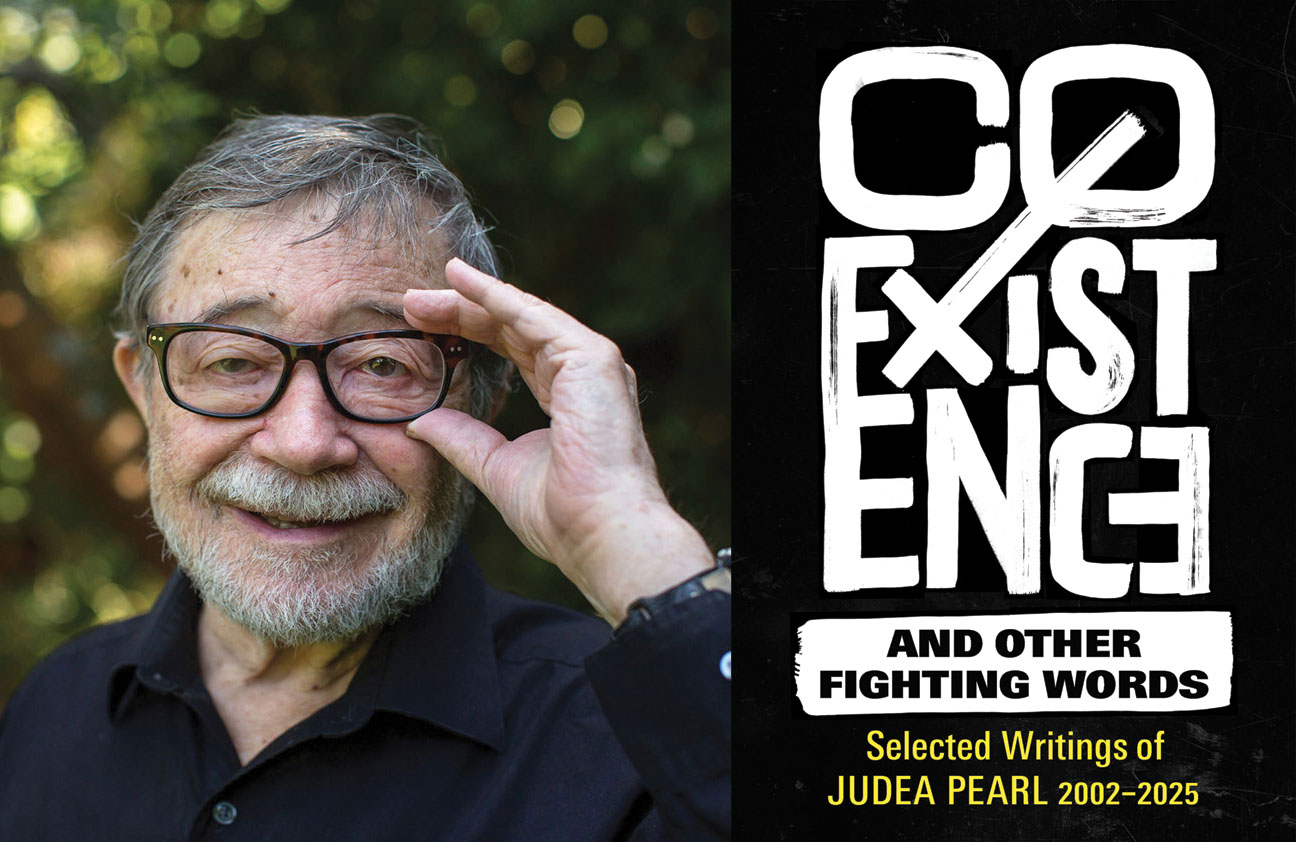

World-renowned artist and toymaker Ivan Moscovich describes himself as an inventor first and a workaholic second.

The 93-year-old, who lives in the Netherlands, has spent the past 75 years creating brain games like his globally successful board game, The Amazing Magic Robot, as well as hundreds of puzzles and artwork for people ages 4 to 104. As if that weren’t enough, Moscovich is also a renowned scientist, mathematician, author and founder of Tel Aviv’s Israel Museum of Science and Technology in 1964.

