Long preceding the current war, many Jews felt that the United Nations and its satellite agencies trafficked in bias and injustice; the events and discoveries of the last 21 months cemented this feeling. Perhaps then Jewish Journal readers might appreciate “Fundamentally,” the debut novel of Nussaibah Younis, which satirizes a Middle East-based UN agency and its workers. Called UNDO, short for the United Nations Deradicalisation Organisation, the fictional (but realistic) agency aims to rehabilitate ISIS brides through moderate Islam. Younis holds a Ph.D. in International Affairs and designed deradicalization programs for Iraq, and her protagonist, Nadia Amin, a sweary, godless, South Asian, bisexual former Muslim woman, does something very similar.

The novel revolves around Nadia meeting ISIS bride Sara, in whom she believes she’s found an alternate version of herself, a self that, instead of abandoning Islam for drunken hedonism and higher education, was groomed at fifteen, left school and England, got married off to successive ISIS husbands, and ended up in an Iraqi camp cloaked in a niqab. Nadia and Sara share a similar background and sense of humor. But ultimately, there is a question about whether their worldviews can ever be reconciled.

Meanwhile, in the background, there’s the UN. The people who populate the UN base where Nadia lives and works are caricaturesque in nature: Imagine “Emily in Paris” but with Emily played by an actor who is South Asian and a little zaftig, set in Iraq instead of Paris, and in the UN instead of a marketing company. Nadia sleeps with Tom, whose role is to be gorgeous (like Gabriel, Alfie, and Marcello in “Emily in Paris”), listens to quips by gay Pierre (the exact double of Luc in “Emily in Paris”), and gets everything wrong. At the end, we learn that a lot of UN workers and programs get a lot of things wrong, though they are good at covering up their mistakes. Over drinks and MDMA, fictional UN workers laugh over their fictional mess-ups: One set up a peace committee in South Sudan and gave the participants t-shirts to encourage team spirit only to find they were wearing them as militia uniforms when attacking a rival tribe; one established a female empowerment program in Sierra Leone, and all the participants opened brothels; one helped a local NGO obtain food and medicine in Yemen only to learn they had sold their products at a mark-up and went to live in the Algarve with the profits. I added my own not-so-fictional example in the margins: “One ran an aid agency in Gaza, and several personnel were involved in a murderous invasion of Israel, taking civilians hostage, and even detaining them in UN facilities.” Lol?

At the end, we learn that a lot of UN workers and programs get a lot of things wrong, though they are good at covering up their mistakes.

Further mocking the UN and its out-of-touch sensibility, when Nadia proposes UNDO, she is told that programs should be “inclusive of all genders and none, of all faiths and none, and of all sexualities and none.” Although Nadia explains that ISIS is not particularly diverse in its recruitment of women (“people socialised as women,” she’s corrected) and if they weren’t “cisgendered, straight and Muslim,” they would be beheaded, she’s encouraged to still try to be more inclusive. She agrees, but, she says, “don’t expect me to go searching for gay intersex Jews next time we’re in the camp, because, newsflash, there aren’t any there!”

These identities—gay, intersex, Jews—are obviously the most impossible, the most heinous, in ISIS, and, it would seem, Iraq (sad to read, especially as the literary market is surging with the legacies of Iraqi Jews, Linda Dangoor’s cookbook, “From the Tigris to the Thames” the most recent). Israel also takes a few hits in the novel. In another painfully glib moment, the Iraqis and UN workers play the classic icebreaker game of “Two Truths and a Lie,” and the minister comes up with what is apparently a hilarious one (a character laughs so hard, tears run down his face): “Palestine, Palestine, Israel.” If Nadia is also laughing, she doesn’t mention it, but she does say that working in the sanitized world of the UN, she feels out of place and wishes she were back among the people in the demonstrations that had always been part of her life: “ever since I was a toddler … [I was] demanding intervention in Chechnya, cheering on the intifada.” UNDO imports a hippy-convert (“revert”) American sheikh to teach moderate Islam to the ISIS brides; when he admits to having vacationed in Tel Aviv, the camp women toilet paper his cabin. And there’s the rub: On this one issue, it would seem that Nadia’s views and those of Sara, the ISIS bride, might not be so incommensurable.

This book will likely cut close to the bone for many Jewish readers, even as it entertains. I am not sure it’s for everyone. I read it with my book club (white, British women, of Christian or no faith), and they found the characters too one-dimensional and unlikable, the story unoriginal (“I already read all about Shamima Begum in the papers!”), and the ending unsurprising. One even took umbrage at the fact that Nadia devours a Milk Tray—a classic big variety box of British chocolates—and then regrets having too many hazelnut swirls (“There are only two in a box of thirty-six!” raged my friend). Personally, I found it funny, even when it was uncomfortable, and very timely.

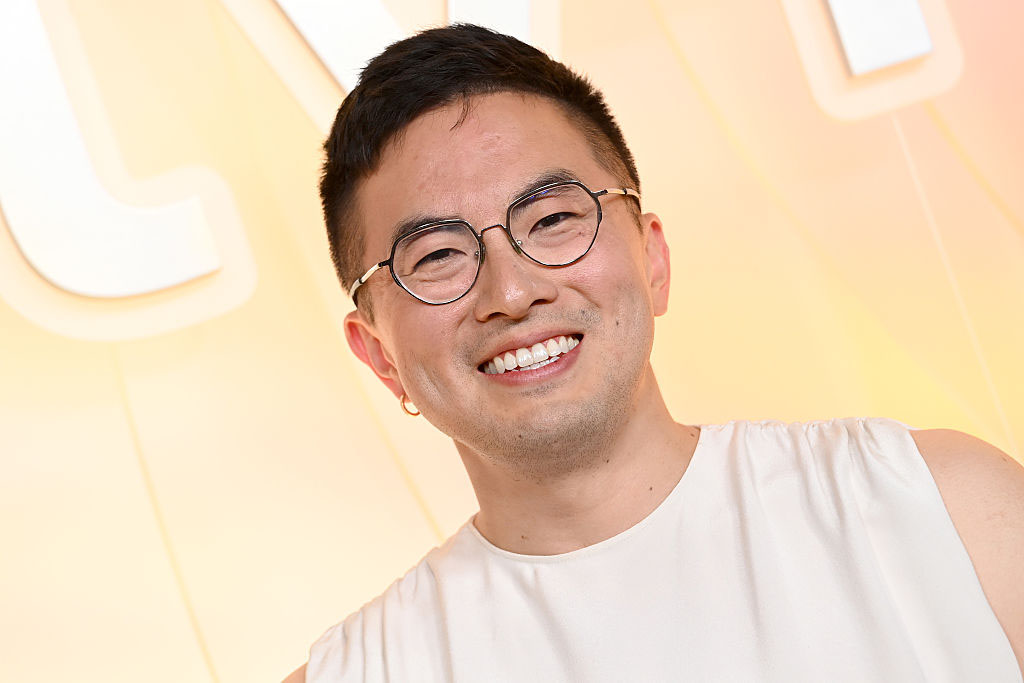

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”