Along with so many, I have been crying. Feeling winded. Reeling. A great light has just left our world, and I am deeply mourning the loss of my teacher and guide, Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, Rav Ya’akov Zvi Ben David Aryeh. He changed my life in so many ways, and I loved him for it.

Here’s just one way he inspired me: Rabbi Sacks once told me to start listening to “Hamilton,” started rapping the lyrics, said he had heard the musical at least 30 times. “It’s free if you’ve got Amazon Prime and the book is currently on sale at £19.99,” he specified. It was helpful shopping advice from the most famous living Rabbi in the Western World and one of the great intellects of our time. Naturally, I listened and got hooked on “Hamilton.”

We also talked about Beethoven, Haydn, and Mozart. Eminem was on his most recent playlist. “It’s music that comes from pain,” he said. Around the time of his 72nd birthday this year, I reached out on his behalf and set up a meeting between Rabbi Sacks and Lin-Manuel Miranda, which was due to take place on his planned trip to New York City in September. Since COVID-19 happened, the meeting was canceled and now it will never take place. I also sent him a video of a stage performance I’d recently done of my Hebrew “Hamilton” song (an upbeat retelling of the Passover story set to the opening of “Hamilton”). He sent me a text. “Absolutely brilliant. Looking forward to seeing the finished version! All good wishes. JS”. I’m gutted that he will never see the finished version of the piece he inspired, a production we shot in Los Angeles just 10 days before the first lockdown.

I am devastated that we won’t be able to get together again in person. He had an extraordinary impact on my life, which only continued to grow as the years went on.

The Chief Rabbi’s Grant

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks was Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth from 1991 to 2013. The British Commonwealth currently includes 54 member states, so he technically had a global parish. More official titles followed in 2005, when he became Sir Jonathan Sacks. Then he was elevated to the House of Lords in 2006 and became “Baron Sacks, of Aldgate in the City of London” Yet he signed his emails humbly, without titles. Perhaps this was what made him such a great leader; he never sought power, only to teach and serve.

His spiritual association with Los Angeles began in 1968, when a 20-year-old Sacks was on summer vacation from Cambridge University and stayed with his aunt in Beverly Hills. He received a much-awaited call from the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s office in Crown Heights, New York, saying that he had been granted a private meeting with the Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson. He promptly got a 72-hour non-stop Greyhound bus to meet the great man. The Rebbe encouraged Sacks to get more Jewish students involved in their Jewish life. In a subsequent meeting[1] sSeveral years later, Sacks told me he was considering becoming an academic, economist or barrister, but Rabbi Schneerson told him to become a congregational rabbi and to train rabbis. Schneerson’s legendary prophetic vision undoubtedly saw his potential to become Chief Rabbi.

