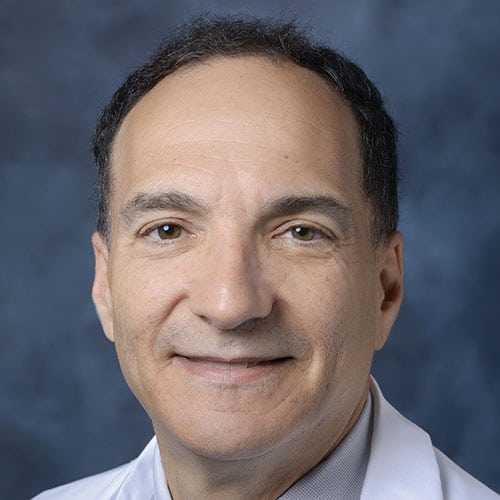

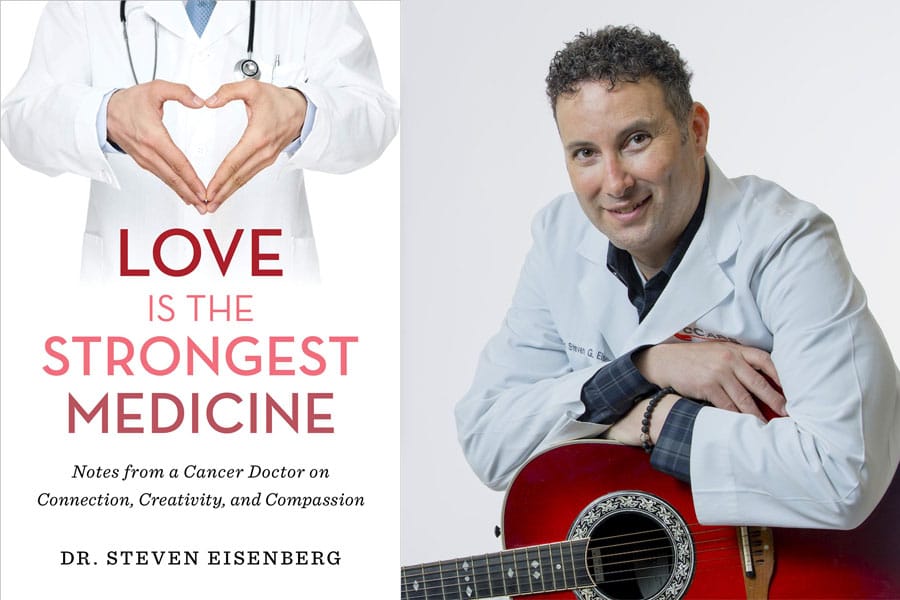

“Love is the Strongest Medicine” offers a revealing and intimate view of Dr. Steven Eisenberg’s two decades in oncology practice and traces the emergence of his unique persona: “the singing doctor.” A vivid storyteller, Eisenberg introduces us to a world of personal and medical challenges through his own story, interspersing it with the emotionally moving stories of numerous patients suffering from an eye-opening array of malignancies and attendant personal conflicts.

As an internist and geriatrician, I also inhabit the capricious world of medical illness revealed by Eisenberg. I have found that for some people, the flame of life burns so vigorously that it seems inextinguishable. For others, even young people, it can prove tenuous and at constant risk of flickering out. Tending the flame is never more dramatic than in oncology: the stakes are high and the margin for error, or even bad luck, is frighteningly narrow. Eisenberg possesses a gift for gleaning meaningful lessons from this high stakes arena. As we all eventually deal with illness and the inevitability of death, the lessons offer relevance beyond the world of cancer.

Tending the flame is never more dramatic than in oncology: the stakes are high and the margin for error, or even bad luck, is frighteningly narrow.

Eisenberg’s story begins at age 13 with a nearly fatal bicycle versus station wagon accident that set the stage for his medical career and teaches him about his own and others’ vulnerability as well as the value of compassionate care. The close call also provided a heartfelt personal lesson that he passes on both to patients and readers: don’t ever take life for granted. Indeed.

