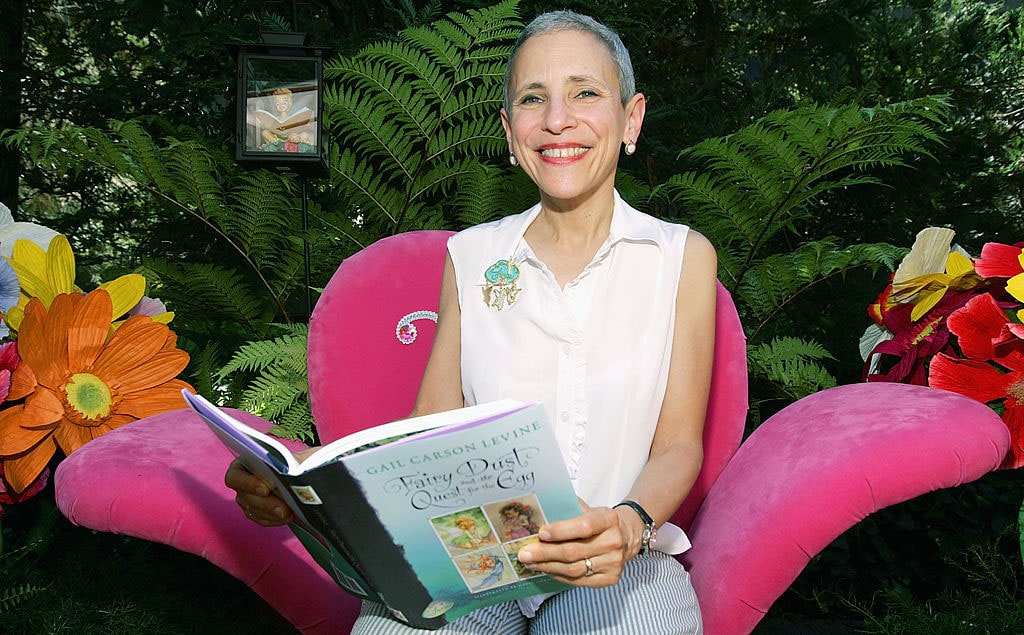

Bestselling author Gail Carson Levine didn’t always know that she wanted to be a writer. The daughter of a Turkish immigrant, Levine grew up in Washington Heights, befriending children of German Holocaust refugees. Levine spent over two decades working in social welfare before getting published.

Her father, David Carson (formerly David Carasso), never lived to see Levine’s success, though she remembers how he once called her “determined.” He was right. Levine’s writing received rejection after rejection, but she never gave up. Her perseverance paid off with the publication of “Ella Enchanted,” a unique retelling of Cinderella featuring a heroine cursed to obey any order. Levine’s captivating debut novel won the Newbery Medal in 1998.

Since then, Levine has written over two dozen novels. Her latest work, “A Ceiling Made of Eggshells” (HarperCollins, 2020), is a riveting and heartwarming tale about a young Jewish girl, Loma, accompanying her grandfather on an expedition to save their people during the Spanish expulsion.

JJ: You don’t see many middle-grade books about the expulsion of 1492. What motivated you to create a story in this time period?

GCL: It’s because it’s family history on my father’s side. He was Sephardic. I knew what had happened to Sephardic Jews, but it was nothing he ever talked about. I don’t know if it was anything he ever thought about. But his first language was Spanish — so, probably Ladino. He lost it because he came [to the United States] so early.

So, I wanted to explore [the expulsion], and I knew nothing when I started. I knew only that there had been an expulsion, and I knew the year. But I didn’t know anything about the times or what the reason was [for the expulsion], aside from getting rid of the Jews. It’s more complicated than that, and I learned a lot about what happened.

JJ: The attention to historical detail in “A Ceiling Made of Eggshells” is amazing. What was the most challenging part of the process?

GCL: The history itself was not as challenging because I discovered what happened, I created a timeline, and I hung my plot around that timeline once I decided where to start, because the beginnings of the end were a hundred years earlier — and even more as the tide turned against the Jews of Spain.

One of the challenges was understanding what I was reading. Loma’s grandfather is very loosely based on Isaac Abravanel, and he was a philosopher, but he was also a financier to the monarchs, to important people in the Church.

The kind of detail that you don’t find in the history books — what places smelled like, what a street looked like, what would the interior be like, what the furniture was — that required a lot of sleuthing.

One of the books that I read was “Expulsion” by Haim Beinart, and I read it twice. The first time I didn’t understand it all because what it is primarily is an accounting of court cases and fiscal, financial transactions (who bought what and when and what happened)… Creditors would immediately go after Jews to collect what was owed, and debtors to Jews would delay payment because they knew that the Jews would be gone. The tragedy [of the expulsion] is woven into those very dry financial transactions.

But it was such a discovery. I loved all the reading that I did. I had a mentor, Jane Gerber, who is a Professor Emerita at CUNY, City College of New York. She guided my reading, and some of it I found on my own. I read a biography of Isabella, which was not from a Jewish perspective, and that kind of widened it. I read a book about slavery. I read a book a little bit after the period about ships and sailing at the time because all of it I needed. It might be just a sentence [that I needed], and I would have to read fifty pages.

