Photo by Abid Katib/Getty Images

Photo by Abid Katib/Getty Images The change in dynamics of the political relations between Jews and Arabs in Israel is “the most fascinating aspect” of Israel’s politics today. Thus, the new Annual Assessment on the state of the Jewish People, by the Jewish People Policy Institute, summarizes a multifaceted trend that keeps Israel on its toes. Strangely, last year Israel also witnessed a violent crisis in Jewish-Arab relations in Israel, the most severe since year 2000.

Why the riots happened when Arab Israelis seem to be progressing towards better integration and a more comfortable state of coexistence? No one can say for sure, but a fast-spreading culture of violent crime is certainly a contributing factor. Israel’s Arab citizens are – on average – at the bottom of the education and income ladder. They are chronically underserved by their municipalities, suffer underbudgeting in various areas, and most notably in recent years, have to contend with a high and growing levels of crime and sectoral violence.

In 2020, the share of Arabs involved in Israeli crime was about forty percent, almost double their share of the population.

The numbers are devastating: In 2020, the share of Arabs involved in Israeli crime was about forty percent, almost double their share of the population. When it comes to the most serious crimes, Arabs are involved in more than sixty percent of murders. The annual ratio of murders among Israeli Arabs is almost 6 Murders per 100,000 citizens. And as one Arab activist commented, that’s higher than the corresponding ratio in countries known for violence such as Sudan and close to the ratio in a country like Bolivia.

Arabs are also involved in more than sixty percent of arson incidents, almost sixty percent of weapons offenses, almost fifty percent of robberies and about forty percent of extortion offenses. It is almost impossible to write with confidence how many Arabs were killed by criminals this year, because by the time you read it, the numbers will grow (As I write, the number of Arab killed in crime related incidents in 2021 was close to 90). Last Thursday, two Arab youngsters were murdered in the Sharon area. That was a merely a day after President Isaac Herzog warned of “the horrific wave of murders that befall the country in general and Arab society in particular”. He was right, it is heartbreaking.

Who’s to blame for these statistics and this reality? Here’s how politics and identity mix with analysis. Ask many Arabs, and especially their leaders, and they will blame the state for economically neglecting the Arab population. Ask the police, and you’ll hear stories about Arab leaders sabotaging any attempt to improve the situation. Ask members of previous governments, and they will say tell you that the country cannot do much for the Arabs if the Arabs do not cooperate with the attempt to tame corruption and criminals. Ask me and you will get the frustrating answer: all of the above.

For years, policing problems in Arab cities and in Arab neighborhoods were well-known but unaddressed. The government bears considerable responsibility in this matter, but so does the Arab political representation. The Arab leadership conveys conflicting messages on the issue of law and order. On the one hand, it expresses a desire for more aggressive policing in the Arab sector. On the other hand, it expresses suspicion and sometimes hostility toward the police, and frequently alleges over-policing of Arabs. Ultimately, you can’t have it both ways. Either you let the police function – or you don’t. If police commanders realize that once they operate among Arabs they will be exposed to allegations of racism, heavy handedness, bias, and will not have a strong political backing, the easy path for them is to stay away from trouble.

You might ask: so why wouldn’t the police include more Arabs as part of its law-enforcement units? The answer is: because a large share of Arabs does not wish to wear the Israeli uniform. Their society is not always welcoming to the uniformed professional.

The result is a stalemate. Everyone knows that there is a crisis. Everyone pretends to want something “done” to resolve it. Everyone looks to the others to be the one doing something. The new government, less ideological and more pragmatic than previous coalitions, could turn its focus to the issue. But it relies on a fragile coalition, and hence, can do nothing that could complicate the ability of its Arab members to keep supporting it. Arab Knesset Members, now in the coalition, have the power to demand more funds and resources. But no one trusts them to also support the policy once the police begin to clash with violent elements in Arab towns.

Still, if you’d want this article to end on an optimistic note, remember that crisis sometimes presents an opportunity. A justified panic over the potential severity of the situation could motivate the leadership to make a more determined effort toward a life without violence.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Here I will share paragraphs from what I write in Hebrew (mostly for themadad.com). Last week I published the full list, from best to worst relations, of US Presidents and Israelis PM’s. Here’s what I wrote about the current duo after their first meeting, and the top two couples:

A relationship is built over time, and out of dealing with common challenges. How many of these will Biden and Bennett have? It is not clear. Clinton and Yitzhak Rabin had a significant joint project that occupied both of them. George W. Bush and Ehud Olmert had a short but close relationship. In the parade of couples – who are the presidents and the prime ministers who got along best with each other – it seems to me that these two couples are on top. Itzhak and Bill, George and Ehud.

A Week’s Numbers

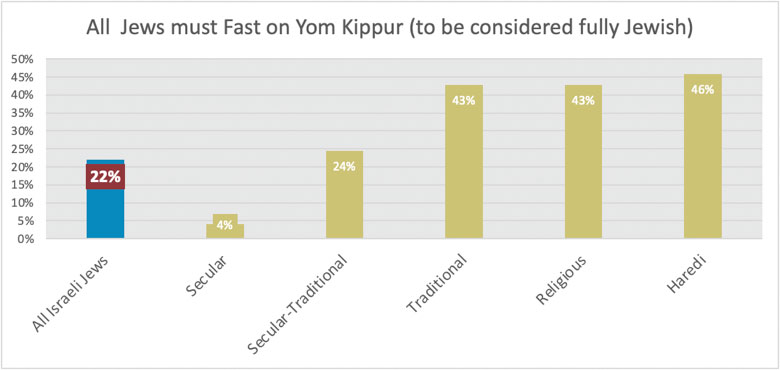

The Who is a Jew project of TheMadad.com asked what “all Jews must do (and if they don’t then they are ‘less Jewish’)”. One of the options was “fast on Yom Kippur”. As you can see, most Israeli Jews (two thirds of which fast on Yom Kippur), would not make this practice a conditional test of Jewishness.

A Reader’s Response:

Commenting on my conversation on Rosner’s Podcast with historian Andrew Porwancher, about the possibility of Alexander Hamilton being Jewish, Mitchell Barak wrote the following (on Facebook):

“My understanding is that Hamilton’s mother’s husband Johann Michael Lavien was of German origin…. If her [Hamilton’s mother] husband was not practicing and did not live as a Jew, it seems unlikely that his estranged Scottish wife would adopt such practices. On the other hand, if Lavien was Jewish, his wife would have had to convert before marrying him under Danish law at the time. I think the only thing we can say is there is not enough record to say definitively either way.”

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.