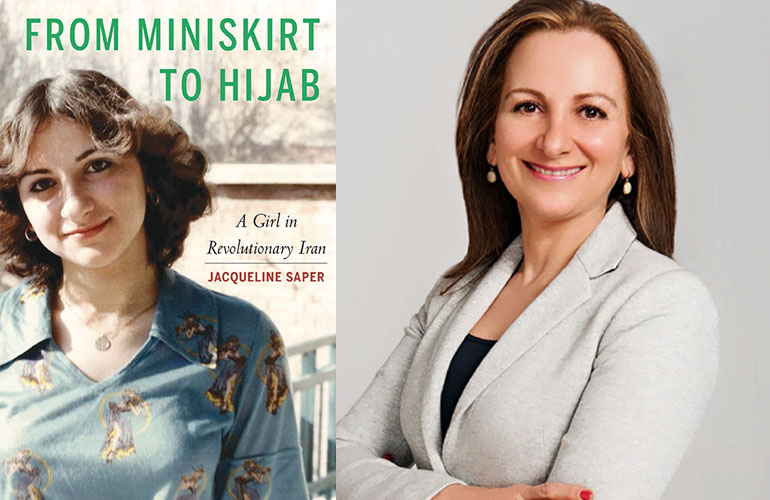

Jacqueline Saper photo by Beking Joassaint

Jacqueline Saper photo by Beking Joassaint On December 31, 1977, President Jimmy Carter stood before the Shah of Iran during a state dinner in Tehran and declared, “Iran, because of the great leadership of the Shah, is an island of stability in one of the most troubled areas of the world.” The following August, the CIA informed the president that “Iran is not in a revolutionary or even a ‘pre-revolutionary’ situation.”

But for millions of Iranians, including 17-year-old Jacqueline Saper, the reality on the ground was starkly different.

“President Carter had not walked the streets of Tehran like I had,” Saper writes in her memoir, “From Miniskirt to Hijab: A Girl in Revolutionary Iran” (University of Nebraska Press-Potomac Books, 2019). “He had not ridden in a taxi and listened to the driver’s complaints. He had not had lunch with the University of Tehran students expressing anti-Shah rhetoric. Iran was not an ‘island of stability’ (as Carter had fawned), but a land of warring values poised on a fault line.”

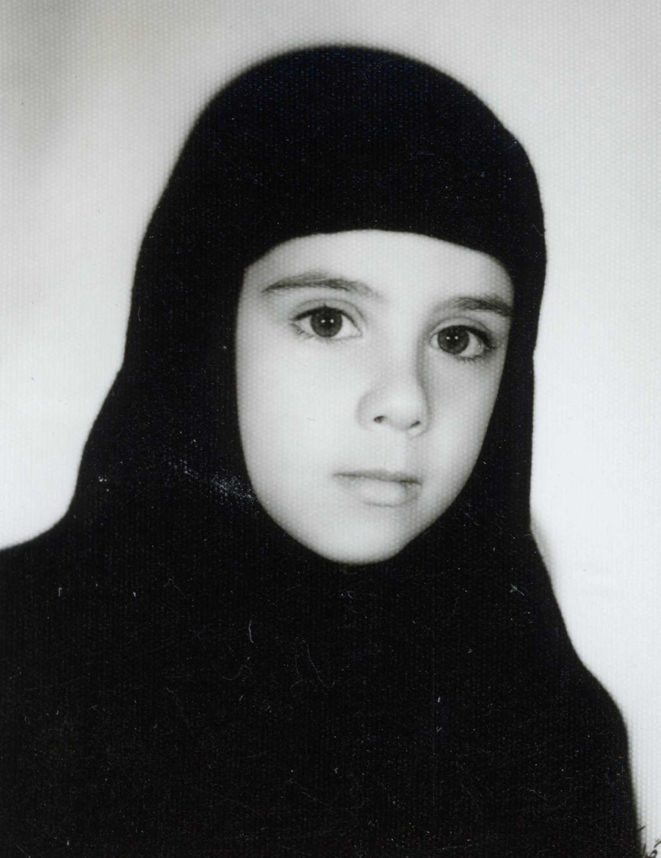

Only one year after Carter’s famous remarks, in January 1979, the Shah and his family fled Iran, and the country succumbed to the fanaticism of the Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers. They radically changed Iran into an official Shiite theocracy that enforced sharia law, including the hijab, or Islamic headscarf, which became mandatory for women of all faiths, young and old.

