The interior view of a Panoramic Sukkah. Photo courtesy of Eliyahu Alpern

The interior view of a Panoramic Sukkah. Photo courtesy of Eliyahu Alpern Can you say you love your body?

I wish I could. I’m embarrassed not to love this vessel that has served me so well.

After all, our bodies are our golden ticket to existence on this earth, the condition of our very aliveness. And yet I struggle daily, and have since I can remember. Even as a little kid, along with the joys of movement, I carried a self-reflexive disgust at my physical form.

Where does this struggle come from? Nothing particularly sets apart my body from other human bodies — a privilege in a culture where people of differing abilities, genders, sizes and races are the target of comments and attacks based simply on their appearance.

There’s no easy explanation. And yet I always have had this sense that my body overflows its boundaries, that my hunger and my shape are somehow shameful. Like some sort of spiritual radon, this discomfort leaks into every element of my relationship with this body I call home.

I don’t know why this happens — but I do know that I’m not alone. Kerry Egan, in her beautiful book about being a hospice chaplain, “On Living,” writes:

“There are many regrets and many unfulfilled wishes that patients have shared with me in the months or weeks before they die. But the time wasted hating their bodies, ashamed, abusing it or letting it be abused — the years, decades, or, in some cases, whole lives that people spent not appreciating their body until they were so close to leaving it — are some of the saddest.”

This epidemic lives deep inside so many of us. Even in those of us who truly believe that all bodies are beautiful, that sisterhood is powerful, that we must throw off the bonds of oppression.

Which raises the question: What is the medicine for this sickness? What practices can help heal us — can hold our whole bodies exactly as they are, and can celebrate our bodies in all our imperfect radiance?

Jewish tradition has an answer — accessible to all, ancient as the nomadic impulse, as basic as the need for shelter. It may be made of twigs and hay and strung-together flowers, yet it is somehow powerful enough to outlast entire civilizations.

Yes, I’m talking about the sukkah.

You gotta love a mitzvah that invites us — requires us! — to show up with our whole bodies. A practice that surrounds, embraces and sanctifies every single part of our physical selves.

The sacred thinness of the walls reminds us what it means to be cold, to feel the air on our skin, to appreciate shelter.

The roof of organic material, through which we can see the stars, reminds us that only in this particular body can we experience the universe, reminds us of how very tiny and miraculous we are.

Yes, the sukkah is good medicine.

After all, we live in a society that is synced with the mind, not the body. We are surrounded by plastic, by bleating voices that emerge from tinny speakers. Technology cycles ever faster; our glowing, hand-held rectangles connect us and distance us in the same moment.

There is a pleasure in this, to be sure, but it is a fleeting pleasure, a sugar high that dissipates, leaving us exhausted and hungrier than before. We begin to lose the pleasures of the body, pleasures of touch, smell, moon, water, earth.

Sukkot invites us back into the bodily realm. We enter a hut made of natural materials that have grown, like our bodies, from the soil. We enter an experience of time in which obsolescence is measured in millennia, not months. In this space, our body becomes the flame on a match, flaring, then gone — our time too brief to even consider despising the miraculous mechanism through which we experience God, through which we experience one another.

Some see the sukkah as a way for us to remember, culturally, the time we wandered in the desert. But as in Passover, when we are commanded to see ourselves as if we personally left Egypt, perhaps we also need to cease personally to wander in the desert. For some of us, this is the desert of struggling with our bodies.

Beneath the canopy of sky, all that limitless expanse, the sukkah shelters us.

It is, like our bodies, a temporary dwelling, beautiful and imperfect, in which we stay for a while, until we return to the earth.

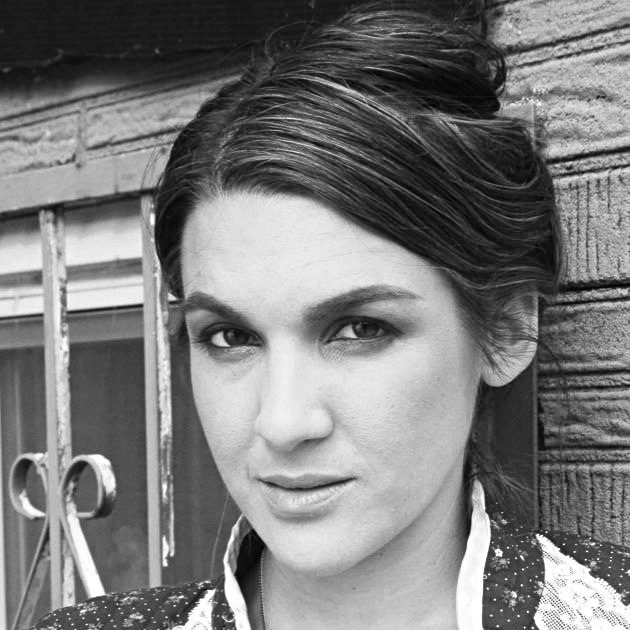

ALICIA JO RABINS is a writer, musician and Torah teacher based in Portland, Ore.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.