Ed Elhaderi (middle) with high school classmates in Libya in 1967. Photos courtesy of Ed Elhaderi

Ed Elhaderi (middle) with high school classmates in Libya in 1967. Photos courtesy of Ed Elhaderi A Libyan’s nomadic journey of self-discovery and understanding

That hot afternoon seems like yesterday, but it was 50 years ago this month. I was 15 and living in Sabha, a small city in the Sahara Desert of southern Libya. An older cousin told me about the reports on Cairo Radio about the dire situation facing the Egyptian army.

“We’ve got to do something,” he said.

I didn’t fully understand the politics of what would come to be known as the Six-Day War, but I knew that what was happening was bad for us as Arabs and Muslims. All around me were other teenagers absorbing the tense mood and looking to vent their rage at the Jews.

I followed the crowd to the only Western-style establishment nearby, a bar. It was early afternoon and the place hadn’t opened yet. A few older boys broke down the door, and a crowd stormed in, breaking bottles and dumping alcohol onto the street outside.

Standing in a crowd, I joined the chants: “Death to the Jews!” “Drive the Jews into the sea!”

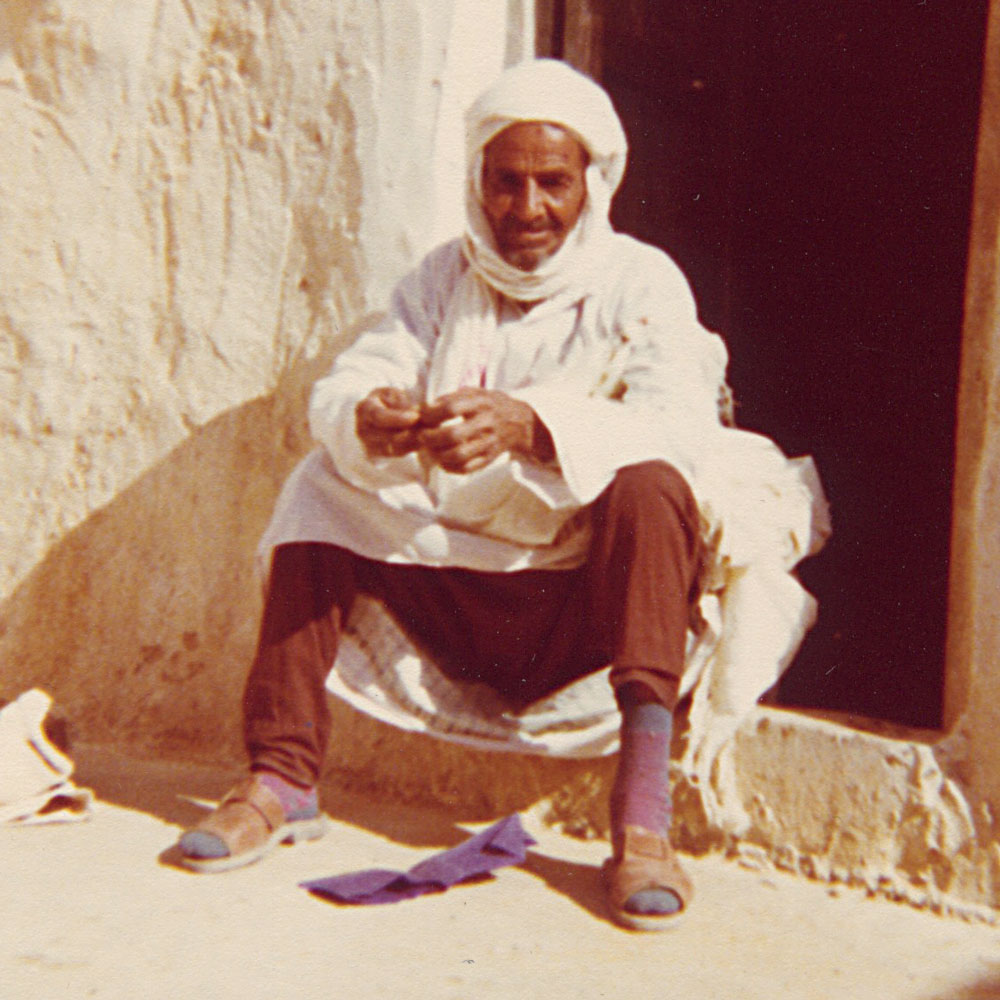

The truth is that I had never actually met a Jew. I grew up in a small nomadic village of 20 families, a collection of mud huts with palm-frond roofs that wouldn’t have looked much different 2,000 years earlier. Health care was so primitive that by the time I was a young boy, my parents had lost three children to illness.