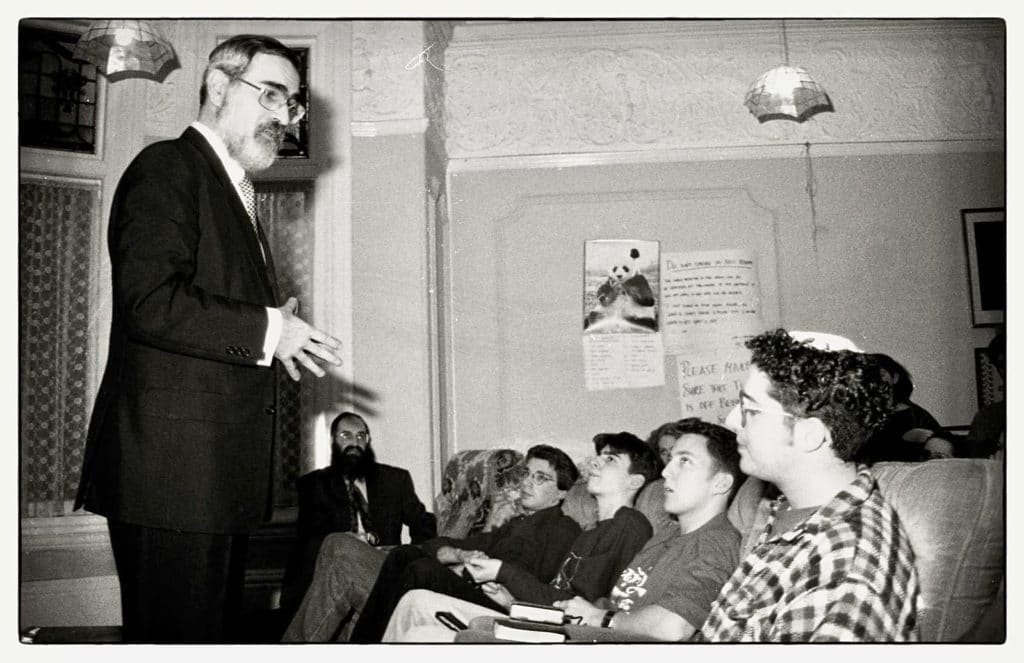

I first met Rabbi Sacks in 1995, when he spoke to the Jewish Society at Birmingham University, where I was an undergraduate. Our group was mesmerized by his teaching, and the following year, I interviewed for a Chief Rabbi’s Scholarship to study at Yeshivat HaMivtar in Israel. The scholarship panel consisted of his first Chief of Staff Syma Weinberg and his office’s Chief Executive Jonathan Kestenbaum (who later became Lord Kestenbaum, also known as Baron Kestenbaum of Somerset).

The one thing the panel asked was that I give one year’s service to the Anglo-Jewish community upon my return from yeshiva, such as teaching at a Sunday Hebrew school. I agreed, but felt some trepidation at my ability to fulfill the promise. Little did I realize that I would embark on a career as a creative Jewish educator that has, so far, spanned 18 countries.

By 1997, I was serving as National Education Director for the United Kingdom’s Union of Jewish Students (UJS). I quickly found myself in a difficult position trying to program speakers for our annual student conference while satisfying the then-warring factions of Orthodox, Masorti (Conservative), and Reform movements. I was at my desk, and someone said “Marcus, it’s the Chief Rabbi on the phone for you.” Rabbi Sacks invited me into his office for a meeting and found a stressed 21-year-old graduate of English Literature of Drama completely out of his depth. “Rabbi Sacks,” I asked, “what do I do?”

He put me at ease, relaxed in his chair, lit his pipe, took a deep breath and exhaled a cloud of smoke. As the smoke cleared, his face was beaming. He said, “Marcus, it’s all nonsense. I’m not a politician. I’m not good at this stuff. Just do your best.” So I did, and it all worked out fine.

Orthodox or Reform?

Four months later, Rabbi Sacks spent Shabbat at the UJS Spring Seminar along with his lovely wife, Elaine. Rabbi Sacks graciously sat through my lunchtime Torah teaching, and on Shabbat afternoon he mixed with the students. A girl came up to him and said, “Chief Rabbi, I’ve just discovered I’m Jewish. Should I be Orthodox or Reform?”

It was an innocent question posed to one of the most brilliant Jewish minds of our time. He responded along the lines of “learn about Judaism and see what speaks most to you.” I loved the inner confidence of his answer, his innate trust in God that truth would prevail, without having to impose a choice on the young student, even though he was the leader of Orthodox Judaism.

This theme continued years later, when I was having tea with Rabbi Sacks at his home in London. He told me about his new BBC radio series and a fascinating conversation he had with Professor Jordan Peterson, and another leading Jewish academic who is an atheist. “Did you try to mekarev him? (make him religious)” I asked. “Absolutely not.” “What was your objective?” I enquired. “It is good for someone to have a friend who is a religious Jew.”

I found this story powerful for many reasons, including how it teaches the value of promoting a Torah-observant lifestyle through non-judgmental relationships. We can learn Torah from traditional writings but also from the actions of our sages. As Rabbi Sacks would say, “there are text books and there are text people.”

