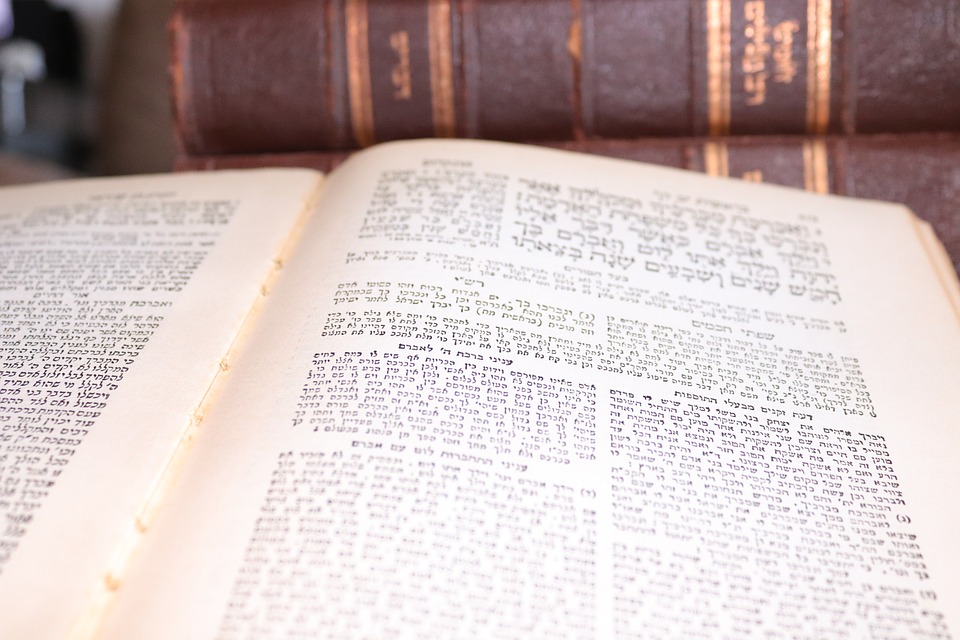

When I was in college, I fell in love with midrash. It wasn’t something I had grown up with, and one might say I came in through a back door, a secret pathway of sorts. I had never even heard the word “midrash,” but I discovered feminist midrashic poetry one day while sitting on the floor in a bookstore. “You have to enter the tents/texts,” wrote poet Alicia Ostriker, “invade the sanctuary, uncover the father’s nakedness. We have to do it, believe it or not, because we love him. It won’t kill him. He won’t kill us.” It was a strange-sounding word: midrash. But the idea of entering into the text in this way, uncovering what was hidden in the spaces and silences, sent a feeling of immense joy through my body and brain.

It wasn’t just a biblical thing, as I’d soon discover. Technically, it is; classical midrash, created by the rabbis of antiquity, is a collection of anecdotal responses to absences or ambiguities in the biblical text. It’s comprised of stories that explain these gaps and extend the biblical text in a meaningful way. Midrash is meant both to clarify uncertainties and raise further questions and possibilities. But for me, it was much more than that.

Midrash reminds us of the importance of the spaces between. It’s like writing in the margins of a compelling novel, responding to gaps and ellipses and sometimes creating more, to be responded to at another time. As a graduate student, I became further obsessed with this idea, and immersed myself in classical midrash as well as midrashic thinking in the context of contemporary literature. It became my world, the only lens through which I saw everything around me. I even wrote a dissertation, and later a book, on the topic.

I’ve always struggled to pinpoint exactly why the idea of midrash became a lifelong obsession for me rather than simply an area of academic research or interest. But over the past few months, the reasons crystallized not just into something I could understand, but also into something that tells me a lot about myself. Midrashic thinking has always felt familiar and comforting to me. The question is: Why?

It really is about the margins. It’s about the luxury of being both inside and outside of a text, a movement or an idea. It’s about having the peculiar vantage point of being simultaneously inside and outside of a world. It’s the space in which I’ve always been most comfortable, and so it’s no surprise the world of midrash felt familiar to me. I’m one of those people who struggle to fit fully into any one group or ideology. I rarely gravitate to the center of anything; instead, I hover within the margins, along the border between one idea or group and another.

It’s not that I can’t make a decision or choose a side; rather, I refuse to set up camp in a place where I can no longer see or listen to the other side. I prefer the borderlands, those spaces that allow me the wider perspective. I want to see both sides at once, and I want to think and speak from that position.

