Reading Charles Dickens is usually an unalloyed pleasure; there is probably not another writer in English as entertaining. But reading “Oliver Twist,” you’re forced to contend with Fagin, the leader of a band of young petty thieves, who Dickens repeatedly refers to as the “Jew.” (Three-hundred-twenty-six times, if you’re keeping count.) To make matters worse, in the illustrations George Cruikshank drew for the original edition, Fagin is a stereotypical Jew: prominent nose, hooded eyes, bearded and dressed in black; he would look right at home among the racist caricatures in Der Stürmer.

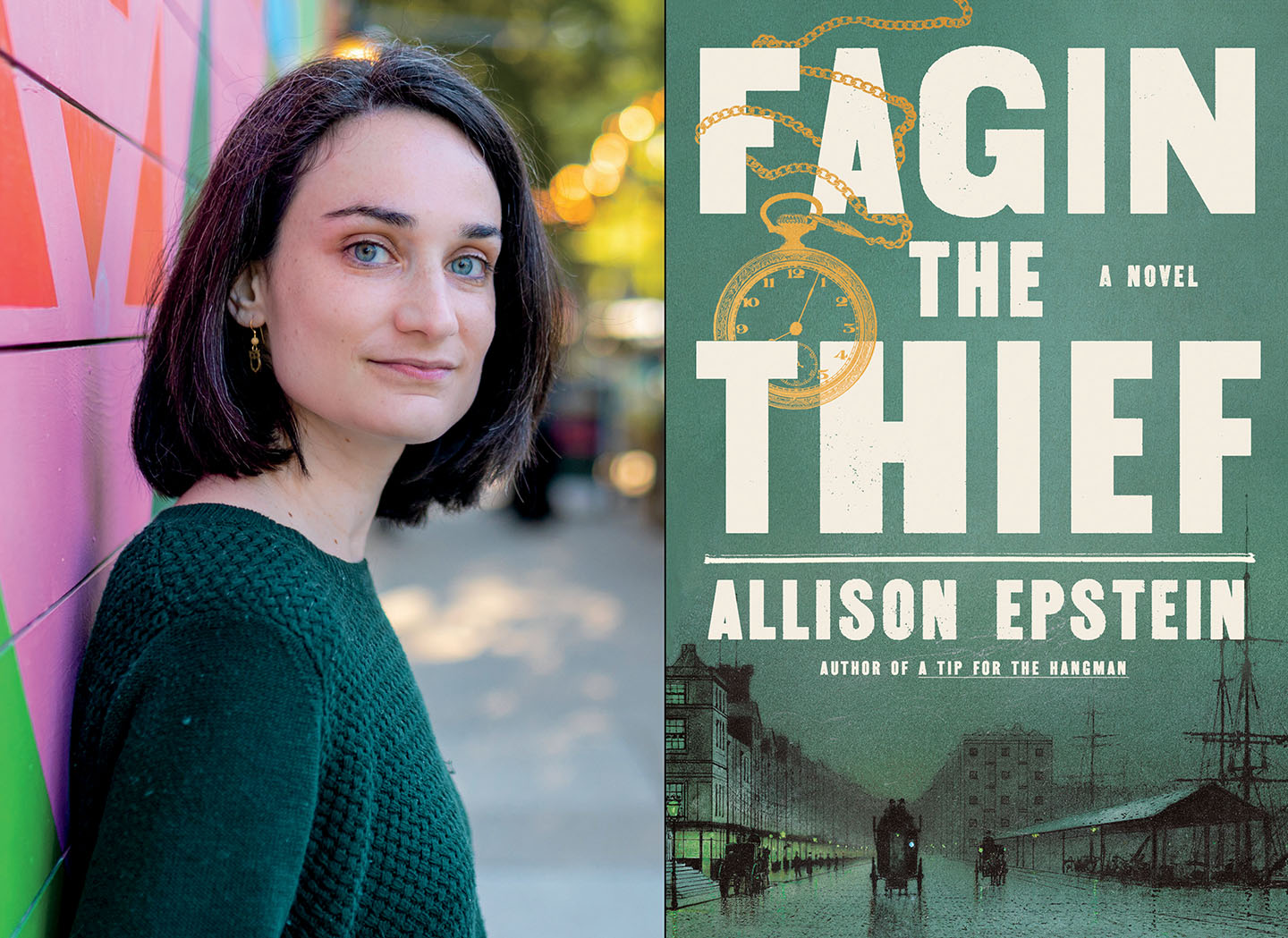

For Allison Epstein, author of the recently published “Fagin the Thief,” Fagin was the first Jewish character she encountered in fiction, in a production of the musical “Oliver!,” one of her grandmother’s favorite musicals. “There was something just electric and alive about that character in a way that I hadn’t seen and in a way that really fascinated me,” she said. She fell in love with the character, and when she was old enough, she decided to read the novel. She found the experience of “meeting Dickens’ Fagin is very different” than the musical. “There’s still something in there that I love and that’s important to me, but man, Dickens, you did him so dirty. And I’ve just kind of been mad about it ever since.”