Other memoirs have been written about life in post-revolutionary Iran, including ones by prominent Iranian Jews living in exile in the West. Saper’s, however, is different because Saper herself isn’t your typical Iranian author.

Born to an Iranian Mizrachi father and an English Ashkenazi mother, Saper is what Iranians refer to as doerageh (“from two distinct nationalities”). Her parents’ marriage was an unimaginable rarity in 1950s Iran (her mother, Stella Averley, moved from London to Tehran and married her father, Rahmat Lavi). “As a Jewish doerageh in a Muslim society, I was a minority within a minority,” she writes.

There’s something else different about Saper: Unlike me, she wasn’t born into the Islamic Revolution; in fact, she spent some of her happiest years in Iran before the revolution. And unlike my mother, Saper wasn’t a middle-aged woman when tumult erupted in the country. Saper was eighteen and in the prime of her life — old enough to be aware of the surrounding instability yet too young to have her youth hijacked by the new regime’s tyranny. And at the tender age of 19, when the Iran-Iraq War broke out, Saper was already married and had a baby girl (she met and married her husband, Ebi, when she was 18).

“I experienced Iran in its three distinctive eras: a teenager in the monarchy, an adult during the revolution and a wife and mother in the Islamic Republic,” Saper told the Journal.

It’s not every day that you’re able to review the memoir of someone who attended your former school. It’s even rarer that the school is back in Iran. Like me, Saper attended Ettefagh School in Tehran, famously located across from the University of Tehran. Iraqi Jews founded the school decades earlier. In the 1950s, Saper’s father served as a teacher and principal of the school.

Only four months apart in age from the crown prince, Reza Pahlavi, Saper grew up in the northern Tehran neighborhood of Yousefabad. Her father was a well-respected professor who taught chemical engineering at two prestigious universities. He also worked part-time for Iranian Jewish businessman and philanthropist Habib Elghanian. Worldly and sophisticated, Saper’s mother worked for an airline company. Unlike most Iranian Jews, Saper grew up being privy to the middle-and upper-class lives of fellow Jews and the pious (and often poverty-ridden) world of lower-class Muslims. The family’s four consecutive live-in maids — devout Muslim women who lived in southern Tehran — offered her a glimpse into a world against the Shah’s obsession with turning Iran into a secular, Westernized state.

“As a teenager with deep Iranian roots, I felt the tremors of unease,” she writes. I knew and loved citizens who belonged to two different worlds, separated by an uncrossable boundary. I learned about the opposing values that affected our daily lives, causing resentment and dividing Iran.” As a young girl, Saper knew that one of those maids was in a polygamous marriage.

“From Miniskirt to Hijab” won the Chicago Writers Association 2020 Book of the Year Award for traditional nonfiction. The memoir is also a finalist for the 2020 Clara Johnson Book Award and a finalist for the 2021 Feathered Quill Book Award and has received rave reviews.

Saper has divided the book into five parts: “Hope,” “Fear,” “Adapt,” “Veil” and “Resolve.” Some exceptionally titled chapters, such as “Cracks Along the Avenue,” illustrate how the Iranian revolution wasn’t an overnight coup or quick upheaval. Instead, the process was the slow and steady result of years of resentment by religious and anti-Western individuals.