Moscovich’s artwork, which can be found in London, Berlin, Tel Aviv, Mexico City and Basel, made its Los Angeles debut June 26 at the h Club in West Hollywood, where his 74-piece kinetic art collection will be displayed and on sale for a year.

His persistence to create comes from spending the first 18 years of his life surviving the Novi Sad raid in Hungary (after the annexation of former Yugoslavian territories); two Nazi work camps; and four concentration camps including Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen.

Moscovich told the Journal that his creative abilities saved his life and, after he was liberated, he never looked back, for fear the traumas of the Holocaust would swallow him whole.

“Ever since liberation, I became a workaholic, which was basically an escape from the traumas, so therefore I had to [invent] and I did it in an obsessive way,” he said. “Workaholics — it’s a disease, it’s an illness. … This year one of my last puzzles came out and it’s probably one of my best. It is a great mathematical concept. … It’s a beautiful game. It’s called the 30-Cubed. It’s a set of 30 cubes in which you can play [an] endless number of games. You’re solving mathematical concepts through shape, color and numbers and it’s becoming a success.”

It’s a rare thing when math, science and art can blend in a fun way but Moscovich has made a career out of it.

“Creativity is the thing that joins [math, science and art] together,” he said. “I learned from my father to be creative. I didn’t have it before. [My father] was killed later by the Hungarians. Doing what I did for 75 years was enough time to make me become a creative person.”

Moscovich developed his first American invention in Los Angeles in 1965 when Mattel founders Elliot and Ruth Handler took an interest in him while he was working at the museum. They wanted to hire him to make puzzles and games.

Moscovich remembers not paying attention to them when they visited him in Israel but was shocked when, after Mattel flew him to Los Angeles, they picked him up in a limousine and sent him to Disneyland before their meeting. He was 39 at the time and thought it the height of luxury.

Moscovich said he will always remember the harrowing ride to Disneyland because his driver missed the freeway exit, lost control of the vehicle and ended up in oncoming traffic.

“It was an absolute miracle I survived,” he said. “I survived Auschwitz and concentration camps but I nearly didn’t survive that exit to Disneyland.”

But his luck didn’t end in L.A. He said he once received a fortune cookie in a Chinese restaurant here that read, “Sell your ideas. They are totally acceptable,” and he has kept that piece of paper ever since.

