On June 11, 1980, Walter Cronkite ended the “CBS Evening News” with a painfully powerful message: “And that’s the way it is, Wednesday, June 11, 1980, the 221st day of captivity for the American hostages in Iran.”

Cronkite first added a count to his famous signoff to recognize Day 50 of the Iran hostage crisis, and finally ended it with Day 444, on Jan. 20, 1981, when the hostages were released.

In a 1980 editorial in The Washington Post, Ellen Goodman called the nightly count “the most powerful subliminal editorial in America,” which “has become a flag at half-mast … the closing hymn passes through our minds quickly like a flashcard — do something! do something!” For Goodman and many Americans, Cronkite’s words were a reminder of America’s impotence.

The Iran hostage crisis dominated the news. Time magazine’s 1979 “Man of the Year” was none other than the fanatical Ayatollah Khomeini, supreme leader of the newly formed Islamic Republic of Iran.

For the millions of Americans who were born after the Iranian Revolution, including myself, ignorance about such a critical event in American history is a dangerous liability. We need a refresher course on what happened 40 years ago.

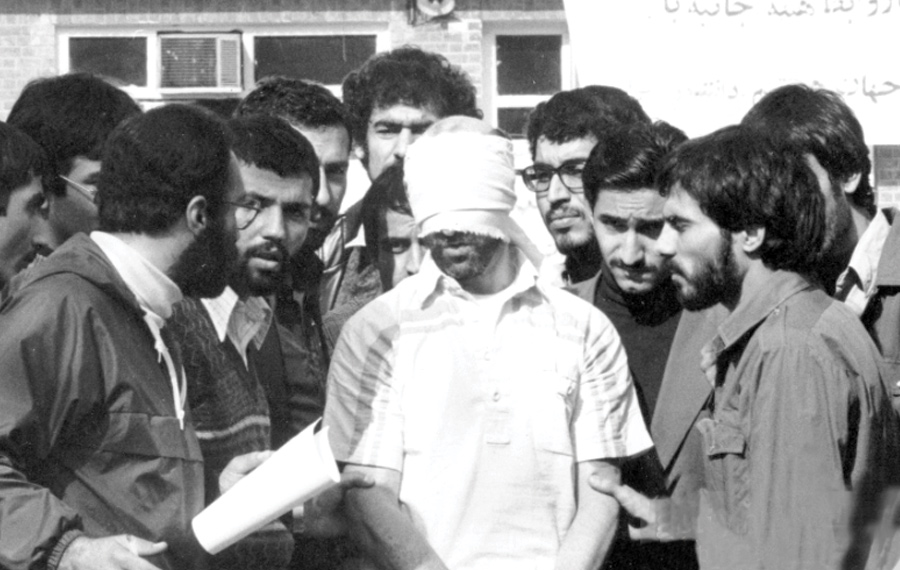

On Nov. 4, 1979, radicalized students, with Khomeini’s “blessing,” stormed the American embassy in Tehran and took everyone hostage, eventually releasing a few, including some of the women, as a symbol of “the special place of women in Islam,” and African Americans, in a show of solidarity with “oppressed minorities.” In total, 52 people were held hostage for nearly a year and a half, and several were tortured.

The Iran hostage crisis was the first world event to play out daily in millions of Americans’ living rooms, so there was even more at stake for everyone involved, including Khomeini and President Jimmy Carter. In April 1980, a U.S. Armed Forces mission tried to rescue the hostages but failed when one of the helicopters crashed, killing eight servicemen. Americans had been mesmerized by Israel’s daring 1976 hostage rescue in Entebbe, and were demoralized that the U.S. couldn’t even save its own people. For Carter, it was an unparalleled public humiliation. For Khomeini, a propaganda master, it was an act of divine intervention from “the angels of Allah” to protect the new theocratic regime.

While censoring the press at home, Khomeini understood with calculated brilliance the power of the American media. Outside the embassy, was a carefully staged media circus, which explains why Goodman asked in 1980 whether the media had “reported” on the Iran hostage crisis or helped “create it.”

The Iran hostage crisis was America’s first real experience with fanatic, politicized Islam.

After ABC and CBS refused Iranian offers to interview hostages, NBC aired a controversial interview with one hostage — Marine Cpl. William Gallegos — in the presence of his captors. Many Americans were repulsed. House Speaker Tip O’Neill said he couldn’t believe that the network had allowed Gallegos to be “trotted out” in front of the cameras. Today, the media actually seem to fight over who wins the big “get” with murderous tyrants, and Iranian leaders seem to have their pick of national dailies to publish their propagandistic op-eds.

The hostage crisis was also America’s first real experience with fanatic, politicized Islam. Before 1979, American officials were predominantly concerned with the Cold War. Weeks before the hostage crisis, when American diplomats in Iran warned of a potential attack against the embassy, officials in Washington, D.C., dismissed their concerns.

The Brookings Institution noted that the hostage crisis “set the emotional and psychological context among Americans for nearly everything that was to come between the United States and Iran.” This included two major facts that came to light 40 years ago and which still reverberate today: Iran’s revolutionary leaders are rational, pragmatic survivalists, and American-led sanctions work.

The crisis also forced tens of thousands of Iranian Jews to realize they had no future in post-revolutionary Iran, although it’s one of the greatest tragedies of my generation that many young Iranian American Jews still don’t ask questions about the tidal wave of events that forced their families out after 2,700 years.

Finally, the Iran hostage crisis taught American leaders that in the Middle East, symbolism is everything.

Ever wonder what happened to the American Embassy in Tehran? It’s still there, but Iran changed its name to the “U.S. Den of Espionage,” and it’s now an Islamic museum, open to tourists. Every Nov. 4, fanatics gather there to scream “Death to America!” This year, the delightful protesters were a group of brainwashed schoolgirls who yelled curses against America, coincidentally within perfect range of the media.

And how’s this for symbolism: President Carter worked right until his last hours in office to release the hostages, and though I don’t respect him for many reasons, it was Carter who negotiated the hostages’ freedom. In a stunning act of symbolism, the Iranians, who grew tired of the crisis but still hated Carter bitterly, didn’t release the hostages on Jan. 20, 1981 — Inauguration Day — until they were sure that Ronald Reagan had been sworn in as president, so as to deny Carter even one grain of victory before his presidency ended. Because the events coincided, the press naturally included the joyous news as part of its coverage of the inauguration, ensuring that millions of Americans mistakenly credited Reagan, not Carter, with the hostages’ release. Some people still think it was Reagan. In a January 2016 interview on “Meet the Press,” then-presidential candidate Marco Rubio credited Reagan with the hostages’ release.

In the end, it doesn’t matter who emerged victorious from the Iran hostage crisis. The U.S. hasn’t been able to stop the mullahs’ violent hegemony for four decades, and if the Islamic Republic lasts up to five decades (or more), the West will have to deal with Iran’s violent hegemony … plus a nuclear weapon with a message for Israel written on it in Persian. At that point, I’ll be holding my head under a pillow and frantically humming “Everything Is Awesome” (from “The Lego Movie”) over and over.

I’m kidding. I’ll enlist in the Israel Defense Forces faster than a presidential nominee running to greet babies at a rally.

As for Carter, he’s always said that he lost his re-election bid because of Iran. Ronald Reagan had it easier, at least in one way: In 1980, he succeeded the Ayatollah Khomeini in becoming Time magazine’s “Man of the Year.”

Tabby Refael is a Los Angeles-based writer and speaker.