Saper spent every summer with her maternal family in England. One September evening in 1978, her older sister, Victoria, called from Iran with an ominous message: “Jacqueline, listen to me. Don’t come back. I can’t say much over the phone, but things are rapidly changing here… the Jewish community is alarmed.” That event turned out to be Black Friday, the name given to September 8, 1978, when pro-Shah forces shot and killed hundreds of people in Tehran’s Jaleh Square. But Saper returned to Iran — only to find Tehran under martial law. A few weeks later, her high school shut down. Graffiti declaring “Marg bah Shah!” (Death to the Shah) was seemingly everywhere.

Nearly one year later, as Saper was window shopping in Tehran, she heard the violent chants of “Death to America” as angry mobs approached the American embassy and took dozens of Americans hostage. She shrewdly refers to such fanaticism as “the ecstasy of dissent.”

On February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran after 15 years of exile. Schools and universities reopened, and Saper noticed that most of her classmates and teachers had fled Iran. The new textbooks praised martyrdom and demonized the West. Saper was shocked to see that there were only a few Jewish students left in her class. “Most of the Jewish teachers were also missing, and the Jewish principal of our school had been replaced by a Muslim woman who wore the hijab,” she recalled. Her history teacher taught that religion and governance were inseparable, and her Persian literature teacher told students to write about how the Islamic revolution had been a gift.

To read Saper’s vivid descriptions of such incidents is to gain a tremendous appreciation for the precious power of storytelling. The book serves as a critical primary source for anyone who’s ever wanted to know what life was like in one of the most volatile countries in the world — a land of magic and misery, where modern propaganda tars ancient tales, where “modesty police” sniffed a woman’s neck for any traces of perfume and where owning VHS tapes of foreign movies became an act of great rebellion.

“From Miniskirt to Hijab” will leave readers with the ability to understand the deeper issues related to post-revolutionary Iran. Simply put, anyone who wants to understand the human element behind American policy vis-à-vis Iran should read (and quote) this book, which should be read widely in college classrooms, among other places.

Anyone who wants to understand the human element behind American policy vis-à-vis Iran should read (and quote) this book.

The memoir also provides crucial context for the modern question of whether anti-Zionism is a form of anti-Semitism. In a decades-old televised interview, Ayatollah Khomeini famously said, “We know that the Jewish community and the Zionists are different from each other…the Zionists are not Jewish. They’re political people who commit actions under the pretense of Judaism. The Jewish people themselves hate the Zionists. In fact, all human beings hate the Zionists.” Over 40 years ago, Khomeini attempted to separate Zionists and Jews so could he pathologically vilify the latter but purportedly leave the former alone. Today, many anti-Zionists, including those in America, have followed his lead. Saper, however, considered Israel her “third homeland” after Iran and England. Once she realized the dangers of being associated with Israel in Iran, even its culture, she helped her mother break all their Israeli music records.

Just months after the revolution, Elghanian was arrested and charged with spying for Israel and “friendship with the enemies of God” (Elghanian had given to many Israeli charities). A firing squad shot him to death on May 9, 1979. Elghanian was the first Jew to be killed in post-revolutionary Iran, and the news devastated Saper’s father.

Saper’s ability to recall minute details of events and conversations is spellbinding, whether she describes how a table was set or the 2,500-year celebration of the Persian Empire in 1971. For their part, Saper’s mother and father believed that turmoil was all part of living in the Middle East. Her father continued to insist that such instability would soon pass, though his wisest advice was rooted in the reality of the region: “Never get involved with authorities in this region of the world,” he astutely warned.

Such advice proved invaluable when a female modesty enforcer in Tehran confronted Saper for not wearing the hijab. “You bloody whore!” the woman yelled while she searched Saper’s handbag. “You deserve to be treated as a sex object for men.”

In an age when the rights of women worldwide have never been more critical, Saper shines a subtle but brilliant light on a particular plight that has ravaged Iran for 42 years: the harassment of women… by women, most notably, the dreaded modesty enforcers who continue to confront “immodest-looking” women, harassing and sometimes even arresting them.

