Gezahegn Dereve and Demoz Deboch have dreamed of making aliyah to Israel from Ethiopia for almost their entire lives.

As children, the young men moved with their families from rural villages to an Israeli government-sponsored Jewish compound in the Ethiopian city of Gondar, leaving behind everything they owned. They and thousands of other Ethiopians who claim Jewish lineage saw the journey as a first step toward making aliyah.

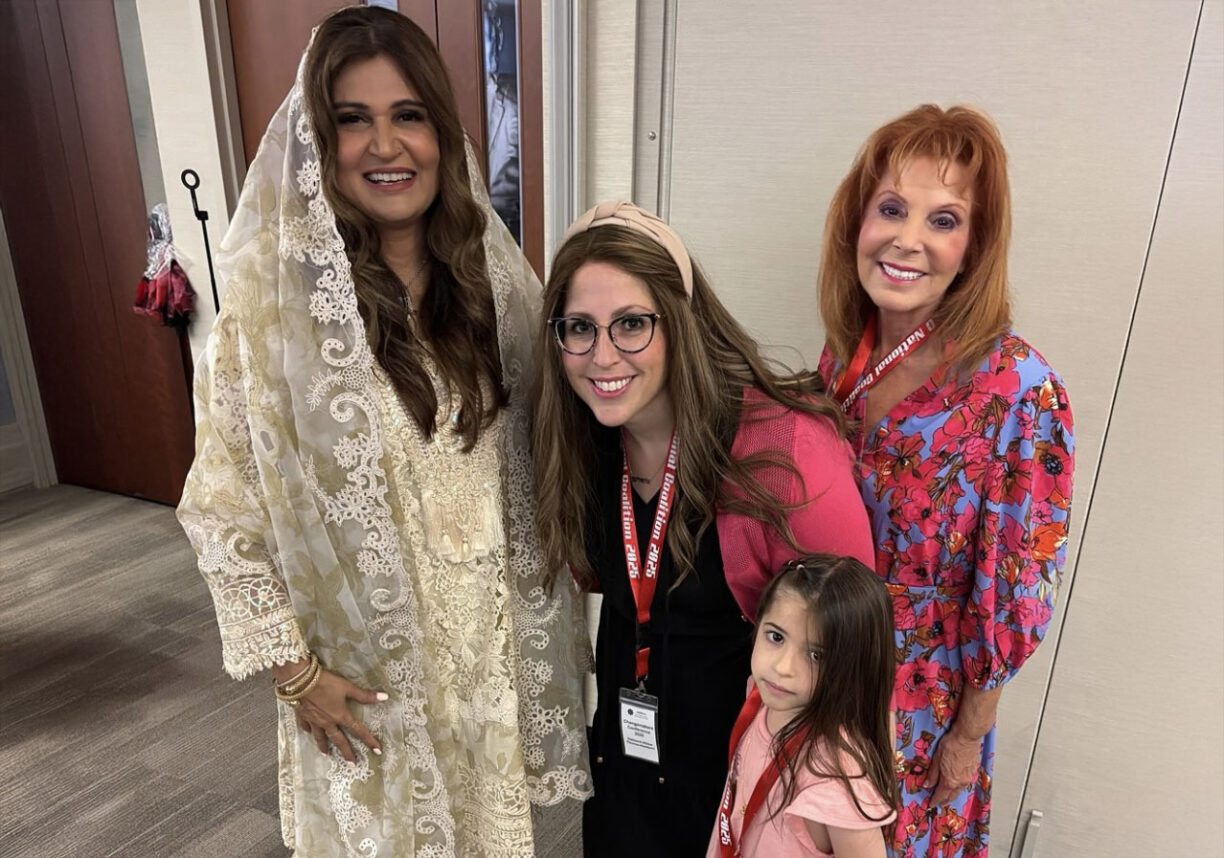

Now, years later, having grown up immersed in Judaism, studying at a Jewish school, learning to speak Hebrew, reading the Torah and honoring Jewish traditions, Dereve and Deboch are still waiting to go to the Holy Land. On Aug. 14, the young men stood before dozens of teenagers and staff at Camp Ramah in Ojai to ask them to help put pressure on the Israeli government to allow them to fulfill their dream.

“We believe that our homeland is Israel,” Deboch, 24, said. “We believe we are brothers. We are from one ancestor — we came from Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.”

“It is time to return to our country,” Dereve, 21, added. “We came here to make it soon, and to ask for help from you.”