Sunni Islam was the only way of life I knew. My preschool was in a mosque, where an imam taught us to read and write by drilling us with verses from the Quran. After that, our education was more secular — I went to mosque, going through the motions, but I was hardly devout. I never was exposed to any alternatives or avenues to question the life we had.

Our textbooks didn’t mention Israel, and people used the word Yahudi, Jew, only as an insult. The Jews had rejected the Prophet Muhammad, so they were considered to be condemned. The only Jews I saw were in Egyptian movies, in which they were portrayed as menacing, monstrous characters — hunched over and speaking with high-pitched nasal accents.

I did know Palestinian Arabs. My elementary school had once hired a young Palestinian as a teacher. Because he was Palestinian, the community welcomed him warmly and supported him generously.

After high school, I went to the University of Tripoli, where I was neither politically active nor religiously observant. During my first year there, my father arrived to deliver tragic news: My mother had died. I channeled my grief into focusing on my studies, earning a place in the prestigious chemical engineering program.

Hoping for a career in the country’s burgeoning oil industry, I won a scholarship to study abroad in one of the top-ranked programs in my field, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Leaving behind my father and one younger brother, I set out for my first journey beyond Libya.

In Madison, I discovered a campus teeming with international students — Iranians, Nigerians, Europeans, Asians. Amid the activist ferment of the mid-1970s, each group freely and openly expressed its political and cultural identity.

I did that, too: When I moved into an office I shared with two other graduate students, I tacked up a large poster of Yasser Arafat, the Palestine Liberation Organization leader, wearing his iconic kaffiyeh and brandishing a semiautomatic rifle.

It was 1974, just two years after the murder of Israeli athletes and coaches at the Munich Olympic Games and the same year as the terrorist massacre in the Israeli town of Ma’alot. Half of the department’s faculty and perhaps a quarter of its students were Jewish, yet it didn’t strike me that my choice of décor might offend anyone. Many colleagues undoubtedly reacted by steering clear of me.

And then, for the first time, I began getting to know Jewish people. The encounters happened organically, in classrooms and the student union. Two Jewish professors in my department were kind and understanding. Over one leisurely summer, I spent time with a Jewish philosophy professor who engaged a group of us over beers in leisurely discussions about politics and life. I was struck by how they were just people — wonderful, decent, normal people. They defied every stereotype I had been fed while growing up in Libya.

The contrast was so striking that not only did I begin to reconsider my assumptions about Jews, but I also came to re-examine every aspect of my life. Gradually, I came to see how the black-and-white worldview I had grown up with didn’t jibe with reality.

The more experiences I had with Jews, the more I felt drawn to them. I even began thinking that I wanted to marry a Jewish person (although I didn’t have a particular one in mind). Perhaps that would help me to cleanse myself of the hateful mindset of my upbringing.

After three years in Madison, I transferred to USC. A few months after arriving in Los Angeles, I was practicing tennis at the Ambassador Hotel when I struck up a conversation with an attractive young woman named Barbara and suggested we volley. When I told her my background, she said, unprompted, “I just want you to know, I’m Jewish.”

We exchanged phone numbers, and a week later, I called her. It took a couple of weeks before we connected again, meeting to play tennis and dine on Mexican food. We got along well. Not long after that, I went out of town to take a break from my studies and returned to find a note from Barbara telling me she missed me.

Before long, she invited me to meet her parents. Barbara’s father had lived in Israel, serving as an officer in its War of Independence. And one of her sisters’ boyfriends was an Israeli who had served in the Israel Defense Forces.

I’m sure that when they learned that she was dating a Libyan named Abdulhafied (the name I had grown up with and still used), they thought Barbara had lost her mind.

Still, we grew closer. After a couple of months, we moved together into an apartment her parents owned in Koreatown. At first, the arrangement was one of convenience, but soon our lives became intertwined. Barbara lovingly helped me through my doctoral thesis and cared for me in ways no one had since my childhood.

She also welcomed me into her family’s life, and, despite our contrasting backgrounds, her parents accepted me with love. Barbara’s family wasn’t particularly observant — they celebrated only Rosh Hashanah, Chanukah and Passover.

