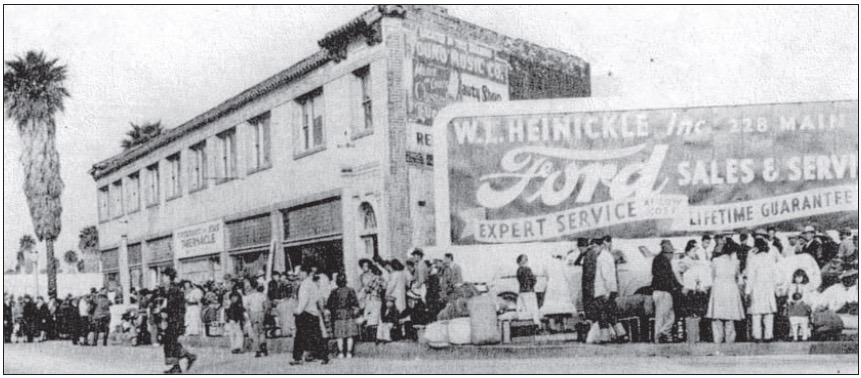

Japanese Americans line up on Venice Boulevard in Santa Monica on April 25, 1942.

Japanese Americans line up on Venice Boulevard in Santa Monica on April 25, 1942. February 19, 1942. A day that will live in infamy. The call came to round up thousands of men, women, and children, citizens of a country that no longer believed them capable of loyalty to the homeland. They were pulled out of homes, schools, and work, quickly assembled at meeting points in their cities, and then abruptly sent off to concentration camps. In justifying the act, national officials spoke of the group in racial terms, as distinct and inferior to the majority white population.

A mere month after Nazi and German leaders met in Wannsee to decide on the contours of the Final Solution, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, beloved hero of American liberals and progressives, issued Executive Order 9066 granting the right to military commanders to designate special areas from which any person could be excluded. The chief target of the Order were Japanese Americans, who, in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 9, 1941, came to be regarded as hostile aliens, even those born in the United States. Over a hundred thousand people of Japanese origin were forcibly interned in in dozens of camps from Arkansas to California, most notably in our state’s annals, Manzanar. The United States Supreme Court, when called upon to assess the constitutionality of the Executive Order, ruled in a notorious judgment that the threat of espionage outweighed the individual rights of the Japanese American defendant, Fred Korematsu, who had refused the order to move to an internment camp

Seventy-five years ago, this country’s political and military leadership targeted a group that was neither disloyal nor hostile, as previously suppressed intelligence reports have since borne out. It is hard not to think of the echoes of this ignoble moment in American history when considering the current administration. Notwithstanding his rationalizations to the contrary, President Trump’s Executive Order of January 30, 2017 is directed chiefly against a single group, Muslims.

But there are differences between then and now. Unlike FDR, Trump has a long history of baiting the group whom he seeks to stigmatize and exclude. And unlike in FDR’s time, the American judiciary today has so far proven its unwillingness to succumb to fear-mongering and discrimination. In the Korematsu case, both the federal district court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals stood on the side of the government against Korematsu, laying the ground for the Supreme Court’s memorably bad ruling. Later judicial observers regard the Korematsu as a gross miscarriage of justice. Even the arch conservative jurist Antonin Scalia declared in 2014 that “the Supreme Court’s Korematsu decision upholding the internment of Japanese Americans was wrong,” though he warned that “it could happen again in war time.”

By contrast, in the current instance of Trump’s Executive Order, both the district courts and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals have shown an unwillingness to submit to the President’s whim. They have issued a temporary restraining order against the ban on residents of seven Muslim countries. In one particularly clear-headed ruling, federal district court judge Leonie Brinkema declared that the state of Virginia has produced “unrebutted evidence” that the Executive Order was based not on national security concerns, but on “religious prejudice” toward Muslims. In response, the President is due to issue a revised Executive Order in the coming days.

In light of these developments, it is important to recall the Korematsu case as a precedent to be avoided. Jews, in particular, have a particular obligation to do so. In the first instance, remembering is a Jewish moral imperative. The historian Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi recalls that the Hebrew word for “remember”—“zakhor”—appears 169 times in the Bible, reflecting the centrality of memory in the world of the ancient Israelites. Indeed, memory has been the portable homeland of the Jews, to modify a well-known phrase.

It is important that Jews remember the past, especially in the face of resurgent expressions of antisemitism in our midst. But it is not enough to remember only the Amalekites and other enemies that have plagued our own history. The Jewish historical experience, during which our forebears were frequently cast as alien and hostile to their host societies, has imposed an added obligation to call attention to the injustices inflicted on others. This legacy of discrimination and persecution meets up with the Biblical mandate to defend the rights of the orphan and widow and to love the stranger (Deuteronomy 10: 18). As a group that was subject to stigmatization in and exclusion from many countries, including the United States, Jews have a responsibility to recall the black spot of Japanese American internment. Similarly, we have a responsibility to stand in vigilant opposition to attempts at stigmatizing or excluding groups that have become fodder for Trump’s toxic xenophobia, beginning with the Muslims targeted in his Executive Order. If Jews do not learn from the past, who will? If not now, when?

David N. Myers is the Sady and Ludwig Kahn Professor of Jewish History at UCLA.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.