David Steinberg started his career as a stand-up comedian in 1968 and achieved the distinction of 140 appearances on The Tonight Show during its golden age under Johnny Carson. He moved into a parallel career as a director of comedy shows ranging from “Designing Women” to “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” and he has engaged in an on-going public conversation with fellow comedians as the host of the long-running documentary series, “Inside Comedy.”

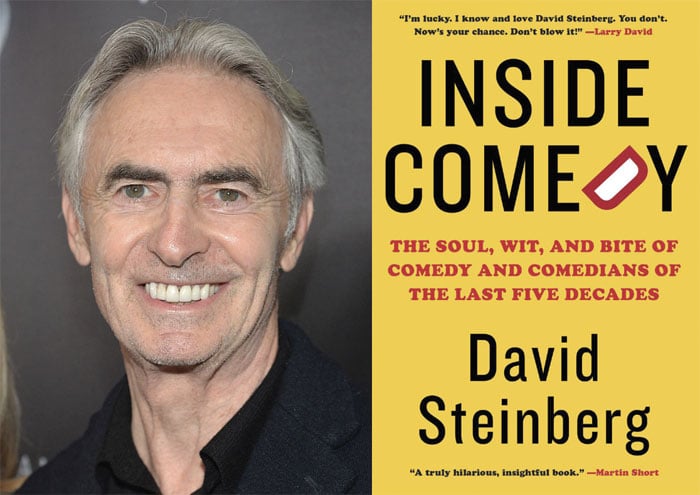

Steinberg uses the same title for his new book, “Inside Comedy: The Soul, Wit, and Bite of Comedy and Comedians of the Last Five Decades (Knopf), which is both an frank and intimate memoir and, almost coincidentally, a sweeping history of contemporary American comedy. More often than not, when Steinberg drops a name, it’s someone he knew before he or she was famous. Not unlike Steinberg’s on-stage and on-screen persona, the book is funny, savvy and thought-provoking, all at the same time.

We learn, for example, that he was a pre-rabbinical student at Hebrew Theological College before taking the stage as a stand-up comedian for the first time in 1968 at the Bitter End in Greenwich Village in 1968. His set included comic sermons based on the Bible, his first comedy album was titled “The Incredible Shrinking God,” and he cracks that his familiarity with the Talmud meant he had “the only little black book in Hollywood that was written in Aramaic.”

Steinberg learned a crucial lesson about stand-up he saw Lenny Bruce for the first time at the Bitter End, a jazz and comedy club in Chicago. “He was a revelation because he wasn’t trying to be funny all the time,” Steinberg recalls. “Doing comedy was being smart, which I saw with Lenny. I suddenly knew that I wanted to be smart as much as I wanted to be funny. And then I realized that being funny is a version of being smart.”

Indeed, Steinberg is credible both as a comic and as an intellectual. For example, he was introduced to the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer by Philip Roth while a student in the class that Roth taught at the University of Chicago. Years later, it was Steinberg who introduced Barbara Streisand to the Singer’s work, which is why she ended up directing and starring in a motion picture version of “Yentl.” By then, Steinberg and Singer were lunch buddies.

But Steinberg is not merely name-checking his fellow celebrities. He recalls the work he did and the conversations he had with an encyclopedic list of actors and comedians — Woody Allen and Carol Burnett and Sid Caesar, Bette Midler and Mike Myers and Steve Martin, Don Rickles and the Smothers Brothers and Lilly Tomlin, Flip Wilson and Jonathan Winters and Robin Williams, among countless others. Each reminiscence carries an insight into the experiences and emotions that help to explain what made them so good at what they did (or still do).

Robin Williams, for example, was working the late-night shift at an ice cream parlor in San Francisco when he saw a flyer for an improv night at a Lutheran church. He had spent two years as an acting student at Juilliard under John Houseman but “left when Houseman told him that there was nothing more he could teach him.” The stand-up stage, rather than Juilliard and John Houseman, was what it took to launch the stellar career of Robin Williams, which Steinberg analyzes in detail and with deep compassion.

“He had an unbelievable sense of what is funny, and his mind went so fast,” explains Steinberg. “But his real genius was his improvisation—brilliant, sometimes scary, because you never knew where he was going.” What the public never saw was his generosity, and Steinberg reveals that when his classmate at Juilliard, Christopher Reeve, suffered the catastrophic injury that ended his acting career, it was Williams helped to pay Reeve’s medical bills. “That was the personal, incredible thing about Robin Williams—he had the biggest heart.”

Steinberg devotes a chapter to the Hillcrest Country Club. “For the price of a small house, you could play eighteen holes of golf there, or a game of tennis,” he writes, “but the real action was at the comedians’ table, set back in a corner of the main dining room.” Among them were both Danny Kaye (“who was Jewish despite the changed name – he was born David Daniel Kaminsky”) and Danny Thomas (who was “Hillcrest’s first non-Jewish member”). When Thomas became a member, Jack Benny quipped: “The least they could’ve done was admit someone who looked like a gentile.” Steinberg reveals that he used to chat in Yiddish with Danny Thomas, who learned the mamaloshen in showbiz circles.

“Inside Comedy” comes at a fraught moment in American comedy, but Steinberg helps us put the latest hot topic – Dave Chappelle’s “The Closer” – into its historical context: “There is no way there would be Dave Chappelle if there hadn’t been Richard Pryor.” And Steinberg himself was capable of offending his fellow Jews with his comedy. When Pryor and Steinberg were both on the bill at the same New York nightclub, Pryor asked him: “Son of a bitch, David, how come the Jews don’t get pissed at you?” Steinberg confides to us: “Not quite true. They were pissed at me.”

If there is a through-line in “Inside Comedy,” it is the struggle of stand-up comics to test the boundaries of what can be spoken aloud.

If there is a through-line in “Inside Comedy,” it is the struggle of stand-up comics to test the boundaries of what can be spoken aloud. In that sense, the current controversy over Dave Chappelle is only the latest example of the true calling of a comedian. “And now that the era of Trumpism had suddenly fallen on our heads, and as the independent press is suppressed and discredited, we needed our comedians to remind us that the emperor had no clothes,” Steinberg writes. “I should know—a big part of my early success came from satirizing Nixon and his gang, a necessary service to the nation, even though it put me on the Enemies List.”

The punchline to a famous joke about the secret of comedy – “Timing” – comes to mind in the pages of “Inside Comedy.” Steinberg makes the point that there is nothing new about the effort to stifle the stand-ups and censor their comedy, and he reminds us that perhaps never before has it been more important to push back. On that point, he quotes something that George Harrison told the Smothers Brothers when they found themselves in a battle with the network censors in 1968: “’Whether you can say it or not’ Harrison urged them on the air, ‘keep trying to say it.’”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.