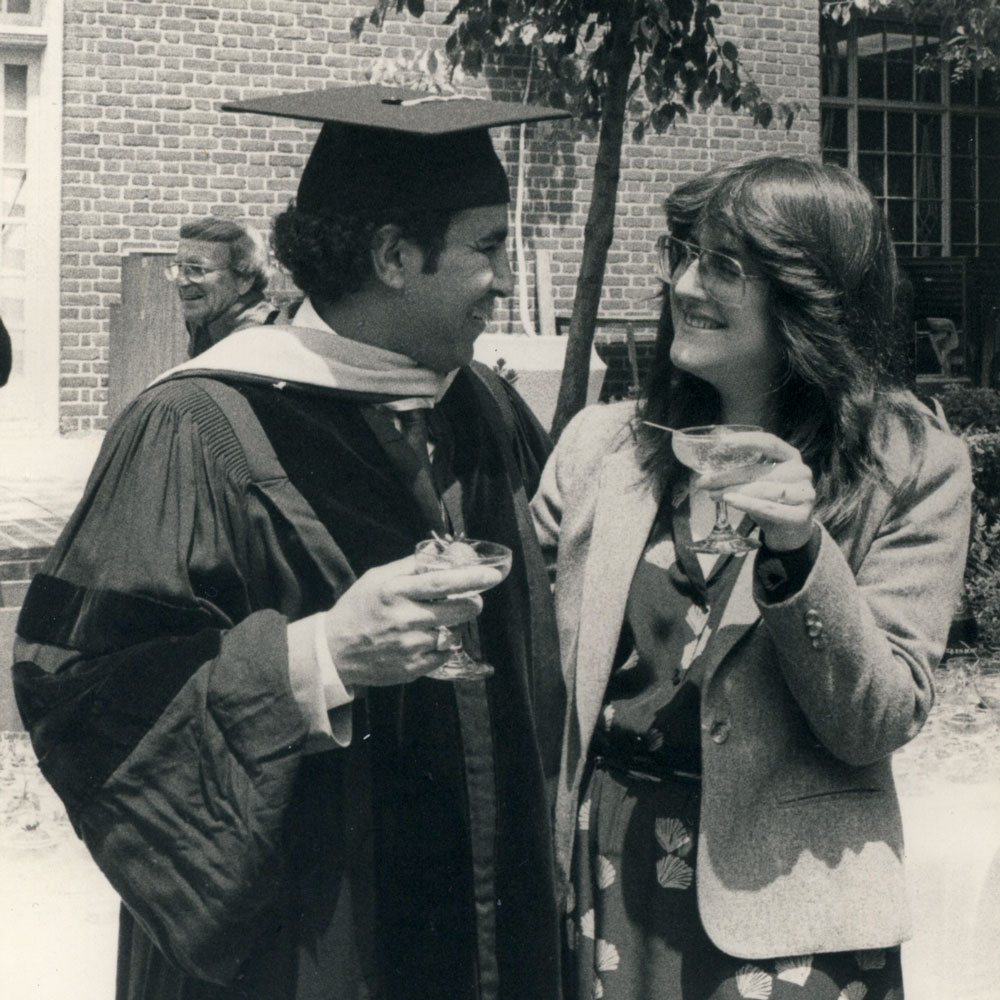

In 1980, we married at their Fairfax District home. At that point, I didn’t consider myself a Muslim, but rather a spiritual searcher. Together, Barbara and I had explored a nondenominational church called Science of Mind. Our wedding ceremony blended elements of Judaism with some of our own personal touches.

By then, my relationship with my aging father, still back in Libya, was distant. I spoke to him only occasionally, and his question was always: “When are you coming back?” I chose not to share the news of my marriage.

As we settled into our life together, Barbara and I had only limited Jewish observances: Rosh Hashanah dinners, Chanukah gift exchanges, seders hosted by her parents. Together, we continued our spiritual search, occasionally joining a colleague of Barbara’s at Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church in Lake Forest.

Eager to start a family, we struggled with infertility for many years. We were just days from adopting a baby when the birth mother had a last-minute change of heart. Then, just a week later, Barbara learned she was pregnant. Our daughter, Jessica, was born in 1991 and, two years later, we had a son, Jason.

Not long after that, my father died. We had spoken only occasionally since my last visit to Libya, in 1979. I had shared little about my new life with him, knowing it would have been nearly impossible for him to grasp the pluralism and openness I had come to cherish.

