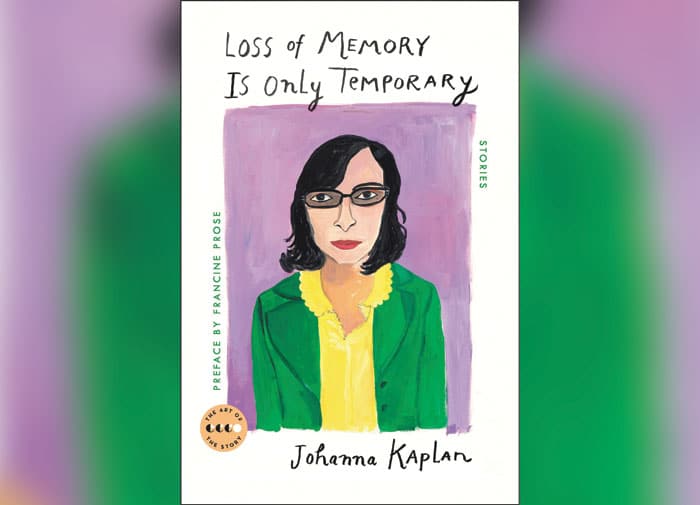

Forget judging a book by its cover: one look at the facial expression on Johanna Kaplan’s author picture on the back flap of “Loss of Memory is Only Temporary” will give a reader everything they need to know about this book. The Maira Kalman drawing on the front is fabulous, too (like everything the genius cartoonist creates), but Kaplan’s face, tilted slightly toward the camera, below salon-perfect white hair, is a wry, sardonic, “you can’t be serious” fisheye. It’s a look I recognize—my teenager wears it all the time. Who knew it would suit an eighty-year old so well?

It’s a look I recognize—my teenager wears it all the time. Who knew it would suit an eighty-year old so well?

Kaplan might not be a household name for all readers, but she’s certainly a writer’s writer. She’s been a finalist for the National Book Award, the American Book Award, and the Hemingway Foundation/PEN Award, and she won the National Jewish Book Award for Fiction (twice), the Kenneth B. Smilen Present Tense Literary Award, and the Edward Lewis Wallant Award. Cynthia Ozick is a fan. Francine Prose is a big fan. Prose, who introduces this collection, claims she’s carried Kaplan’s “Other People’s Lives” (first published in 1975) from one end of the country to the next, repeatedly; it’s a book she can’t live without.

“Loss of Memory is Only Temporary” is essentially a reprint of “Other People’s Lives” as it includes the six stories from that collection (“Other People’s Lives,” “Sickness,” “Sour or Suntanned, It Makes No Difference,” “Dragon Lady,” “Babysitting,” and “Loss of Memory is Only Temporary”) with two more pieces: “Family Obligations” (first published in “Forthcoming” in 1983) and “Tales of My Great-Grandfathers” (published in Commentary in 2000). The former, following a female physician in the Polish-Soviet War, evokes Isaac Babel’s “Red Cavalry” (with the addition of a backtalking American teenage grand-niece showing up later in the story), and the latter is an autobiographical essay that speaks beautifully to Kaplan’s writerly raison d’être, what she calls her “nistar family,” the hidden family and peoplehood that nourish her imagination.

If you just want to read about people being mean, sarcastic and obnoxious to each other in the funniest ways, you have come to the right place. Make yourself at home.

Now back to that fisheye. On the one hand, if you are coming to this collection looking for stories that have clear beginnings, middles and ends, or ones that are plot driven, and in which a lot happens, you will be disappointed. Sometimes things happen, but more often than not, they happen in a character’s head. If you are coming to this collection, on the other hand, looking for an uncanny and hilarious performance of the way people (by “people,” I mostly mean Jews) talk at each other (never to, only at) or for the observations of people who are, on the outside, quiet and remote, though in reality incredibly insightful, or, finally, if you just want to read about people being mean, sarcastic and obnoxious to each other in the funniest ways, you have come to the right place. Make yourself at home.

Personally, my favorite story is “Sour or Suntanned, It Makes No Difference.” The main character here is a teenage girl who has been sent off to sleepaway camp, where she is generally miserable. Miriam is a city girl, so “what she would do with a bunch of trees, Miriam did not know.” She is told she’ll meet kids from all over, but as far as she can tell, the furthest they come from is Teaneck, New Jersey. Miriam is from the Bronx as is Bryna Sue, but Bryna puts on airs because she’s from Riverdale, a posh section of the borough. She says it’s practically the countryside. Miriam has no patience for this claim. “Where you live is the Bronx,” Miriam tells her. “On your letters you put Bronx, New York.” Bryna Sue tries to argue that she could write “Riverdale-on-Hudson” as her address instead. Miriam: “You could … but it would probably end up in a museum in Albany.” I am imagining Miriam making the same facial expression Kaplan does on the back flap of the book.

The story takes place around the late ’50s—in other words, not many years after the Holocaust—and we can infer that the parents of the campers are either survivors or family members of those who perished. For Parents Day, the campers are made to put on a play that they themselves don’t understand; it’s in Yiddish. The play is about the Warsaw ghetto, and it consists of almost everybody dying. “My part’s good,” Miriam declares, “I’m practically the only one who doesn’t turn out to be killed.” The irony of the story hinges on the children’s failure to recognize the impact of a play of this nature, for this audience, at this time. Miriam is more focused on her mother coming up to camp, seeing how lousy it is, and taking Miriam home with her than she is on the play. Yet her observations about the play and everything else suggest an innate intelligence, an ability to see things for what they are. Explaining her role in the play to Bryna, Miriam says she overhears Nazi soldiers drunkenly screaming out their plans and then goes back to the ghetto and warns everyone. “So the whole thing is that you copy Paul Revere?” asks Bryna. “The only kind of Paul Revere it could be is a Jewish kind,” replies Miriam. “Everybody dies and there are no horses.”

Although I was not a fan of “Dragon Lady,” which lacks the snappy language and humor of the rest, I think this collection includes some of the best Jewish American stories in print, putting Kaplan, in my opinion, both in league with her fan, Cynthia Ozick, as well as the queen of Jewish dialogue herself, Grace Paley.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.