When Cedars-Sinai Medical Center OB-GYN oncologist Dr. Beth Karlan was a student at Harvard University in the early 1980s, she was doing her rounds and presenting the case of a Jewish woman in her 30s who had ovarian cancer. The woman suddenly sat up and pointed a finger at Karlan and said, “What right do you have to stand there and pursue your dreams to become a doctor and I’m going to sit here and die?”

It was one of those seminal moments that helped lead Karlan down the path to a career in OB-GYN oncology. “I went into [the field] almost as a challenge because of that young woman,” Karlan said. “It’s the Yom Kippur question of who shall live and who shall die, and it really challenged me. ‘Why did she have this ovarian cancer and I didn’t?’ ”

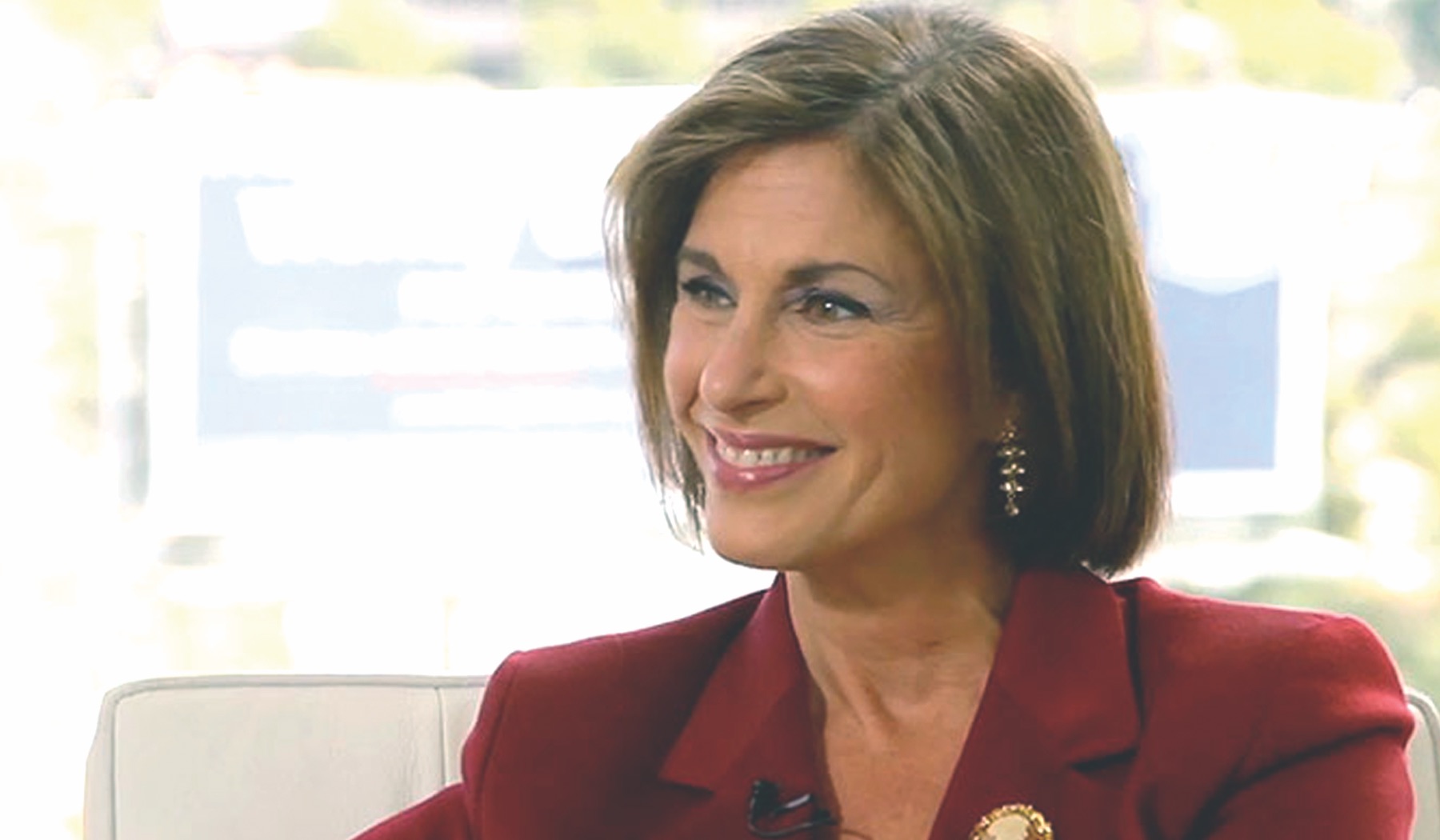

Today, as director of the Cedars-Sinai Women’s Cancer Program at the Samuel Oschin Comprehensive Cancer Institute, and after decades of research, Karlan has just launched the BRCA Founder Outreach Study (BFOR), which is offering BRCA genetic testing at no cost to 4,000 eligible men and women, ages 25 and older, of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish ancestry.

