Bela Fleck, the banjo virtuoso, continues to take the instrument most closely identified with country and bluegrass into musical realms never before explored. And the following he has built from his musical dexterity and artistic curiosity keeps him busy.

When asked what he’s been working on, Fleck reels off a dizzying list of projects: a recently completed tour with eclectic bassist Edgar Meyer; several solo concerts in the next few months (one at Carnegie Hall); shows with jazz pianist Chick Corea in the spring; completion of a live recording with Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté; shows performing his banjo concertos with classical orchestras; and periodic appearances with his wife, clawhammer banjo player Abigail Washburn — in California this month and around the country throughout 2019.

So how did a nice Jewish boy from New York City’s Upper West Side become not only a banjo player, but a banjo player in such great demand?

Fleck laughs when asked that question and has a ready answer. He fell in love with the instrument after hearing the theme to “The Beverly Hillbillies,” by the legendary guitar-and-banjo duo Flatt & Scruggs. Fleck was less interested in “the story of a man named Jed” than the picking of Earl Scruggs. “It blew me away,” he said. “I was 4 or 5 years old, and I had no idea what it was. I didn’t have any cultural point of view of what it was. It was just a sound. It jumped out and grabbed me.” From then on, he said, he was “an activated banjo person.”

“People are either banjo people or they’re not,” Fleck said, “but if you’re banjo people, you have to hear Earl Scruggs. … And whenever you hear that sound, you’re happy.”

Banjo person or not, it took a few years before Fleck actually picked up the instrument.

“I ended up learning all about the banjo and loved everything about it, but I always thought it was a lot more to it and you could do anything with it.”

“I never told anyone I wanted a banjo,” he said. “In fact, I never thought anyone could play one. It sounded so impossible to actually play. It would take incredible conceit to believe you could actually make the sounds that Earl Scruggs made.”

He asked his mother for a guitar, but it wasn’t until he was 15 that he got his first banjo. A bit of serendipity put the instrument in his hands. His grandfather — part of the family that owned the famed Junior’s restaurant in Brooklyn — had retired to Peekskill, N.Y. Coming across a five-string banjo at a garage sale, he picked it up, figuring that “Bela likes guitar, maybe he’ll want the banjo.”

When Fleck went to visit his grandfather and spotted the instrument waiting for him, it was “like hearing the sound of the angels singing,” he said. “I was so excited. Nobody knew how passionate I was about the banjo. I have no idea how that happened.” Not only that, but on the ride back home, a man asked Fleck about the banjo and whether it was in tune. Fleck had no idea, so the gentleman tuned it up and showed him a few licks — unknowingly giving the teenager a boost toward his future course in life.

Oddly enough, Fleck wasn’t all that interested in bluegrass or country, the music with which the banjo is most often associated. His musical tastes were similar to those of most 1970s teenagers, and the Beatles, the Grateful Dead, John McLaughlin, Ravi Shankar and Miles Davis were among his favorites.

“All of those things made me excited about what I could do with the banjo,” he said. “I took it very seriously. I ended up learning all about it and loved everything about it, including the bluegrass side, but I always thought there was a lot more to it and you could do anything with it.”

His musical pursuit was so unusual, however, that he often had to deal with laughter from people when he would begin to play.

Fleck discovered that playing Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven” on the banjo was a great icebreaker, and he started adapting more songs for the instrument’s singular sound. Hearing the tune “Spain” by Return to Forever — the all-star group led by Corea — sent him off looking for jazz that “had a rhythmic push to it.” He realized that any music with “the intensity of bluegrass and quick, short notes” would work.

Fleck said his family thought his choice was “kind of odd.” His mother wanted him to go to college (“so I’d have something to fall back on”), but when it was time for him to start applying to schools, she was pregnant with his step-brother (his father, who is not Jewish, left when he was a child). “They had a new baby, so they really couldn’t focus on me,” he said. He added that he didn’t mean that remark as a slight — both his mother and stepfather worked for New York City’s school system — but by the time they asked him about college, it was too late. Besides, he says, “there was never any choice for me. I was already in all different kinds of groups.”

Fleck’s desire to expand the banjo’s repertoire took him from New York to Kentucky, where he worked with musicians associated with banjo legend J.D. Crowe — “I thought that some of his traditional genius would rub off onto me” — and to numerous other places, musicians and influences around the world. “I wanted to be able to do it all,” he said.

Fleck and Washburn live in Nashville with their two children.

