Ever since Joseph, coat torn, was tossed into that fateful pit by his brothers in the book of Genesis, the Twelve Tribes of Israel have never fully reconciled. Benjamin, Naftali, Issachar, Judah and Co.’s descendants squabbled over subsequent biblical books, leading to a divided Israelite kingdom shortly after the reign of King Solomon. Ten of the tribes were exiled by the Assyrians during the 8th century BCE and lost to assimilation within the vast empire. Only two – Judah and Benjamin – remained as identifiably Israelite over subsequent centuries.

Tradition believed that should those lost Ten Tribes be found, the reunification would signal the start of the Messianic Era.

A long-forgotten theory, unmentioned in the latest debate over Christopher Columbus’ Jewish origins, is that with the discovery of the Americas, the hope quickly emerged that the New World’s Natives might in fact be these long-vanished Jews.

In 1650 in Spanish and two years later in English, the popular Amsterdam-based Rabbi Menasseh ben Israel published his book “Mikveh Yisrael” (“The Hope of Israel”). It reflected the Messianic hopes swirling in his time, spurred in the Dutch Republic as Ashkenazi Jews reunited there with their once-distant Iberian Sephardic coreligionists. As Lipika Pelham has written, ben Israel’s community, inspired by the coming together of those who had been apart for centuries, believed that “perhaps the Jewish wandering, the aspiration of the previous Diasporas, had reached its completion. The next and final step would be the Jews’ return to the land of their ancestors.” In “Mikveh Yisrael,” ben Israel cites the findings of a crypto-Jew named Antonio de Montezinos, whom he had met. The itinerant Portuguese-born Montezinos claimed to have bumped into members of the tribe of Reuben in the northern Andes, in modern-day Colombia after escaping the Inquisition in 1639. In his travelogue, he recounted how these Natives could recite the Shema prayer in Hebrew and told him, much to his surprise, “‘Our Fathers are Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob’ … then they joined Reuben adding another finger to the former three” that they had lifted up in counting off their biblical-era ancestors.

Enthralled by this discovery, Rabbi ben Israel saw prophetic potential. After all, he claimed, once Jews settled in the corners of the world, the Messiah would swiftly arrive, based on the verse in Deuteronomy, “Then the Lord will scatter you among all the nations, from one end of the earth to the other.” Ben Israel even used this argument to encourage the Lord Protector of the British Commonwealth Oliver Cromwell to allow the exiled Jews back into England. After all, England, “land of the angles,” was believed to be one such corner of the globe. The country’s name in French translates to Angleterre – end of the land.

Ben Israel wasn’t alone in his belief, as the Americas had sparked millennial expectations in Christianity as well. As the historian Elizabeth Fenton has documented in her “Old Canaan in a New World,” the Puritan Edward Winslow, in his 1649 work “The Glorious Progress of the Gospel Amongst the Indians in New England,” saw his community’s role in spreading their faith to the Natives as helping them return to their biblical roots.

