Adolf Eichmann was the first person to be tried in the State of Israel for Nazi war crimes. John Demjanjuk was the second and almost surely the last. Eichmann, of course, was found guilty in 1962 and hanged. Demjanjuk was convicted in 1988 and sentenced to the gallows, but his conviction was reversed by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1993 and he was sent back to the United States.

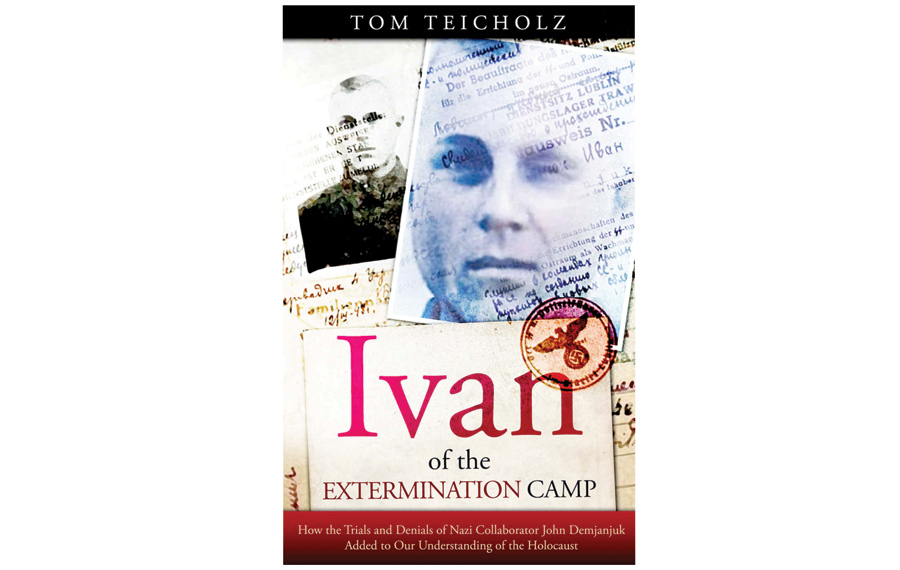

The strange and unsettling saga of John Demjanjuk has now reclaimed our attention because of two media events — the release of a Netflix documentary, “The Devil Next Door,” and the publication of “Ivan of the Extermination Camp: How the Trials and Denials of Nazi Collaborator John Demjanjuk Added to Our Understanding of the Holocaust” (Pondwood Press/Amazon) by Tom Teicholz, who features prominently as an on-camera expert and commentator in the Netflix documentary.

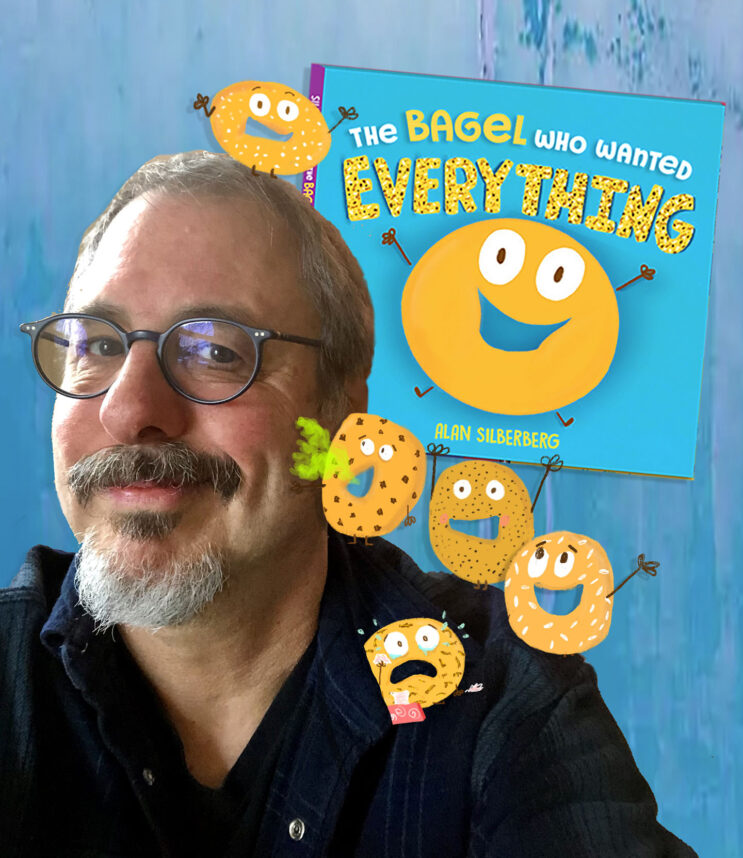

Teicholz is an award-winning author and journalist whose work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times and the Jewish Journal, among many other publications. Last August, I reviewed “9/12: The Epic Battle of Ground Zero Responders,” co-written by Teicholz and William Groner.