Eisenberg takes the reader through the challenges of medical school and the hazing-like rites of passage in his oncology fellowship at Georgetown University Hospital. There, the center’s arts and humanities program encouraged him to explore creative modalities to connect with his patients. He relates the story of “Ken,” a leukemia patient whose favorite song was “What a Wonderful World,“ and how singing the iconic tune together during a painful bone marrow extraction eased the procedure for both doctor and patient. Sharing music with patients turned out to be the most important of several modes used by Eisenberg to connect with patients on a deeper level. He tells the story of Janet, a pediatrician with stage IV metastatic cancer, enjoying her life to the fullest, to emphasize the need for cancer patients to grasp each moment, regardless of their prognosis. He also draws from the story of a patient who was a Buddhist monk to remind us to “be here now,” a lesson worth considering even for those in robust health.

Eisenberg’s transition from his Georgetown training to a private San Diego oncology practice was not a smooth one. He relates that the stresses of a productivity-based pay plan—caricatured as “eat what you kill”—created stress that distracted him from patient care and contributed to a series of personal maladies including asthma, migraines, insomnia and ulcerative colitis.

The potential conflict between the finance of medical practice and devotion to clinical care challenges many physicians, myself included. Even when intentions are altruistic, every practice must earn enough to pay its employees and keep the lights on. Eisenberg notes that when he joined colleagues in establishing cCARE, his current practice, his stress abated and his health issues improved. It’s likely that greater independence played a role in the abatement of his symptoms. Closer attention to the health practices he encourages for his patients—meditation, nutrition, personal connectivity—may also have proven important. Whatever the cause, the ultimate basis for Eisenberg’s apparent resolution of the issues is left as subject for speculation.

“Love is the Strongest Medicine” focuses intently on intense solo interactions between Eisenberg and his patients. This particular kind of one-on-one care is fading in American medicine as more team-oriented approaches take hold. As an internist, I refer patients to oncologists like Eisenberg for cancer care. They continue to have hypertension, diabetes, asthma, and other active medical matters that I manage in coordination with the oncologist. Eisenberg never mentions his interactions with either primary care doctors or the infectious disease specialists, cardiologists, and others that contribute to his patients’ overall care. A bit more attention is given to allied health providers such as nurses and pharmacists, though they remain firmly in the background. The relative merits of a more team-centered approach is debatable. Yet, one cannot help wondering whether Eisenberg’s own array of illnesses might have evolved differently were others sharing the burden of care.

Eisenberg’s singular devotion to each patient creates a world populated by the oncologist, the patient, the patient’s family, and the disease. Like all medical practices, this world is influenced by many externalities. The availability and the nature of health insurance towers above all others. Eisenberg recognizes this reality in his story of Clara, an undocumented and uninsured woman with Ewing’s sarcoma, an aggressive tumor that is rare in adults. Eisenberg labels the care system “ugly and embittering” for the obstructions it poses for the uninsured. His ultimately successful struggle to provide life-saving care to the embattled 20-year-old is one of the book’s highlights. Yet, Eisenberg does not comment on the tens of millions who are not undocumented and yet still lack basic coverage.

Like me, Eisenberg must encounter many more such patients without medical coverage. Prior to the protections of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) I assume that he also encountered desperate patients asking him not to record a diagnosis on their chart in the hope that they would not lose coverage. Eisenberg rightly encourages us all to take appropriate measures to protect our future health. Securing health insurance, for ourselves and others, belongs among those measures. That our wealthy society, an outlier among developed nations, fails to provide coverage for cancer victims and others deserves more than mere passing acknowledgment. Politics, like chemotherapy, often generates strong adverse reactions. An oncologist should not be too faint-hearted to deal with either.

Eisenberg maintains a clear and intense focus on both the individual patient and the reader. That intimacy and the many hopeful tales are particularly valuable for patients embarking on cancer treatment and for affected families. As he notes, with one third of Americans expected to encounter an invasive cancer diagnosis at some point in their lives, the population at risk is large and growing. Those facing cancer, like others, would benefit from seizing the day, living the moment, and connecting with friends and family to create meaning in their lives. On that note, the singing doctor is pitch perfect.

Daniel Stone is Regional Medical Director of Cedars-Sinai Valley Network and a practicing internist and geriatrician with Cedars Sinai Medical Group. The views expressed in this column do not necessarily reflect those of Cedars-Sinai.