The desire to set things right animates “Fagin the Thief.” Epstein’s Fagin, while by no means an admirable character, is a fuller, more nuanced — and more Jewish — portrayal. For one thing, she gave him a first name, Jacob, and a mother, Leah, who makes her living sewing and mending clothes. They live in a tenement apartment downstairs from the local rabbi, in Stepney, Victorian London’s Jewish ghetto, home to some 400 Jews who have, Epstein writes, “to all intents and purposes built their own country, half a mile square in which they need not be outsiders.” But to Fagin, Stepney is “a claustrophobic nightmare where everyone knows everything about everyone.”

He escapes, even if only a short walk away, where he is befriended by Leftwich, a dandyish pickpocket who takes him under his wing. Fagin is an adept thief, which becomes a source of pride; it’s better to be called a thief, he thinks, than to be called a Jew. Tiring of splitting his take, Fagin breaks up the partnership and goes into business for himself.

Fagin, who today would probably be accused of “grooming” children to be thieves, actually likes children. In the sections of the book that take place in the early 19th century, Fagin takes delight in children, and it ends up that he’s a very good teacher, even though he’s “a man who teaches children how to steal,” she said. But Fagin, Epstein writes, “adapts his approach without thinking about it, molding himself into the instructor each of them needs,”

Epstein tells the story on two timelines; each of the novel’s four sections begins in 1838, the year “Oliver Twist” was published. The reader first encounters Epstein’s Fagin as they do Dickens’: frying sausages over an open fire, the Artful Dodger introducing him to Oliver, newly arrived in London after escaping from the from the undertaker he was apprenticed to. The other timeline is Fagin’s bildungsroman, moving chronologically from 1793 until, at the start of part four, the two timelines meet.

The heart of that story is the relationship between Fagin and Bill Sikes. In “Oliver Twist,” Sikes, a “housebreaker,” no longer needs Fagin’s lessons, but still needs Fagin, as both a scratching post and a father figure. A violent force of nature, (“just antagonism. There’s nothing beyond that,” was Epstein’s description) Sikes was the hardest character for Epstein get a handle on. She didn’t want to write a book about him, but it was necessary, she said, because “there had to be something that kept them together like that.” She wanted to figure out why they are “still working together after all this time.” When we meet them in “Oliver Twist,” she said, “they hate each other.”

And Fagin is used to being hated. So used to it, you get the sense he’s inured himself to it. When he’s bullied by a gang, Epstein writes that “he’s faced confrontations like this more often than he could count,” calling it “the natural consequence of being visibly Jewish.” And when Bill comes to help Fagin break out of jail, he tells Fagin, “I’m not going to the gallows for your Christ-killing hide,” a sentiment that Fagin thinks is, oddly, “the most touching thing Bill Sikes has ever said to him.”

While Dickens often depicts Fagin in the most unflattering light — in a few scenes, he’s described in such vampiric terms that Epstein compared it to F.W. Murnau’s 1922 horror classic “Nosferatu” (making Fagin a Nosferat-Jew) — Epstein doesn’t think Dickens would have considered himself antisemitic. “It’s tough to put a modern definition of something like that on a person from the past.” Antisemitism was pervasive in Victorian England, “it was just the air he was swimming in at the time.”(In her research, Epstein discovered that when Lionel de Rothschild was elected to the House of Commons, whether an oath taken on the Old Testament was legally binding. She was excited to find it, since it “captured exactly the feeling that I wanted Fagin to have all the way through this book, which is the antisemitism that he’s facing is not like Eastern European state. It was just such a perfect example of that tolerance rather than acceptance.”) And, she is quick to add, that to Dickens’ credit, he “did see his portrayal of Fagin as problematic, to use modern language … and learned from it.” In later editions of the book, Dickens removed almost every reference to “Jew,” an edit which frustrates Epstein, “because then you’re just, okay, now he’s not Jewish at all.” And in “Our Mutual Friend,” his last novel, the virtuous Jew, Mr. Riah, was seen as Dickens apologizing for Fagin. Epstein doesn’t see it that way. In her author’s note she calls Riah a “harmless, dull, self-sacrificing pushover of a Jew.”

Epstein doesn’t follow “Oliver Twist” to the letter — for one thing, she has a more merciful fate for Fagin. In her research, she discovered that thieves in mid-19th century London did not hang; while Bill and Nancy’s deaths closely follow Dickens, she saved Bill’s dog, Bullseye, from the peremptory and unnecessary death he suffers in Dickens — she has a rule that “I will never kill an animal in one of my books. I don’t want to do it. It’s a cheap way to get an emotional reaction. It makes me mad every time.”

As for her human characters, she doesn’t expect “readers to come away thinking, oh, ‘Fagin is a hero, ‘or ‘I can fix Bill Sykes.’ That’s not what I’m going for. But I’d like them to finish the book and think, ‘okay, that’s how a human being might end up in a situation like that where that feels like the best path forward.’”

“I don’t expect readers to come away thinking, oh, ‘Fagin is a hero, ‘or ‘I can fix Bill Sykes.’ That’s not what I’m going for. But I’d like them to finish the book and think, ‘okay, that’s how a human being might end up in a situation like that where that feels like the best path forward.’”

Like Percival Everett’s “James,” which tells the story of Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn,” from the perspective the slave, Jim, “Fagin The Thief” recenters the narrative around a marginalized character. “It feels exciting in a way to be able to tap into that and say, here’s a story that’s in the story you won’t know that has not shared before. And it feels a little bit daring to look at the classics and say, I actually think there’s another story in here that you didn’t think you’re getting in Dickens.”