Dereve and Deboch’s stop at Camp Ramah, a Conservative Jewish summer camp located about 80 miles north of Los Angeles, was part of a monthlong speaking tour organized by a group of American Jewish leaders and rabbis sympathetic to the plight of some 9,000 Ethiopian Jews waiting for aliyah in transit camps in Gondar and the country’s capital, Addis Ababa. These Jews, known as the Falash Mura, a pejorative Ethiopian term that means “outsider,” profess to come from a long line of Jews, although some of their ancestors converted to Christianity in the 18th and 19th centuries, often because of persecution and economic duress.

Over the past 30 years, tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews have immigrated into Israel, including thousands of Falash Mura, with the help of the Israeli government. In 2013, the Jewish Agency announced the end of Ethhiopian aliyah, saying that Israel had finally “closed the circle” on returning these Jews to their ancestral homeland.

The 9,000 Falash Mura still living in Gondar and Addis Ababa, many of whom have relatives in Israel, did not qualify as Jewish under the country’s Law of Return. That law requires at least one Jewish grandparent and does not accept people who converted to another religion in the past. However, in November of last year, under mounting pressure, the Israeli government agreed to allow the remaining 9,000 Ethiopian Jews to immigrate.

That immigration has yet to happen. In February, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said the state didn’t have the $1 billion it needed to absorb the remaining Falash Mura into Israeli society. A later agreement to bring some of the Falash Mura to Israel starting in June has stalled.

The delay is “devastating” for the Falash Mura, said David Elcott, a professor at New York University’s Wagner School of Public Service, who helped organize Dereve and Deboch’s visit to the United States.

“These guys both have siblings in Israel, aunts and uncles in Israel, cousins in Israel, nephews and nieces in Israel that they have not seen in 15 years,” Elcott said. “The idea that we would consciously and knowingly tear families apart is unconscionable just on a humanitarian basis.”

So far, Devere and Deboch have visited Jewish leaders, summer camps, rabbis and other members of the Jewish community in New York, Florida, Washington, D.C., and now Southern California. They spent three days at Camp Ramah, where they shared meals and participated in services, as well as speaking directly to about 500 campers.

They are asking American Jews to put pressure on the Israeli government to speed up the immigration of the Falash Mura by signing an online petition. More than 600 people have signed the petition, accessible through the Facebook page titled “Return to Zion — Completing the Exodus of the Ethiopian Jews.”

Dereve told the Journal he has enjoyed meeting American Jews and is happy to be able to share his people’s story. But he also feels angry that he has to go to such lengths to achieve what he considers a birthright.

“We think and hope that the situation now will change and we will do aliyah and move to Israel,” he said, speaking in Hebrew through a translator. “But I think to myself, why are we asking for help all the time? Why can’t we just be like any other Jews? … We have to come all the way to America and talk about it and ask for help.”

The two men told the Journal their lives in Ethiopia are forever on hold as they wait to go to Israel. They said their community also is terrified by current ethnic strife in Ethiopia, and they worry that Jews — already ostracized by Christians and Muslims — will become targets.

Both men said when they move to Israel, they intend to join the Israeli army. Deboch, currently a university student in Ethiopia, dreams of becoming an ambassador. Devere’s goal is to be a doctor.

Rabbi Joe Menashe, Camp Ramah’s executive director, said his decision to have the Ethiopians visit the summer camp was not an official endorsement of their request for support. However, Menashe said he believed campers would learn from the speakers about the broader Jewish community and the role of the State of Israel.

“At Camp Ramah, we believe in the State of Israel, we believe in the Jewish people, we believe in Jewish values, and this is something that touches all of those, and expands and exposes our kids to a real living, breathing part of the Jewish people,” he said. “We’re not just teaching about a subject in school, but we’re teaching about something that shapes who we are and the trajectory of lives.”

Some of the campers said they had already heard about the plight of the Ethiopian Jews, while others said it was their first time. Many marveled that the men had come from such a faraway place to visit.

Camper Aliza Abusch-Magder, 15, of Atlanta, said she was deeply touched by the men’s story and felt heartbroken that they have not been able to go to Israel.

“I thought it was really incredible. I mean, Israel is somewhere that was created as a safe haven for Jews and yet the Jews who need the safety and the love of the community the most aren’t getting it,” she said. It’s “really upsetting because it’s not how I like to picture Israel.”

Bradley Gerber, 15, of West Hills, said he was impressed with Dereve and Deboch and intended to sign their petition.

“I think it’s incredible that people from halfway across the world have such a passion to go to Israel,” he said. “I wish them the best of luck.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.