After seeing two newly-released films, I was not surprised that one of them caused deep reflections about the tragedy of the Holocaust. What surprised me is which one.

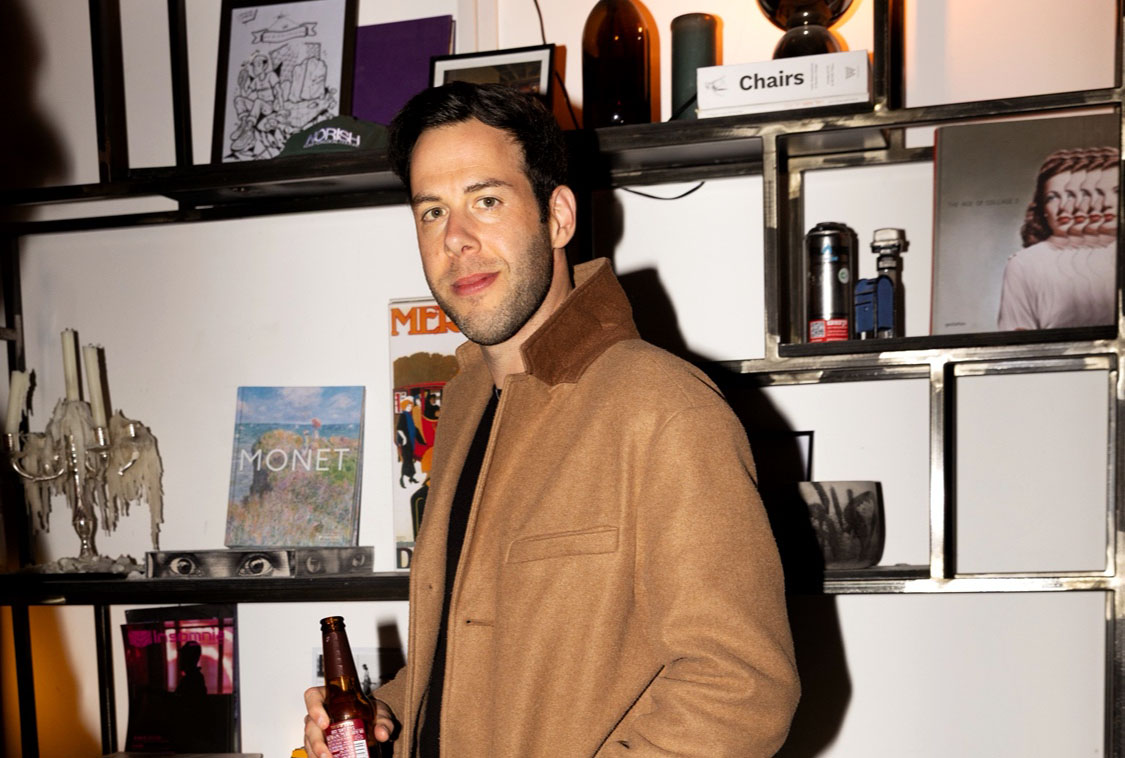

The first of the two movies was “Nuremberg,” an unusual take on an excruciatingly familiar story. But for most of the film, the Holocaust is merely a backdrop for the main plotline of the intellectual and psychological byplay between Jewish psychiatrist Douglas Kelley and Nazi war criminal Hermann Göering. We learn nothing of Kelley’s religious beliefs or cultural heritage, or whether or how he was affected when assigned to interrogate and psychoanalyze an antisemitic mass murderer. Nor do we gain insight into what allowed a powerful leader like Göering to rationalize and emotionally distance himself from such ghastly crimes.

The most Jewish moment of the movie comes from a supporting character by the name of Howie Triest, a German Jew who escaped to America as a child and returns as an adult to serve as a military interpreter. “Do you want to know why it happened here?” he asks Kelley. “Because people let it happen.”

Triest reminds us that genocide and atrocity don’t happen in a vacuum, but occur when ordinary people stay silent. While that lesson is achingly familiar to American Jews, “Nuremberg” provides a platform to deliver that necessary message to a larger audience when antisemitism is again spreading so rapidly.

The film’s producers also deserve credit for including historical footage of the concentration camps. Most of us are familiar with these unbearable scenes. But much of the audience is seeing those images for the first time. So at least briefly, they are forced to confront the extent of the Nazis’ depravity.

Any book or movie that reminds contemporary audiences of the genocide of the Shoah deserves our gratitude, as it forces the uninitiated to fathom the harsh reality of the slaughter of 6 million Jews. In an almost post-Gaza world, it helps them understand what genocide really looks like.

But the movie that forced me to think more deeply about the lessons of Hitler’s Germany was not a film expressly about holding the Nazis accountable for their crimes, but rather a fantasy musical about witches, wizards and talking animals.

Before seeing the newest installment of “Wicked,” I thought that the idea that even a dramatically remade version of Munchkin-land would evoke troubling parallels to Weimar Germany sounded ridiculous, even blasphemous. (Admittedly, I was prepared in advance for the comparison by reading a strong review from the Forward’s P.J. Grisar.) But underneath the new twists on our childhood memories of Dorothy and Oz is an effort toward more challenging and disturbing questions about fear, propaganda and misinformation that turn a frightened people against an imagined threat.

Grisar writes about how Oz’s fictional demonization and prejudice against animals and Munchkins carried uncomfortable echoes of the treatment that German Jews like Howie Triest’s parents faced. And the often-lighthearted tone of a classic children’s story leaves us unprepared for the anger and hatred that an oppressed underclass must endure. But the lessons are still there nonetheless.

The first “Wicked” movie effectively explained this type of bigotry, using the Wizard to tell Elphaba that “the best way to bring folks together is to give them a really good enemy.” But the sequel goes much deeper and darker, including scenes of the victimized being forcibly removed from departing trains and even held in cages.

The film’s Jewish producer Marc Platt has said that the metaphor of a leader scapegoating a marginalized group deliberately parallels real historical episodes like the Holocaust. Platt believes that the theme of demonizing outsiders in “Wicked” is deeply rooted in Jewish history and memory of persecution. He frames his movie’s themes not as a vague fantasy allegory, but as intentionally resonant with real history of antisemitism.

I have found that the most meaningful nearby location to consider these lessons is the excellent Holocaust Museum of Los Angeles. How improbable that another place to consider the same unfortunate history is a talented Jewish man’s reimagined version of what he saw beyond a yellow brick road.

Dan Schnur is the U.S. Politics Editor for the Jewish Journal. He teaches courses in politics, communications, and leadership at UC Berkeley, USC and Pepperdine. He hosts the monthly webinar “The Dan Schnur Political Report” for the Los Angeles World Affairs Council & Town Hall. Follow Dan’s work at www.danschnurpolitics.com.