The social and political landscape of the past few months is not conducive to this way of being in the world. It demands we choose a side and not back down from that perspective, no matter what. It requires us to be relentless in our doubling down, to avoid backing away from the script set for us by our political affiliation or religious ideology. Even worse, it asks us to shun nuance and distance ourselves from complexity, but it is an acceptance and understanding of nuance and complexity that has the potential to bring us back to the center and make it difficult to perpetuate extreme viewpoints.

Many of us have felt that pull over the past few months, whether we realize it or not — that pull farther left or farther right, that urge to hold tightly to our ideologies and not let go, no matter what. The endless social media bullying and virtue signaling have played an immense role in this. I’m neither a Democrat nor a Republican, and although I tend to lean left in most cases, I reserve the right to see both sides and to alter my perspective and my position when it seems that “the other side” might be making a strong or valid point.

But this isn’t seen as good behavior by either the right or the left. “You’re either with us or you’re against us” seems to be the mindset that drives both sides. Tragically, the pandemic has become more politicized than anything in recent history. Post an article from a credible source, written by a medical expert, that suggests the coronavirus may not signal the imminent death of the majority of humans and the hounds will come from the left, banners waving and teeth gnashing. Likewise, post an opinion piece about why mask-wearing should be mandated and the right will come running with accusations of the poster being anti-American and of hastening the day when we will all be required to wear burqas indefinitely.

Isn’t there something in between?

In no way am I suggesting the answer to our social and political turmoil is the clichéd impulse to meet in the middle or find common ground. While it may be feasible in some cases, compromise can be extremely problematic in many others. It functions under the guise of making both parties happy, giving each side a little of what they want, but in many cases, compromise results only in two dissatisfied parties, both of whom feel they sacrificed something important. The initial effect may be to disarm both parties, but the long-term consequence can be bitterness and resentment, bubbling slowly under the surface but sure to burst forth at a later date. Compromise often is little more than a makeshift bandage.

In a social and political climate that only seems to be made worse by the movement of each side to its most extreme place, it might seem strange to reject compromise as a viable solution. To be sure, there is a time and place for compromise. But this may not be the time.

Rather, it might be time to start listening to the other side. It might be time to start acknowledging that no one party or ideology has all the answers or does right 100% of the time with regard to every issue. It might be time to say, every once in a while, that maybe, just maybe the other side has a point with regard to certain issues. There is wisdom and humility in an ability to acknowledge one’s own shortcomings, blind spots and flaws. There is bravery and integrity in being able to step outside one’s self or one’s political affiliation every once in a while. This is not compromise; this is balance.

But we’ve lost our sense of balance, and after balance is lost, footing is sure to follow. Have we already lost our footing? Are we already tumbling down into the abyss?

It’s a lonely and often sad place to be, but I’ve grown grateful these past few months for my impulse to avoid extremes and to value the vantage point of seeing both sides. There is a lot to be learned from the margins, and from the spaces and silences between words and sentences. Endless media declarations of breaking news often are the antithesis of this idea. They seek to fill the silence with moral certainty, enabling and emboldening the clutching of extreme ideas on both sides. Rather than looking to what is there, they often spin words and events just enough to impose their own ideas and agendas onto the situation they claim to describe honestly. We reject the fullest version of the truth in exchange for clips and soundbites that affirm a viewpoint to which we already pay allegiance. We learn very little from this method. We build ourselves up higher and higher with the continued assurances and affirmations that we, and only we, are right — that we, and only we, know what is truly going on in this country.

Our arrogance is astounding. And it is dangerous. I can’t help but think of the biblical King Nimrod, his Babel tower tumbling down in the wake of ego, arrogance and certainty pushed to its extreme.

Are we next? Will the tall tower of American exceptionalism fall? It’s already crumbling, decaying around the edges and through the root. But it doesn’t have to be this way. It’s true that a single solution won’t repair the damage, but we have to start somewhere. Perhaps we start by listening, and by backing down from our positions of moral certainty and our hatred of differing viewpoints. Perhaps we do a little bit of midrash.

The loudest voices are not always the most authentic voices. I wonder what would happen if we moved to the margins and the borderlands, if we started to pay more attention to the words and deeds of those who don’t most readily appear in our social media newsfeeds because we have curated them carefully to reflect our own biases. I wonder what would happen if we didn’t immediately ridicule and silence the voices of those who see the world from a different vantage point. And I wonder what would happen if we put a moratorium on moral certainty?

Things can be better. But it’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of listening.

Monica Osborne is a scholar of Jewish literature and culture. She is the author of “The Midrashic Impulse and the Contemporary Literary Response to Trauma.”