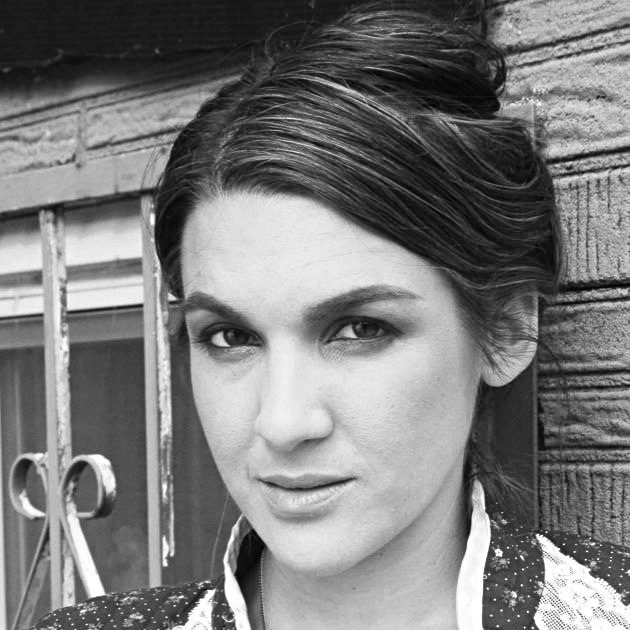

Natasha Lyonne in Russian Doll Photo courtesy of Netflix

Natasha Lyonne in Russian Doll Photo courtesy of Netflix This article contains spoilers from the Netflix series “Russian Doll.”

The new Netflix series “Russian Doll” is so splendidly Jewish.

The eight 30-minute episodes in Season 1 follow the life of the main character, Nadia, played by Natasha Lyonne (“Orange is the New Black”), who dies and wakes up at her 36th birthday party in a never-ending loop, “Groundhog Day”-style.

The series is Jewish in two distinct ways. It’s a rare combination of secular New York bagels and kosher pickles Jewish, and deep mystical and ethical principles Jewish.

On the surface, there are the trappings of the sort of Jewish history that’s threaded through the streets of the East Village: a birthday party in an old yeshiva building, now an ultra-fancy hipster loft encased in subway tile; a synagogue on 14th Street — at its center an old, bearded rabbi who was a couple of blocks away all along; and the necklace Nadia wears throughout the series, which represents not only her lost mother who left it to her, but her Holocaust survivor grandparents, who lost faith in paper money and trusted only gold currency.

As much as I love the ghost of the yeshiva, the mystical/practical rabbi and Lyonne’s representation of intergenerational trauma, I’m most compelled by the Jewish thought embedded in the plot. The idea that you can make a decision that minimizes rather than maximizes your humanity; a decision that hurts rather than helps those around you is the epitome of the Jewish concept of teshuvah. Often translated as “repentance,” teshuvah really means “returning”: returning to our best selves and the life we should be living.

Traditionally, Jews focus on teshuvah during Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, but it is an ongoing process throughout the year. The classic interpretation of teshuvah is espoused by Maimonides, the 12th-century Spanish rabbi and philosopher. I love this description of his steps to Teshuvah by Rabbi Leora Kaye and artist/animator Hanan Harchol, not least because we see Nadia precisely as a “Jew on the street,” wandering the streets of Alphabet City over and over:

[Maimonides] wrote for the simple “Jew on the street” as much as for scholars, and his codes have remained relevant across the spectrum of Jewish belief until today. According to Maimonides, four of the most important steps of teshuvah are the following:

- Verbally confess your mistake and ask for forgiveness (Mishneh Torah 1:1).

- Express sincere remorse, resolving not to make the same mistake again (Mishneh Torah 2:2).

- Do everything in your power to “right the wrong,” to appease the person who has been hurt (Mishneh Torah 2:9).

- Act differently if the same situation happens again (Mishneh Torah 2:1).

When I first encountered this text in my early 20s, I appreciated its practical advice toward righting a wrong. So much better than guiltily agonizing for years and years. But I, like many people, had a problem with No. 4. If making a different decision in the same situation is the final step, then true teshuvah is hard to come by. To really do it right, you’d have to go back to a different multiverse, be presented with the exact same situation and then make a different decision.

This is Nadia’s story. She follows Maimonides’ steps of teshuvah, one by one, multiverse by multiverse. Being human, she sometimes slips, but in general, she moves forward. She apologies to her friend for a hurtful past comment; she reconsiders her refusal to connect with her ex-boyfriend’s young daughter; on two separate occasions she makes sure a homeless man has shoes on a cold night; and eventually, she puts her heart and soul into saving her teshuvah partner, Alan (Charlie Barnett).

“Russian Doll” not only depicts the behavior of teshuvah, as laid out by Maimonides, but also moves us by showing the characters’ inner growth. Before they can complete their teshuvah and live their fullest lives, both Nadia and Alan must face the demons that led them to fail others. This is teshuvah as a therapeutic practice. When she first sees the ghost of her neglected child-self, Nadia immediately dies, but little by little she grows stronger, able to face her own trauma and let go of her guilt.

“‘Russian Doll’ not only depicts the behavior of teshuvah, as laid out by Maimonides, but also moves us by showing the characters’ inner growth.”

Sitting down to write this story, I Googled “Maimonides Russian Doll” and discovered a post on ReformJudaism.org, discussing why Maimonides called his great work of commentary “Mishne Torah,” the “second Torah.”

[Maimonides] must have seen himself as upholding the commandment [of] repeating and retelling God’s law. Maimonides’ addition to the previous replications of God’s word finally results in the textual equivalent of a Matryoshka (Russian nesting) doll, one retelling nested inside another, each one a successively larger copy of the predecessor concealed within it.

In this analysis, Torah itself — including Maimonides’ commentary — is a Russian doll; a series of self-enclosing multiverses considering the same story from a different angle.

Like Torah, the video games Nadia designs for a living are both directional (moving forward in time) and cyclical (starting over and over). So it is with life. We may not wake up over and over at the same aging hipster birthday party, but we do repeat our patterns, and we do have the ability to change our lives by shifting our attitudes, behavior and ultimately our reality.

Teshuvah is the central Jewish expression of this concept; another way of saying that perhaps there are multiverses, different possible versions of each of us. It is up to us to decide which world we will live in and who we will be.

Alicia Jo Rabins is a writer, musician and Torah teacher. Her most recent book of poetry is “Fruit Geode” (Augury Books).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.