hostile, they’d better adopt an attitude of total strength.

In 1988 Arafat formally recognized Israel’s existence and the Oslo process began. Many Israelis thought the “postage stamp mentality” was finally dead. But when the talks fell apart, Israeli peace camp leaders publicly acknowledged that they’d been dupes. Ordinary Palestinians had seen Arafat’s moves “as a ‘Trojan Horse’ in a grand scheme aiming toward a Palestinian state ‘from the river to the sea.’” In our post-October 7 world, the “postage stamp mentality”—uncompromising, genocidal, hailed by ignorant Westerners—looks more unfettered than ever.

And Jews, Pearl emphasizes, are Israel. In an essay from 2006, he points out that much of the criticism of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad for posting a Holocaust-denial conference misses the point. “I hear tons of well-deserved condemnations of Ahmadinejad for orchestrating such an offensive conference,” he writes, “but not one voice saying: ‘Hey man! What a waste of time. We don’t need a Shoah to justify a Jewish state on that sliver of land. Our history was born there, and our collective consciousness has remained there.’ I fear that as the buzz winds down and the dust settles, there will be only one thing remembered from the Holocaust Conference in Tehran: Israel and the Holocaust are one. That is, Israel owes its existence to one and only one factor: European guilt over the crime of the Holocaust. Once this is established, the next obvious question is: Why should the Palestinians pay for Europe’s crime?”

This is, in fact, exactly the question Jews are continually confronted with, but it turns history on its head. Jews, Pearl notes in a 2008 debate with law professor George E. Bisharat, have maintained spiritual and historical ties to their historical homeland since their second century expulsion by the Roman Empire. Furthermore, “the idea that the homeless must forever remain homeless is morally unacceptable.”

Palestinian claims to deep historical roots on the land, on the other hand, are all too thin. Pearl imagines politely asking such individuals: “Can you name a Canaanite figure who you are proud of? A Canaanite poem that you enjoy reciting? A Canaanite holiday that you celebrate? A Canaanite leader who is a role model to your children?” He notes that if you replace the word “Canaanite” with “biblical,” “you will find four questions that every Israeli child can answer half asleep.” He hopes such considerations will someday “mitigate the Palestinian claim to exclusive ownership of the title ‘indigenous people’ and, God-willing, usher in a genuine reconciliation effort based on mutual recognition and shared indigeneity.”

In an essay from 2021, Pearl recalls Eugène Ionesco’s 1959 play “Rhinoceros.” In it, a stray thick-skinned beast stampedes through a peaceful town, raising much dust and trampling a woman’s cat. The townspeople decide to ignore it. It’s a “stupid quadruped not worth talking about,’’ one citizen tells the town’s one doubter, while another shrugs, “You get used to it.” An ethical debate develops over the rhino way of life versus the human way of life, after which the townspeople adopt the novel new ethic and are transformed into rhinos. The hero “finds himself alone, partly resisting, partly enjoying the uncontrolled sounds coming out his own throat: ‘Honk, Honk, Honk.’”

Pearl comments that those sounds from Ionesco’s play sometimes echo in his ears, such as in 2009, “when Hamas gave its premiere performance at UCLA.” That “Human Rights and Gaza” symposium, which one reporter called “a reenactment of a 1920 Munich Beer Hall,” ended with panelists leading the excited audience into chanting, “Zionism is Nazism” and “F—, f— Israel,” “in the best tradition of rhino liturgy.”

But Pearl notes that “the primary impact of the event became evident the morning after, when unsuspecting, partially informed students woke up to read an article in the campus newspaper titled, ‘Scholars Say Attack on Gaza an Abuse of Human Rights,’ to which the good name of the University of California was attached, and from which the word ‘terror’ and the genocidal agenda of Hamas were conspicuously absent.” The rhinos were on the warpath.

Pearl, alarmed, called colleagues to discuss how to best support their Jewish students, but discovered that a few had “already made the shift to a strange-sounding language, not unlike ‘Honk, Honk.’ Some had entered the debate phase, arguing over the rhino way of life versus the human way of life, and the majority, while still speaking in a familiar English vocabulary, were frightened” beyond anything he had seen at UCLA in his then-forty years on its faculty.

He describes colleagues who told him about lecturers whose appointments were terminated, “professors whose promotion committees received ‘incriminating’ letters, and about the impossibility of revealing one’s pro-Israel convictions without losing grants, editorial board memberships, or invitations to panels and conferences. And all, literally all, swore me to strict secrecy. Together, we entered the era of ‘the new Marranos.’”

Through it all Pearl has kept fighting and writing, drawing inspiration from his Jewish heritage.

“I see Jews as the scouts of civilization,” he tells the Jewish UCLA graduates of 2019, “the ones who question conventional wisdom and constantly seek the exploration of new pathways.

Through it all Pearl has kept fighting and writing, drawing inspiration from his Jewish heritage. “I see Jews as the scouts of civilization,” he tells the Jewish UCLA graduates of 2019, “the ones who question conventional wisdom and constantly seek the exploration of new pathways.”

“Abraham questioned the wisdom of idolatry; Moses questioned the wisdom of servitude and lawlessness; the prophets questioned institutional injustice; and so the chain goes on from the Maccabees, Jesus, and Spinoza to Marx, Herzl, and Freud down to Einstein, Gershwin, the Zionist Chalutzim, who created the miracle of Israel, and down to the civil rights activists of the 1960s.

“As individuals, we do not consciously choose this lonely role of scouts, border-challengers, or idol-smashers. It has penetrated our veins, partly from the Bible and the Talmud through their persistent encouragement of curiosity, learning, and debate, and partly from our free-spirited parents, uncles, and historical role models. But mostly, this role has been imposed on us by the travesties of history.”

Irrepressible optimist that he is, he embraces it, because with the loneliness comes creativity. Pearl’s book is a tonic for anyone who despairs at today’s world. Drink it.

Kathleen Hayes is the author of ”Antisemitism and the Left: A Memoir.”