Teicholz covered the 1988 trial of Demjanjuk, and his account was published in 1990 as “The Trial of Ivan the Terrible.” Thanks to his expertise, as well as his remarkable gift as a storyteller, the producers of “The Devil Next Door” called on Teicholz to explain to viewers the exploits of Demjanjuk himself and the harrowing melodrama that constituted his prosecution in America, Israel and Germany. (Teicholz is, by the way, far and away the most astute and lucid of all the voices we hear in the documentary.) In “Ivan of the Extermination Camp,” Teicholz has returned to the Demjanjuk case, expanded and updated his research, and allowed us to glimpse yet another new and horrifying aspect of the Holocaust.

At the core of the story that is told in Teicholz’s latest book — which can be likened to a police procedural, an international thriller and a groundbreaking contribution to the scholarship of the Holocaust — is the deceptively simple question of whether a retired Cleveland autoworker named John Demjanjuk was or was not the Nazi executioner known by camp inmates at Treblinka as “Ivan the Terrible.”

Among the vast roster of torturers and murderers who were responsible for carrying out the Holocaust, the man called Ivan the Terrible distinguished himself by his sheer brutality and cruelty. Stationed at Treblinka, he used a weapon — “variously described as a knife, a sword or a bayonet,” as Teicholz reports — to prod his victims into the gas chamber, and when the spirit moved him, he would use it to slice off an ear or a breast. The moment before they were to be murdered, Ivan made sure they would suffer yet one more blow.

In “Ivan of the Extermination Camp,” Tom Teicholz has returned to the Demjanjuk case, expanded and updated his research, and allowed us to glimpse yet another new and horrifying aspect of the Holocaust.

Ivan the Terrible was a so-called “Trawniki man,” a term that was used to describe Ukrainian prisoners of war who were recruited by the Germans, trained at an SS camp called Trawniki and put to work in the concentration camps and death camps. So was Demjanjuk. Indeed, Teicholz calls Demjanjuk’s SS-issued identity card from Trawniki as “the Rosetta Stone, as concerned Demjanjuk’s history and what was to be gleaned from his Nazi service.”

Teicholz’s book deserves our praise for many reasons, but above all because he has added to our understanding of how Nazi Germany managed to kill Jews in the millions while, at the same time, fighting a two-front war. The more notorious Nazis, including Eichmann, never bloodied their own hands. But it was the Trawniki men, among others, who served as “the enthusiastic foot-soldiers in the murderous program to exterminate the Jewish race,” as Teicholz puts it.

Nowadays, we are confronted with the expertise of Russian intelligence agencies in campaigns of disinformation. Demjanjuk’s attorneys, too, argued during his trial that his Trawniki identity card was a KGB forgery. Then, too, Teicholz’s book comes at an especially fraught moment in the history of Ukraine, which is now consistently characterized as a heroic ally of the United States, and perhaps deservedly so. But “Ivan of the Extermination Camp” serves to remind us that the Ukraine, as it was known during the Soviet era, was also one of the killing grounds where Jews died during the Holocaust and a contributor of manpower for those who killed them.

After Demjanjuk’s conviction in Israel was reversed, he was deported from America a second time and later faced trial in Germany, where he was convicted of war crimes in 2011. He may not have been Ivan the Terrible, but the German court held him criminally liable for the deaths of 29,000 victims at Sobibor. But there was yet another appeal, and he died in bed at the age of 91 in 2012 while the appeal was still pending.

“In the end, after almost forty years of investigations and trials, Demjanjuk’s lies and evasions were reason for dedicated prosecutors, judges, researchers, historians, and experts of many kinds, in the United States, Israel, Germany, and even the former Soviet Union and Russia, to uncover vast new troves of information about the murderous actions of the Nazis and those in their service, such as Demjanjuk,” Teicholz concludes. “Regardless of politics, regardless of the government in power, regardless of the passage of time, these countries each showed themselves to be a nation of law.”

Whether or not John Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible himself, or just one of the many other Ukrainian collaborators who served Nazi Germany, does not ultimately matter. He was one of Hitler’s willing executioners, to borrow a phrase from the title of Daniel Goldhagen’s famous book, and yet, as Teicholz shows us in fascinating detail, Demjanjuk may have escaped the gallows but he did not escape justice.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.”