The pilot study is being launched in New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Los Angeles, and each city is looking to sign up 1,000 participants. According to research, Jews of Ashkenazi descent are 10 times more likely to carry the BRCA1 and BRCA2 inherited gene mutations than the rest of the population, which can lead to breast, ovarian and other cancers.

“Knowledge is power. [BFOR testing for Ashkenazi Jews] could save your life.” — Dr. Beth Karlan

As Karlan progressed in her career, she began to recognize family clusterings in OB-GYN oncology. “I would see these clusterings of sisters whose moms had died,” she said.

Karlan also treated Gilda Radner, who died of ovarian cancer in 1989, and she launched the Gilda Radner Hereditary Cancer Program in 1991. The BRCA1 gene would not be discovered until 1994, with the BRCA2 gene being discovered a year later.

“As the BRCA genes were discovered, our lab continued to work on what goes awry in a cell due to a mutated BRCA gene,” Karlan said.

She is excited about the launch of the BFOR study, which has been two years in the making. The Ashkenazi Jewish mutation for BRCA1 and BRCA2 is a “founder mutation,” Karlan explained. “When a population stays relatively insular, any genetic alteration will be amplified within that population.”

The outreach part of the BFOR program is designed to let Ashkenazi Jews know this testing is available through a simple blood draw. “It’s also about letting people decide if they want to participate and what it means,” Karlan said.

What does it mean?

“It’s letting people know that men are equally likely to carry a BRCA gene as women,” Karlan said. “That they too are at risk for cancers, and that there are things they can do to reduce those risks. [It’s letting them know] not everybody who has a BRCA gene gets cancer, and that if you do have the gene, you should let your family members know.”

Karlan said it’s estimated that 90 percent of carriers don’t know they are until someone in their family gets cancer. “But for every carrier we identify, 50 percent of their blood relatives will also be carriers.”

Outreach also includes access to educational videos, signing a consent form and filling in a family history. Participants must be at least 25 years old and have one grandparent of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

If people choose to go ahead with the free testing, the blood draw will be done at a Quest lab and then they can choose to receive their results from their medical provider or from one of the geneticists involved in the study in their home city.

The BFOR testing “lets people who may be afraid or may not have had the resources get the education and then have the results disclosed by a medical professional,” Karlan said, adding, “Knowledge is power. It could save your life.” While discovering new cancer treatments is always a great thing, she said, “What’s better than a new treatment and cure is prevention.”

As a result, Karlan said if the BFOR test comes back positive, there are plenty of things people can do to lower their risk of getting cancer. For women with the gene mutation, their risk of getting breast cancer is five times greater than the population’s, with an 80 percent chance of getting it in their lifetimes. “Depending on your family history, you should be screened with both MRI and mammography, and there are medications you can take to reduce the risk,” she said.

The risks of ovarian cancer in those with the gene mutation is 20 times that of the general population, Karlan said. “If women act, their overall risk can be reduced by over 80 percent. Some of these preventative methods include taking birth control pills, or having their fallopian tubes removed, because it’s thought most of these cancers arise in the fallopian tubes,” she said, noting that women can still have children through in vitro fertilization even if they have their fallopian tubes removed.

Other risks of being a carrier include melanoma, “so you can go to a dermatologist and have your skin tested,” Karlan said. There are also higher risks of pancreatic cancer, and screening can be done for that, too. For men, there is an increased risk of pancreatic cancer, melanoma, breast cancer and prostate cancer.

Karlan said she believes her secular Jewish upbringing informed her decision to help people. “I grew up in New York and tzedakah and tikkun olam were in my DNA. It’s part of our core values of who we are as people.”

She recalled an ongoing joke in her home when she was growing up on Long Island. Her father, who was an attorney, worked in Manhattan near Wall Street and would need a new coat three or four times every winter. “My mother would say, ‘Stanley, are you crazy? You’re losing your [coats]!’ But he’d see someone homeless on the street and give them his coat.”

As the first physician in her family and the oldest of three girls, Karlan said her decision to become a doctor had a lot to do with the fact that her father always wanted to be a physician but there was no night school that he could attend. “And I also had a crush on Dr. Kildare,” Karlan said, laughing about the TV character played by Richard Chamberlain.

The first female oncology fellow at Cedars-Sinai, Karlan has been at the forefront of a lot of firsts. She was the only female in her medical school class at Harvard MIT, and throughout her career “there were times you learned to work harder,” she said. “To be accepted, you had to do better. You learned to have a thicker skin. When I was doing a surgery rotation, men were surprised I could stand in the operating theater for long hours. They’d say to me, ‘Are you tired? Do you need to sit down?’ Or I’d come out of the [operating room] and they’d say to me, ‘Who picks up your dry cleaning?’ ”

But her hard work has paid off. Now, she’s focused on the BFOR study and hopes those who fit the criteria will consider taking part in the study.

“I urge people, as we approach Pesach and celebrate our freedom, that they recognize that knowledge discovery is part of that, and it may be a good time to think about family history, to think about things that run in your family and ways to make the world a better place by keeping people healthy.”

To learn more about the BRCA genetic mutation testing, visit bforstudy.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.