Like many readers, I first encountered David Rosenberg in “The Book of J,” a provocative study of the passages in the Hebrew Bible that are attributed by biblical scholars to the source known as “J.” His co-author, Harold Bloom, famously argued that J might have been a woman; Rosenberg contributed a fresh and felicitous translation of the Hebrew words and phrases that she contributed to the Bible. Since then, I have come to know and admire Rosenberg’s body of work as an editor, poet, translator and biographer, including “A Poet’s Bible,” “Abraham: The First Historical Biography” and “An Educated Man: A Dual Biography of Moses and Jesus.”

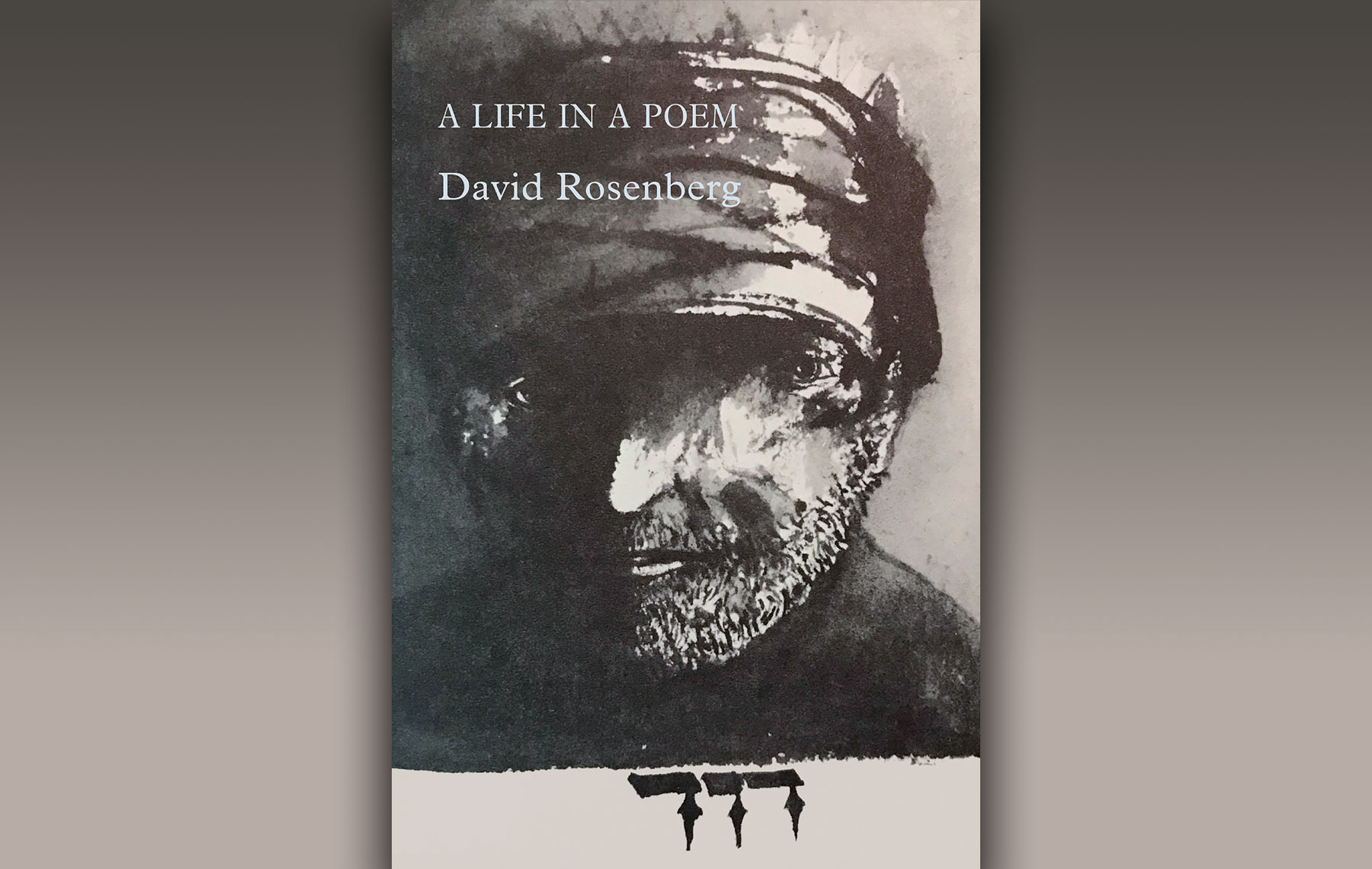

Now Rosenberg looks back on his own rich and accomplished life in “A Life in a Poem” (Shearsman Books). To call his book an autobiography, however, understates the scope and depth of what he has accomplished using the raw material of words on the printed page. While it is certainly a “dossier of self-interrogation,” to borrow one of the author’s intriguing phrases, “A Life in a Poem” also is a tapestry whose vivid strands are drawn from both high culture and popular culture, both the intimate personal experience of the author himself and the tumult of history.

