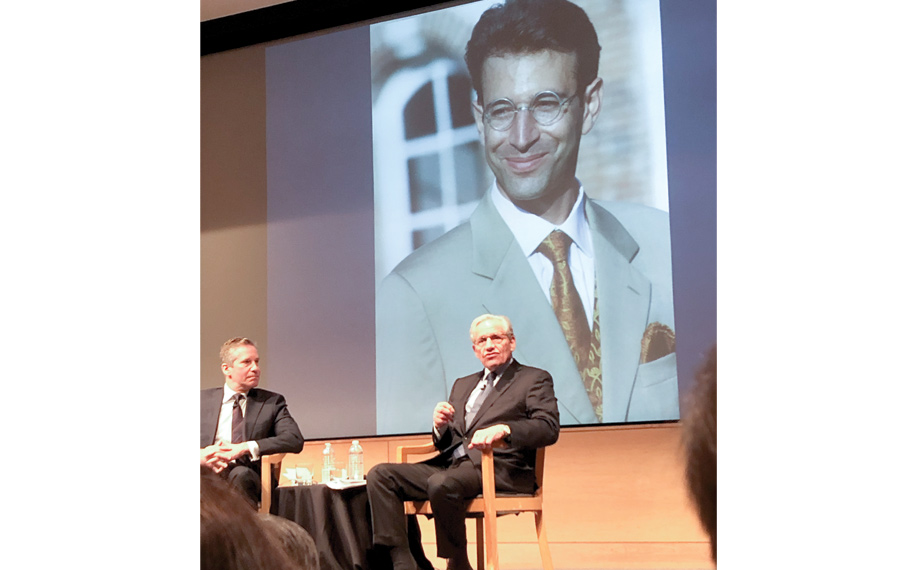

Journalist Bob Woodward,

right, interviewed by Kal Raustiala, director of the UCLA Burkle Center, at the Daniel Pearl Memorial Lecture. Photo by Yaniv Raymond

Journalist Bob Woodward,

right, interviewed by Kal Raustiala, director of the UCLA Burkle Center, at the Daniel Pearl Memorial Lecture. Photo by Yaniv Raymond “My first thought on waking up is: ‘What are the bastards hiding?’ ”

So observed Bob Woodward of The Washington Post, who exposed the Watergate scandal and triggered the resignation of President Richard Nixon by digging up what his administration was trying to cover up.

Woodward spoke recently at the Daniel Pearl Memorial Lecture, honoring the life and death of the young Jewish Wall Street Journal reporter, murdered by Islamic extremists in 2002, while investigating a terrorist network in Pakistan.

Over the past 17 years, the annual lecture, under the auspices of the UCLA Burkle Center for International Relations, has drawn an overflowing house as a crash course on the nature and pitfalls of journalism. Presenters have included such illustrious practitioners as Anderson Cooper, Tom Friedman, Ted Koppel and Larry King.

Woodward drew his No. 1 rule for good journalism from Pearl’s report on the devastating 2001 earthquake in India, reprinted in the book “At Home in the World.” As he approached a field littered with victims and noticed the smell of decaying bodies, a nearby fireman called out to him, pointing to one casualty, “Come closer, come closer and you can see his hand.”

Observed Woodward, “That’s the job of a journalist — to come closer and closer — and Danny Pearl was a master of details.” So was Carl Bernstein, Woodward’s partner in breaking the Watergate story. “Carl used to push every story to the final second of his deadline, because he felt that he never knew enough,” Woodward said.

Woodward was introduced by Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and by Daniel Pearl’s father, UCLA professor emeritus Judea Pearl, a computer scientist and considered a world-class authority on artificial intelligence.

“My first thought on waking up is: ‘What are the bastards hiding?’ ” — Bob Woodward

Although many people have written off journalism as a form of politics, Judea Pearl countered that good journalism was more important than ever. That is particularly true because “we are under siege by President [Donald] Trump and we cannot stay on the defensive,” said Woodward, whose recent book “Fear,” which is sharply critical of the White House atmosphere, has been denounced by Trump as “fiction.”

Woodward’s formula for bringing journalistic reports closer to the reader is the old-fashioned practice of speaking to interviewees face-to-face, preferably in their own homes.

For instance, as part of one investigation, he knocked on the door of a private home to talk to the four-star general inside. The general was unenthusiastic, asking Woodward, “Are you still doing this s—?” but Woodward got his interview.

In another case, the reporter called a source at 11 p.m. and when the official objected to the late hour, Woodward said he lived nearby and could be at his house in four minutes. “How do you even know where I live?” the agitated official demanded, but after Woodward showed up, the interview stretched into the dawn of the following day.

Granted, this journalistic method demands a certain amount of chutzpah and self-confidence, but gets better results than the interaction with journalists preferred by big shots.

“If you send an email to the White House saying you want a response, you will get four press secretaries trying to figure out how to write a statement that doesn’t mean anything,” Woodward said.

Here are some samples of Woodward’s advice to aspiring or practicing

journalists:

Step back from political food fights.

Don’t think too highly of yourself.

Show that you are really interested in what the other person is saying.

Don’t despise your enemies — they, too, have a human face.

Don’t speak or write with too much certainty.

To illustrate the last rule, Woodward cited his reaction to President Gerald Ford, when he swiftly pardoned his predecessor, the disgraced Nixon.

The general reaction in the media was that Ford’s move was based on some kind of corrupt bargain and would forever damage his reputation. Some 45 years later, Woodward was working on a book on the legacy of Watergate and asked Ford why he had sabotaged his own career by pardoning Nixon. Ford responded that he knew what the consequences would be of a trial that would split the country for months or years and obliterate any hope of healing the nation.

That reason, Woodward said, “was the very opposite of my earlier conception and I couldn’t get it out of my head. It took me 45 years” to revise his initial judgment.

For that reason, he concluded, “Before writing ‘Fear,’ I read everything about

what Trump had done in the first 18 months in office. I knew I couldn’t wait another 45 years to correct any mistake I might have made.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.