Saper’s astute observations about the nuances of the mandatory hijab in Iran are of critical importance to anyone committed to women’s rights. She rightly observes that whereas we consider the hijab today as a sign of traditional piety, on the eve of the Iranian revolution, it actually symbolized rebellion against the establishment (in this case, the Shah). She writes, “Until this period of revolutionary fervor, I had rarely seen women or girls wearing thick large headscarves that covered part of their faces. Traditional women had been content with wearing the chador, but now covering heads and wearing loose clothing had become an expression of rebellion.”

On March 7, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini announced that women should cover their hair in the workplace. It was only a matter of time before the hijab became mandatory in all public spaces, and the gap between religion and politics was irrevocably closed. Soon, street chants morphed from “Marg bar Israel” (Death to Israel) and “Marg bar Amreeka” (Death to America) to “Marg bar bi-hijab” (Death to those without the hijab”).

Buses became segregated, so that men stood in the front and women were forced to stand in the back. The warning, “Sister, guard your hijab,” was ubiquitous. Saper recalls passing a large street banner that read, “If a woman shows one strand of her hair, in her afterlife they will hang her from that same strand of hair.”

After marriage, Saper moved from Tehran to Shiraz, where her husband was a surgery resident at Shiraz (formerly known as Pahlavi) University. Ebi treated thousands of wounded soldiers of the Iran-Iraq War who were airlifted from the battlefields. Like her maternal relatives, who endured the London blitz in the 1940s, Saper soon found herself forced to survive through all-out war. During nightly air raids by Iraqi warplanes, she slept in a full hijab in case she had to run out of the house in the middle of the night.

Saper knew she needed to leave Iran, but the regime had placed harsh restrictions against Jewish families, often separating them so they could not leave the country together.

Once she realized that her daughter, Leora (age six), was shouting death chants in her first grade class in Shiraz, Saper’s mission to leave the country became clear. “During recess,” Saper writes, “Leora and her friends would play a game where they formed a funeral procession and carried an object over their heads pretending it was a martyr being taken to the cemetery.”

After reading the book, the reader will appreciate the harrowing experience of how Saper, her husband, and two young children escaped Iran in March 1987. The family temporarily settled in Houston, where Leora shed her mandatory hijab for cowboy boots. They then settled in Chicago, where Saper could finally enroll in college at age 28. She graduated with a business degree and earned the designation of CPA (Certified Public Accountant). Her husband worked painstakingly hard to start his career over as a surgeon in America.

In 1999, Saper began teaching as an adjunct faculty at Oakton College in Des Plaines, Illinois. “I initially taught business courses, but as I became more entrenched with studying and speaking about Iranian issues, the college asked me to teach Iran’s history, culture, people and government,” she said.

Her father’s death in 2014 prompted Saper to write her memoir, as she realized that precious family stories were at risk of being lost. “My children and grandchildren deserved to know about our family’s history and what happened,” she said. “As my children grew up, I realized they knew nothing about our past family history, their childhood or their ancestral homeland. [And] my granddaughter would grow up knowing nothing about her grandparents’ story.”

Today, Saper’s daughter is a lawyer and her son is a doctor. She wants to write a second book about “the unusual union” between her mother and father. “In telling their love story, I will study Jewish ethnic diversity and Jewish intra-marriage that was an unheard-of phenomenon in the Iranian Jewish community of 70 years ago,” she said.

She still remembers the fanatic street chants of those who welcomed Khomeini and the Islamic Revolution over four decades ago: “Esteglal, azadi, Jomhuri-e Islami!” (Independence, freedom and an Islamic Republic!). Her memoir provides irrefutable evidence of the tragic irony that the third call to action (an Islamic Republic) resulted in the demise of independence and freedom.

More information about Jacqueline Saper may be found on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, or at https://www.jacquelinesaper.com/

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer, speaker, and activist.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.