JJ: “A Ceiling Made of Eggshells” was loosely based on your family’s Spanish ancestry. Was it a very emotional journey for you?

GCL: Sure, it was. I didn’t know how much tragedy there was. I didn’t know that half the Jews converted. I didn’t know about anti-Semitic sea captains dumping their passengers overboard or depositing them on uninhabited islands or selling them to pirates. Earlier, when Jews found themselves enslaved, the Jewish community, wherever they wound up, would buy their freedom. But at the time of the expulsion, there was no Jewish community to [pay the] ransom.

So, yes, it was emotional because it was so terrible. And then there was emotion in [wondering] how did we make it? How am I alive? Who was brave enough, intelligent enough, clearheaded enough, fearless enough to get us out of there to safety? And that’s where Loma and the family that I made up — especially Loma — comes into it.

JJ: You’re a native New Yorker. Did you have a traditional Jewish childhood?

GCL: My parents were High Holy Day Jews, so we went to the synagogue. I don’t remember learning I was a Jew. I was always a Jew. So, I’m not observant, but I identify very deeply as a Jew.

JJ: How has your faith influenced your writing?

GCL: It’s brought me two-and-a-half books. “Lost Kingdom of Bamarre” deals pretty directly with prejudice. I was thinking about prejudice against Jews, and I was thinking about racial prejudice when I wrote it. I don’t think [anti-Semitism] ever held me back, but I have experienced it a few times. The assumptions that people who are prejudiced make about Jews are hurtful.

JJ: Many of your novels have been celebrated for their feminist themes. What inspires you to create such strong female protagonists?

GCL: I was very lucky. My father didn’t complete high school. My father was very smart, and the orphanage sent him to a special high school. Once he escaped the confines of the orphanage… he didn’t finish high school, which I think was a blight on his life.

My mother finished college at 16 and was the first [person], by marriage, in his family to finish college. And my father was exceedingly proud of her. He loved how brilliant she was. So, I never got any messaging from either of my parents that being smart was a problem for a woman. That was great, and passing that along, I think, is something worth doing. That may be a part of it.

If my main character is female, she has to have agency. She has to have the strength to control her own story. Otherwise, the fairy is swooping in saving her or the prince is. That’s another reason.

JJ: It has been over twenty years since the original publication of “Ella Enchanted.” It remains one of the most beloved fantasy books in classrooms across the country. Why do you think the story continues to be embraced by new generations?

GCL: Because everybody’s cursed with obedience. Nobody escapes that one — kids most of all. [“Ella”] strikes that chord, I think, for everybody. I didn’t know that I was doing that [when I wrote “Ella”]. I did it to explain to myself why Ella was so kind to [her] step-family and why she did whatever she was told. But people pointed it out to me, and it seems to be true.

I’m obedient. I do things that I don’t want to do for reasons that I think are reasonable because [I] weigh the consequences. So, that’s why I think it stays relevant. If we’re going to live in a civilization, I don’t think a day will ever come when people are not cursed with obedience. I don’t even know if it should.

JJ: What did you think of the [2004] film adaptation of “Ella” starring Anne Hathaway and Hugh Dancy?

GCL: Well, I think that Anne Hathaway was a great Ella and couldn’t be better. I was so thrilled when she was cast. I thought Hugh Dancy was good, too. He was Black in my book. If you look at his skin color, he’s dark. But they [the filmmakers] didn’t do that.

I think it’s a fun book, and I think you need to keep [the movie and book] separate. I’m glad [the movie] was made because it continues to bring kids to the book, and that’s what I care about. I always say this when I talk to kids — I say, “Do any of you want to be directors or producers?” A few raise their hands, and I say, “When you get there, remember I have many books.” Because I’d love to have it happen again. It was an adventure.

JJ: You’ve written two books about writing, “Writing Magic” and “Writer to Writer.” You continue to offer creative writing workshops over the summer. What makes you passionate about inspiring and guiding young writers?

GCL: I feel very lucky. I started doing this with the local middle school every week, which eventually got to be too much. But I’ve continued doing it every summer. I think almost all writers struggle with self-criticism. That can be very damaging. My high school English teacher told me that I was “pedestrian” — not just my writing, me. That kind of [criticism] is like an injection of negativity. I hope to inoculate people against that. I have to struggle to inoculate myself.

I’ve discovered that when I’m writing something, the least useful thing I can decide … is whether or not it’s good. [Authors] do have to be self-critical, to be alert to whether the pace is fast enough or too fast, if we’re rushing things, if our characters are behaving the way we’ve set them up, if readers will get lost — lots of things that we have to think of that are very specific, but not whether what we’re writing is boring or good or clichéd. All of that makes it harder to write. That’s one of the reasons I wrote “Writing Magic” and “Writer to Writer.”

I continue to write my blog, and I continue to teach. I love teaching the kids. It’s really a treat.

JJ: What can you tell us about your upcoming book about the Trojan War?

GCL: As a kid, I loved reading about Greek mythology. Edith Hamilton’s [“Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes”] pages are falling out. I read it and read it and read it. Then, when I started thinking about it… I turn[ed] it into an adventure rather than a tragedy. I’m sure Homer is spinning in his grave. It is my homage to Greek mythology, which I love so much.

The interview has been edited for brevity.

Eve Rotman is a writer on the West Coast.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.