Rosh Hashanah is not an easy holiday to celebrate. It is supposed to be the beginning of a new year — 5778, according to the Jewish calendar — but most Jews live by the Gregorian Calendar. It is a holiday of reflection, but Yom Kippur is the more powerful symbol of soul searching and introspection. Passover is more fitting for a large family gathering. Purim is more cheerful. Hanukkah is more publicly extravagant.

Rosh Hashanah is the day of the Shofar, but many Jews associate the Shofar with the end of Yom Kippur more than with Rosh Hashanah. It is the day of apple and honey. But really, how excited can such symbols, such treats, make you?

And it is long. Two days in a regular year. This year it is three, if you add the following Shabbat. Three days of what? Family? Children running around looking for things to do? Synagogue? Making one day a special day is difficult enough; a three-day holiday is a headache.

The Mishna counts four Rosh Hashanahs. Tu Bishvat begins the year for trees. Nisan, the month of Passover, begins the year of Jewish Kings. In Elul we find the more obscure beginning of the year for the tithing of cattle.

Our Rosh Hashanah is the beginning of the year for many things that we no longer worry about. For example: the new year for setting the Jubilee year, the new year for non-Jewish Kings, the new year for calculating the 10 percent tithe on produce.

None of this remains relevant to Rosh Hashanah, known as the holiday of ending and beginning. It no longer ends or begins a fiscal year, or a year of kingly reign. It no longer feels, naturally, instinctively, as a calendar turning point. School doesn’t begin; summer doesn’t end. Nothing happens in the real world. To make it a turning point we need to work — psychologically, spiritually — to make it so. The beginning of a culturally-manufactured mental year.

We do that with prayer. We do it with ceremony. We do it by collectively agreeing to consider this completely ordinary time as a special time. “We,” that is the Jews. So Rosh Hashanah is not just a personal mental new year, it is also a mental new year of a collective.

A collective can do useful things with a mental new year. It can decide that this is the time for reflection, not on world events or on financial achievements and failures, but on the state of the Jews. The think tank I work for, The Jewish People Policy Institute, marks a new year by the publication of its annual assessment on the state of the Jews. That is a good way to make it a collective new year.

What happened to the Jewish people this past year? Did they manage — did we manage — to make ourselves better, to better position ourselves for dealing with the challenges ahead?

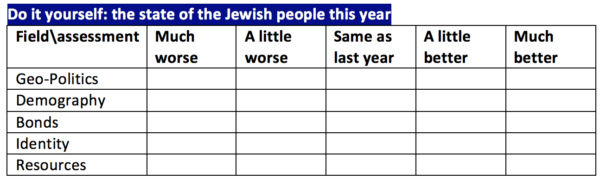

JPPI’s annual assessment includes five “gauges” for trying to measure something that’s very tricky to measure accurately and convincingly: the state of the Jewish people. We look at geopolitics. We look at bonds between Jews. We look at identification and identity of Jews. We look at demographics and at material sources.

The gauges give a snapshot of advancement and deterioration. But in all fields, there are complications.

Demographics hardly change every year unless there is a catastrophe. There was none this past year. Identity is often connected to ideology: Tell me what a Jew needs to be — a conceptual preference — and I will tell you whether the Jews progressed or weakened.

Like questions of personal introspection — such as, are you happier with more financial success or with more peace of mind — questions determining one’s collective introspection depend on priorities. Some Jews see a collective advancement if more intermarried couples are married by rabbis. Some Jews see a collective decline if more intermarried couples are married by rabbis. That is to say: the collective reflection is still very much personal.

Try it. Try to assess the state of the Jewish people this year before you go and read how JPPI assessed it. And here is a tool to help you: JPPI’s earlier assessments, for 2014-2015 (in blue) and for 2015-2016 (in green). The letters mean: Thriving, Prospering, Maintaining, Troubled, Decline.

So, for example, last year JPPI assessed that the geopolitical situation improved from the Jewish world’s perspective (you can see the analysis here), and that the bonds between Jews remained unchanged. Because any assessment must begin with a baseline, these last two years can serve as your baseline as you answer the questions that follow the graph:

Last year’s assessment by JPPI

Now, let’s turn to this year:

Are the geopolitical circumstances better for the Jewish people today than they were a year and two years ago?

Are bonds between Jewish communities, and especially between Israel and Diaspora communities, stronger this year?

Do we have more or fewer resources than we used to have in previous years

Do you see a change for better or worse in the way Jews form their Jewish identity?

Did you see an improvement in the demographic circumstances of the Jewish people?

JPPI’s assessments for this Rosh Hashanah are here: geopolitics, bonds, identity, demography, resources. Are urge you to take a look at them.

And no matter how you assess the state of the Jewish people, the fact that we are assessing it as a group, as a tribe of interested participants, shows that Rosh Hashanah still has an important and relevant role in the 21st century.

Shanah Tovah.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.