Most vivid memories are not

of victories, but crisis and defeat.

It’s harder to remember what

caused you to feel elated and upbeat

than to recall the moments when

you felt your life had spun out of control,

preventing you to reach again

the top of life’s egregious, greasy pole.

The Bible helps this process, ending

with Emperor Cyrus’ famous declaration,

defeat of the Judeans mending

with restoration of our Jewish nation.

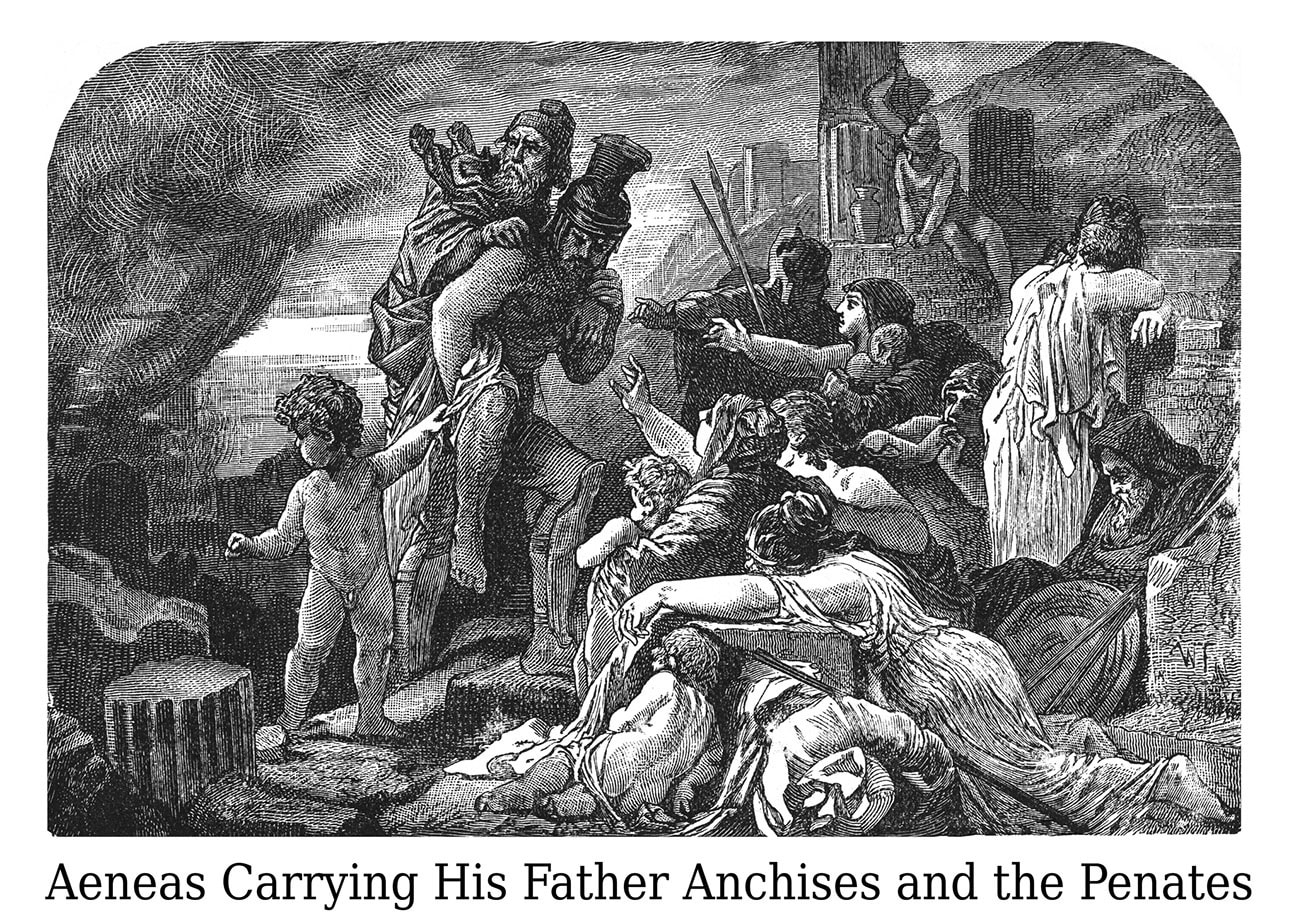

The Aeneid does this in a dream

in which Aeneas was the mythic founder

of that great city which would seem

to be than Troy romanticized far sounder.

Fortune reversal is the trope

the Bible and the epic Aeneid share,

a Rome before there was a pope

where pius prince Aeneas had to dare

to travel to, while we, in Persia,

refuseniks, to Jerusalem were told

to go, although due to inertia,

what later was in song compared to gold

was not rebuilt in Cyrus’ era….

like ancient Rome not built in just one day,

though every day brings all Jews nearer

to what all pious Jews thrice daily pray.

In “How the Authors of the Bible Spun Triumph from Defeat: History may be written by the victors, but the world’s most influential text comes from antiquity’s biggest losers,” The New Yorker, 8/21/23. Adam Gopnik, reviewing Why the Bible Began by Jacob L. Wright, writes:

The pagans who dominated the world lost their gods when they lost their empires and saw them swept into myth by the monotheistic religions spawned from the Jewish one. And the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament, is, perhaps, unique on the planet inasmuch as it is, as the scholar Jacob L. Wright suggests in his new book, “Why the Bible Began” (Cambridge), so entirely a losers’ tale. The Jews were the great sufferers of the ancient world—persecuted, exiled, catastrophically defeated—and yet the tale of their special selection, and of the demiurge who, from an unbeliever’s point of view, reneged on every promise and failed them at every turn, is the most admired, influential, and permanent of all written texts. Wright’s purpose is to explain, in a new way, how and why this happened.

The easiest explanation is that it happened this way because that’s the way God wanted it to happen. But this does not lessen the need to say how it happened. Or, as Edward Gibbon wrote, in one of the most perfect of sentences, explaining his ambition to provide a rational account for the rise of Christianity, “As truth and reason seldom find so favourable a reception in the world, and as the wisdom of Providence frequently condescends to use the passions of the human heart, and the general circumstances of mankind, as instruments to execute its purpose, we may still be permitted, though with becoming submission, to ask, not indeed what were the first, but what were the secondary causes?”….

Division and defeat, Wright explains, made the Bible memorable. Successive expulsions and exiles forced the Jewish poets and prophets, like Red Sox fans of yore, to imagine defeat as a virtue, dispossession as a gift, failure today as a promise of victory tomorrow. Defeat usually compelled other ancient peoples, as it does us, to invent rationalizations for what happened. (Yes, we failed to pacify Afghanistan, but nobody could have done so.) In the face of regular defeat, however, the Jewish scribes had to ask whether defeat wasn’t God’s will in the first place, and so opened mankind unto a new contemplative possibility: that spiritual success and failure were not to be judged on worldly terms. Nice guys, or, anyway, pious guys, finish last and should be proud of their position.

It occurred to me, after reading Gopnik’s review of Jacob Wright’s book, that the way the Bible celebrates defeat of the Israelites, by concluding the Tanakh with Cyrus’s declaration, inviting the Judean to return to Jerusalem and there rebuild the temple, echoes how the Aeneid celebrates defeat of the Trojans by recording the prediction of Anchises, Dido’s father, that Romulus would found Rome, providing a rationale for Aeneas’ escape from Troy and his journey towards what would become Rome.

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.