“If you asked me what I wanted to be at age 6, it was the back alley scrap man (he had a horse and interesting junk); at 14, it was Tony Curtis (I was an understudy at Detroit’s Vanguard Theatre),” Rosenberg muses. When it came to soul, he assumed that it was “merely what my Brady grade-school classmate, Aretha Franklin, would soon be associated with.” The notion that soul was deeply rooted in religion did not occur to Rosenberg “until I began translating psalms in the early ’70s.”

“A Life in a Poem” is a tapestry whose vivid strands are drawn from both high culture and popular culture, both the intimate personal experience of the author himself and the tumult of history.

Indeed, it is the Bible that remains the touchstone of Rosenberg’s life and work, and much of the poetry in “A Life in a Poem” is inspired by or, often, extracted from the Bible. He wants us to approach the Bible as a work of human authorship: “What you get is human history condensed into the drama of Israel,” he muses. “What you won’t get are answers to your anxieties about belief, faith, and the afterlife — those questions must be left at the door.”

Rosenberg reduces (or elevates) the whole of the Bible into the realm of poetry: “It’s my contention that, more than a story or history, your reading of the Bible requires you to accept it as a poem,” he writes. And Rosenberg says the same of his own life story: “Anyone’s life is a story but life itself is a poem,” he proposes. “While I look at my personal history from a different angle in each chapter of this book, I always come back to the Bible and to a defense of poetry.”

Similarly, Rosenberg urges us to see and hear the flesh-and-blood human beings who were the authors of the Bible. “The latter prophets do not fail to make themselves characters in their authorship,” he writes. “I was quite aware of this when, not quite 13, I read from Isaiah for my bar mitzvah haftarah. I practiced the text for a year, spellbound by Isaiah’s crying, which I heard in the plaintive tone of the rabbi at my Zaydeh’s graveside when I was eight, singing ‘El malei rachamim’ to help the soul find its way to heaven.”

Rosenberg’s assumptions about the human authorship of biblical writing may be off-putting to some religious Bible readers, but he remains untroubled by the whole question. “Does one have to believe a Creator to hear Jonah’s song?” he asks, referring to his translation of the Book of Jonah (“Behind me / it was the end of the world for me — and yet”). “Billie Holiday in her stylings or the original Dada poets don’t stop making poetry; their work intuits creation and a belief in their existence.” Characteristically, he finds a commonality between the prophet and the blues singer: “So I would ask, Is there really much difference between belief in existence and belief in — or wish for — immortality, a soul that comes from and returns to nonexistence?”

“A Life in a Poem” also serves another function; it is nothing less than an index of Western civilization. Thus, for example, Rosenberg characterizes a 1990s science fiction film titled “Deep Impact” as both “an ordinary piece of pop culture” and “a major Montaignean radish,” which is only the starting point for a search for the meaning of life as it is lived in the apprehension of death (of the individual, the species, the planet or the cosmos), not only in the movie itself but also “Montaigne’s essays, Shakespeare’s plays, Freud’s theories, and the latest literary novel.”

Rosenberg is not a secularist; in fact, he embraces all artifacts of the human hand and the human mind as potential sources of spiritual meaning or, as he puts it, “the knowing that is numinous.” He compares the prehistoric cave drawings at Chauvet to the passages of Scripture that depict “Adam and Eve when they’re speaking with the Creator, or Abraham questioning God on the way to Sodom and Gomorrah, or Jesus addressing God the Father from the cross.” As “created beings,” we are impelled to imagine “the Creator,” he insists, and we are inspired to create “existential representations of something more than ourselves.” And he affirms: “That is what I mean by religion.”

As a young writer, I was both informed and inspired by the memoirs of Nikos Kazantzakis (“Report to Greco”) and Henry Miller (“The Colossus of Maroussi”) and, in a larger sense, the novels, essays and short stories that amount to an autobiography of Isaac Bashevis Singer. David Rosenberg’s “A Life in a Poem” belongs on the same shelf as these precious books, and that’s where I will put my copy of his latest work.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.