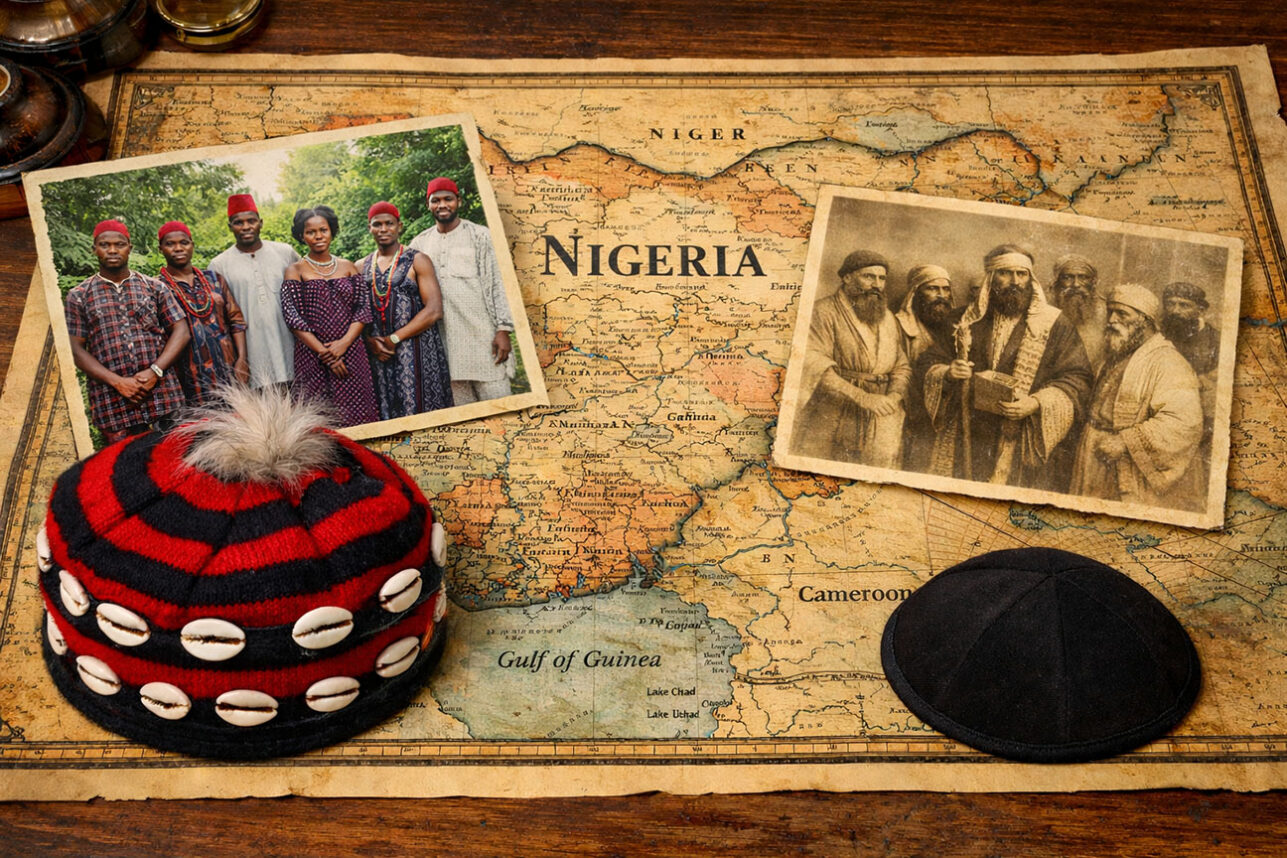

Asked if he sees his path as continuing to introduce the banjo into all sorts of 21st-century music, he responded: “That means exploring its African roots as well as exploring any modern place that I like. … I have to be learning new musical ideas, influences and sequences” to take on a particular musical project. He said he wants to “put the banjo in front of people” while also seeing what he can further discover from the instrument itself — “doing these studies from the banjo’s perspective and learning about the music from the inside.”

Fleck said that when he was growing up his family was not very observant. He has fond memories of going to temple as a child and celebrating Passover and Hanukkah, but his Judaism never went much deeper than those experiences. His mother has “rediscovered her Jewish roots,” he said, and she sent him a menorah to use while on tour. As for his own children, “It’s sort of hard for me to push it on them, because their mother is not Jewish,” he said. But I think it’s an important part of their heritage, and I’m proud to be who I am and I want them to be proud of who they are.”