Surely he couldn’t have imagined the next step in my spiritual journey. When Jason turned 12, he announced that he wanted to have a bar mitzvah. We were living in the Pico-Robertson neighborhood and a neighbor, the Israeli-born wife of a rabbi, offered to teach him to read Hebrew and start some initial religious study.

He also began studying Judaism and his Torah portion with a Chabad rabbi at a shul not far from Barbara’s parents. I sat in on every class, slowly learning about Jewish prayer and customs, as Jason studied his haftarah and maftir. The more I absorbed, the more I felt drawn to Judaism.

On the day he became bar mitzvah, I stood on the bimah, filled with pride in my son and awe for the beauty of the service I could barely understand — and overflowing with emotions I could not fully explain.

The power of that day also made me start to ponder my own mortality. It pained me to realize that since I wasn’t Jewish, I could not be buried in a Jewish cemetery beside my beloved wife.

Not long after the bar mitzvah, I told Barbara that I wanted to convert to Judaism. A rabbi we knew directed us to American Jewish University’s Introduction to Judaism Program, and Barbara and I enrolled.

Our 18 months in the class felt like a second honeymoon: While I learned about Jewish history, Torah and Jewish rituals, I felt closer than ever to Barbara, and I fell in love with Judaism.

When I met with my sponsoring rabbi, Perry Netter, then at Temple Beth Am, he asked only one question: “Why do you want to be Jewish?” Choked up with emotion, I couldn’t speak. I simply cried.

“OK,” he said, smiling. “You pass.”

Something else happened: The more I learned about Judaism, the more I saw parallels in my own upbringing in Libya. When I learned about the mezuzah, I remembered how in my childhood village, families posted palm fronds wrapped around verses from the Quran in their doorways. Words I learned from biblical Hebrew seemed to echo colloquial terms unique to the region of my youth.

Investigating, I learned that Jews had lived for thousands of years in Libya, including in my native region of Fezzan — although most left in 1948, and nearly all of those remaining fled just after the Six-Day War. My strong feeling was that I wasn’t so much discovering a new faith as uncovering a long-hidden part of myself, that perhaps some of my ancestors were Jews.

On the morning when I went before the beit din — the rabbinical court — to finalize my conversion, and plunged into the waters of the mikveh, I felt joy combined with a serenity that had eluded me for decades. I felt that I was returning to where I belonged.

Our family joined Temple Beth Am, where I felt increasingly at home, regularly attending on Shabbat and weekdays. At home, we shared weekly Shabbat dinners, at which I started offering each of my children a blessing.

I also engaged in regular Torah study and found particular resonance in Rabbi Akiva’s wisdom from Pirkei Avot: “Everything is foreseen, yet free choice is given.”

That essential tenet — that we can embrace God but decide our own fates — encapsulates much of what I hold dear about America and Judaism. I grew up like so many people in closed societies, knowing one way of life, having one set of beliefs, and taught to despise anything beyond that realm.

The best guidance for overcoming that kind of internal and external strife is another piece of advice from Pirkei Avot: “Who is wise? The one who learns from all people.”

My own learning came full circle in November 2012, when Barbara and I traveled to Israel. We landed in the late afternoon, and by the time we arrived at our Tel Aviv hotel, Barbara wanted to rest, but I felt energized, so I took a walk. Traversing the streets of Tel Aviv and Jaffa until midnight, I marveled at the variety of people I saw — young and old, from so many ethnic backgrounds. I was amazed by the sights and smells and how alive the city was.

Scanning the faces I passed on the street, I could not help but think back to my youth, to the hatred for Israel and Jews that had been fed to me. As we traveled the country — Jerusalem, Safed, the Golan, Rehovot — Israel entered my bloodstream. I felt at home.

The trip deepened my connection to Israel and to being Jewish. In synagogue on Shabbat mornings, I began to take notice of a part of the service that I hadn’t thought much about: the prayer for the State of Israel.

Now I say it each week with full intention: “Bless the land with peace, and its inhabitants with lasting joy.”

Occasionally, as I say those words, I think back to my 15-year-old self, on that hot June afternoon on the streets of Sabha. And I say an extra prayer of gratitude to God for carrying me on this remarkable journey to myself.

ED ELHADERI is a real estate investor and developer who lives in West Los Angeles with his wife, daughter and son. He is writing a memoir about his journey from his Libyan childhood to his life as an active and committed American Jew. Tom Fields-Meyer is a Los Angeles author and editor who helps people tell their life stories in writing.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.