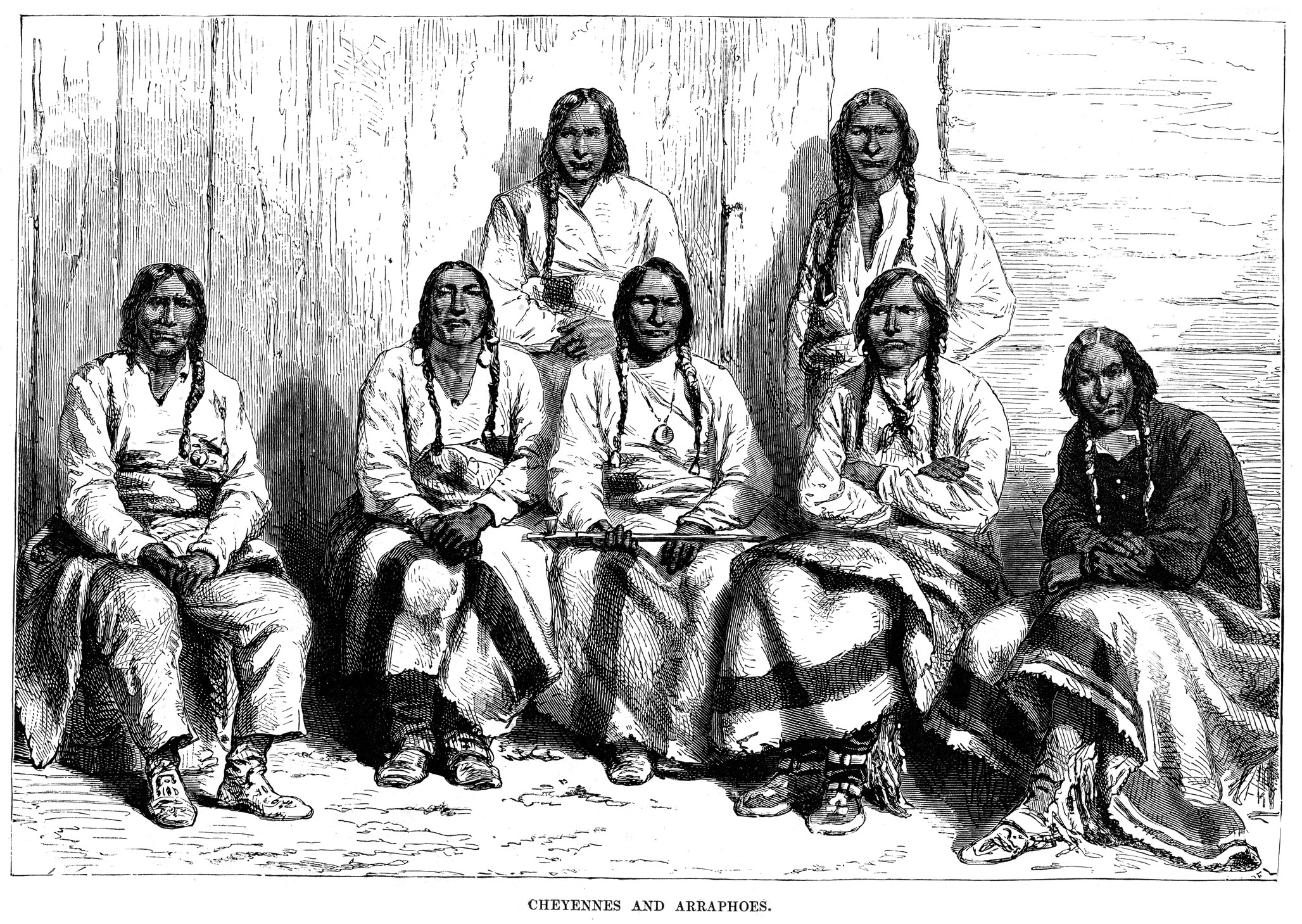

Roughly a decade later, the English Presbyterian minister Thomas Thorowgood published a similarly-minded tract, “Jews in America; or Probabilities, that those Indians are Judaical.” It was inspired by Rabbi ben Israel’s writings. He listed, among other purported commonalities: “They constantly anoint their heads, as did the Jews … They delight exceedingly in dancing … eate no swines flesh tis hateful to them as it was among the Jewes” (sic) and “The Indian women are easily delivered of their children, without Midwives, as those in Exod. 1.19,” a reference to Shiphrah and Puah’s explanation to Pharaoh as to why they hadn’t killed Jewish male babies in the delivery room. Alas, the Judaic origins of the Natives weren’t necessarily to their credit. “The Jews were a sinful people,” Thorowgood wrote, “the Indians were and are transcendent sufferers.” It would be, in his opinion, Christianity that would redeem them.