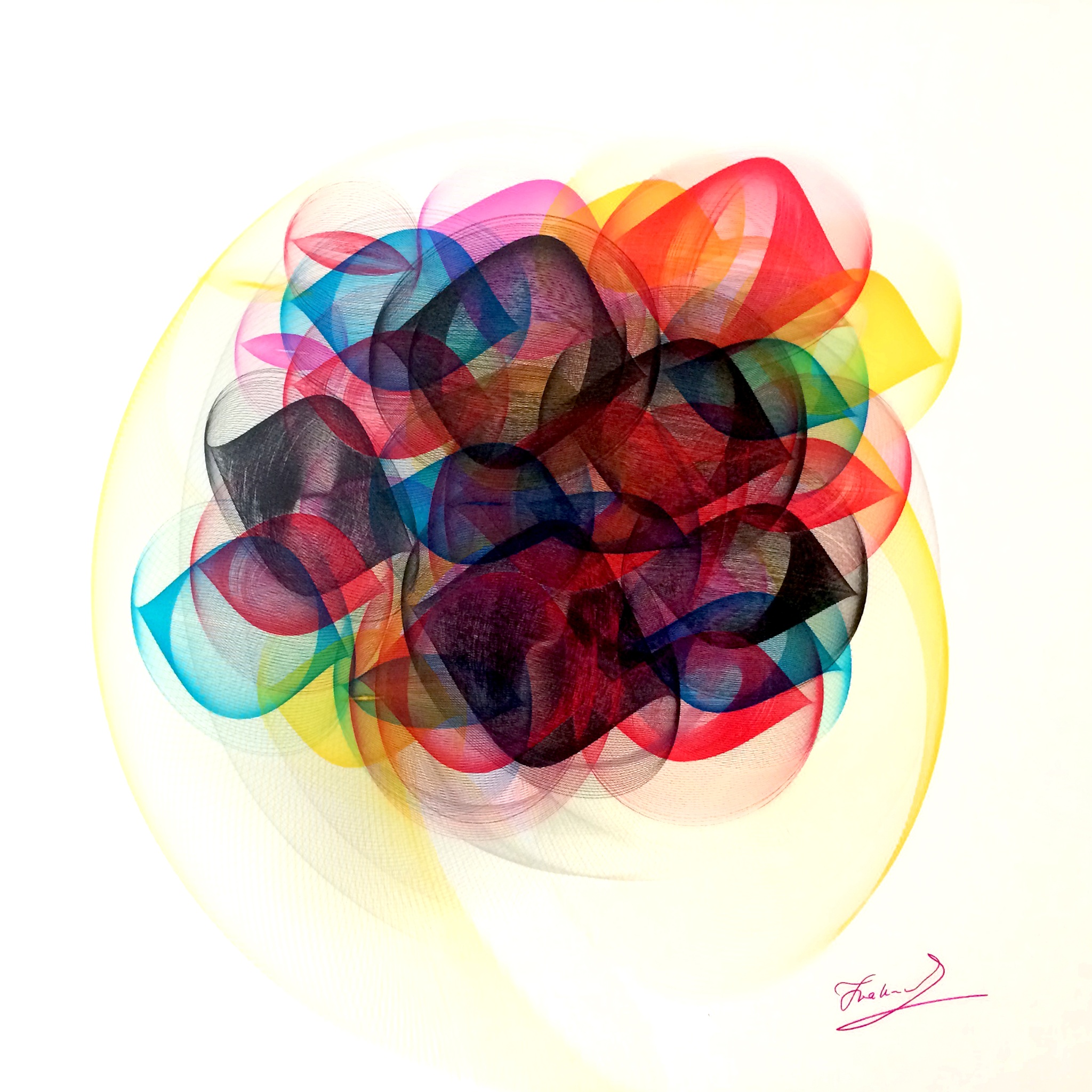

Moscovich went on to work with Mattel and later with European publishers. He sold his puzzles in “The Big Book of Brain Games” and all its editions. Then, in 1968, he decided to invent his own kinetic art. He developed and patented the Harmonograph, an analog machine that creates drawings in a pendulum motion. He has made more than 100 pieces from the Harmonograph — called harmonograms.

Moscovich said each harmonogram, just like every person, is unique. Each viewer is drawn to a different shape and color pattern. Over the years, his favorite color palettes have changed. He is currently drawn to the new black optical illusion shape he created.

“Everything is connected in the world,” he said. “The fact that I was in

Auschwitz and four concentration camps, you know, and later an inventor, it’s

fully connected.”

Like his puzzles, which can have different outcomes, Moscovich knows that his story could have also turned out very differently, perhaps like that of his idol and academic peer, Primo Levi, the Jewish Italian chemist and author who committed suicide 42 years after being liberated from Auschwitz. Levi, Moscovich posited, could not rid the traumas from his memory.

“In one of [Levi’s] books, he wrote that 40 years later, still the consequence of Auschwitz is there and quite often he is sitting with his family, playing with his children and suddenly his mind switches over to Auschwitz and is taken over with memories from [there]. … I had the same symptoms. The difference is … my mind worked to save me. I needed the escape. The escape was a workaholic game inventor, which is what I became.”

It seems the only thing Moscovich hasn’t accomplished yet is a lifetime achievement award. The British Toy and Hobby Association plans to remedy that by presenting him with one this November.

His final series of books and puzzles has just been released and is available on Amazon. He enjoys making harmonograms from his living room and spending time with his wife, Anitta, his daughter Hila, and his granddaughter, Emilia, whom he says is becoming a “workaholic actress” in London.

Now that he has achieved everything he wanted out of life, he jokes that he is “ready to die” in the best way possible: “Falling over during a mathematician’s lecture.”

To see Ivan Moscovich’s work, visit Amazon. The Museum of Tolerance is also planning a retrospective of his work.