The Hebraic Indian theory was considered by Thomas Jefferson in a letter to John Adams. Jefferson mentioned that he had read a work by the historian James Adair that “believed all the Indians of America to be descended from the Jews: the same laws, usages, rites & ceremonies, the same sacrifices, priests, prophets, fasts and festivals, almost the same religion, and that they all spoke Hebrew.” Jefferson cautioned, however, “his book contains a great deal of real instruction on its subject, only requiring the reader to be constantly on his guard against the wonderful obliquities of his theory.”

Adair’s book, “The History of the American Indians,” had been published in 1775, based on the recommendation by Benjamin Franklin to the publisher. Its support for the Judaic origins of the Indians included claims such as the Natives calling God “Yohewah,” which sounds like the ineffable name of the Jewish God, and the “Cheerake” (sic) observing the biblical law of offering cities of refuge to accidental murders “so inviolably; as to allow their beloved town the privilege of protecting a wilful murtherer.” Adair also noted what struck him as observance of the “Mosaic laws of uncleanliness,” with women separating themselves from their husbands for a certain period every month, and “their frequent bathing, or dipping themselves or their children in rivers, even in the severest weather,” which, in his opinion, “seems to be as truly Jewish, as the other rites and ceremonies which have been mentioned.”

The theory was taken so seriously that the Founding Father Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, acting as a medical advisor to the expedition of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant William Clark in 1803, supplied the adventurers with a list of exploratory questions, including “What Affinity between [Native American] religious Ceremonies and those of the Jews?”

Other Christians saw in the Native tribes not lost Israelites but to-be-defeated Canaanites, from whom the Children of Israel had conquered the Promised Land. In a representative example, Yale College president and Congregationalist minister Timothy Dwight IV, in his 1785 poem “The Conquest of Canaan,” described the mission of the Christian Americans to subdue the native pagan peoples through the biblical prism of Israel’s defeat of the also-pagan Canaan.

Nineteenth century America’s most famous Jew held firm to his hope that the Hebraic Indian theory was true. In 1837 the former diplomat, popular playwright and journalist Mordecai Manuel Noah published “Discourses on the Evidences of the American Indians Being the Descendants of Lost Tribes of Israel.” In it he listed as supporting evidence “their belief in one God,” “the computation of time by their ceremonies of the new moon,” “their divisions of the year in four seasons, answering to the Jewish festivals of the feast of flowers, the day of atonement, the feast of the tabernacle, and other religious holydays,” “the erection of a temple after the manner of our temple, and having an ark of the covenant, and also the erection of altars,” and “the division of the nation into tribes with a chief or grand sachem at their head.”

Nineteenth century America’s most famous Jew held firm to his hope that the Hebraic Indian theory was true.

Noah concluded: “… in their daily prayers and sacrifices, in their festivals, in their burials, in the employment of mourners, and in their general belief, I see a close analogy and intimate connection, with all the ceremonies and laws which are observed by the Jewish people; making a due allowance for what has been lost, and misunderstood, in the course of upwards of 2000 years.”

A few years earlier, Noah, embracing America’s emergence as a land premised on biblical covenants, had attempted to build a homeland for the Jews in upstate New York. He invited the nascent Jewish community to join, alongside their coreligionists in Europe, who, Noah believed, would come to escape European antisemitism. They would be joined by, naturally, the Native Americans. In language echoing ben Israel’s two centuries before, he proclaimed, “If, as I have reason to believe, our lost brethren were the Ancestors of the Indians of the American Continent, the inscrutable decrees of the Almighty have been fulfilled in spreading unity and omnipotence in every corner of the globe.” If all these scattered Jews could come together on his island near Buffalo, “what joy to our people, what glory to our God, how clearly the prophecies have been fulfilled … how providential our deliverance.” Alas, nothing came of Noah’s initiative, and Jewish national renewal would have to wait until 1948.

By the second half of the 19th century, as the U.S. hurtled towards the Civil War, national interests had swayed from pondering the potential ancient origins of the land’s original settlers. The whereabouts of Israel’s Ten Tribes settled back into the sands of history. But at least for a time, Americans had believed that Naftali and Issachar’s descendants could be found right next door.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”