Limmud

Jewish community politics can become a firestorm, and British Jewry’s hot topic in the late 1990s was the Limmud Conference, a flagship cross-communal festival of Jewish ideas. I first attended in 1993, when it was a small conference of 250 educators, but it now comprises 93 international satellite communities. Limmud began in Great Britain, but the Chief Rabbi was unable to attend due to pressure from the Beit Din, which believed his attendance would endorse non-Orthodox movements.

Every September, Rabbi Sacks hosted a private pre-Rosh Hashanah class for our cadre of young Modern Orthodox educators. We visited the Chief Rabbi’s residence in St John’s Wood, close to the famous Abbey Road, and ate smoked salmon and bagels while he shared Maimonides’ teachings on repentance. Someone asked, “Chief Rabbi, can I go to Limmud?” His answer was unequivocal. “Absolutely. You can do what I can’t. When I walk in certain places, landmines explode. Go with my blessing.”

Sixteen years later, Orthodox participation was no longer a major issue, and in 2013, one of the first acts of the newly-appointed Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis was to attend Limmud. Times change. And Rabbi Sacks was ahead of them.

Sacks’ Creativity

Creativity was always a major part of Rabbi Sacks’ leadership. He frequently launched new initiatives and once told me that he wanted to do even more. I remember a Shabbat in the mid-2000s, when I saw him at the Kiddush following services at St John’s Wood shul. “Marcus! What are you up to?” I filled him in on my latest exploits: touring Europe teaching my “Kosher Sutra” yoga and performing one-man Biblical comic plays. He looked at me seriously. “Marcus, don’t let Judaism become boring.” I accepted my mission.

Creativity was always a major part of Rabbi Sacks’ leadership. He frequently launched new initiatives and once told me that he wanted to do even more.

Rabbi Sacks not only recognized these different ways to connect with God but also celebrated and encouraged them. In doing so, he gave me tremendous chizuk (strength, affirmation, motivation, and inspiration).

He occasionally spoke of the differences between Ancient Greece and Biblical Judaism. The former was a culture of the eye, since the Greeks built statues, great art, and beautiful architecture. Judaism, he said, is a culture of the ear, with our key prayer being the Shema (Hear O Israel) and our emphasis on listening to the Torah rather than gazing at a visual image. In a public lecture at the University of London in 2001, Rabbi Sacks described the visual aspects of Greek culture and asked, “In Judaism, where’s the art? Where’s the architecture? Where are the paintings? Where’s the drama, the theatre? There isn’t any. And this is fascinating because this shows us that Judaism is a culture not of the eye but of the ear.”

I raised my hand and asked, “What about the tradition of theatrical Purimspiels? What about the Talmud’s discussion of aesthetics, where it says that a beautiful man is someone with a beard (Bava Metzia 84a) or the beautiful passage where it says that comic actors/jesters will inherit the world to come because they cheer up people who are depressed? (Taanit 22a)” Besides that, I noted, dismissing the visual arts was bad for my business!

Rabbi Sacks took it in the friendly-but-serious way I’d intended it, and immediately responded with perhaps the most beautiful compliment I ever received. He said, “Marcus. Listen! Of course, you are doing great stuff here. You’re doing the Jewish thing! Marcus, amongst his many talents, is a playwright and dramatist and actor-manager and all the rest of it.”

It may be profoundly immodest and un-British that I’ve shared this, but it was such a striking contrast with all of the Rabbis who had said to me over the years that I should just use my acting skills for teaching drama lessons at Hebrew school. That may be one application, but Rabbi Sacks saw the bigger vision. “Judaism is drama,” he said. “But it is not drama on the stage. But now we are in a culture where we have to use that instrumentality, and I am in favour of using all cultural instrumentalities. What I think Judaism misses most right now is a first-rate religious film director. A first-rate religious poet.”

He then went on to pronounce, “Marcus, I say: Use your many, many wonderful talents to bring a Jewish presence to the arts. I will even give you ‘Certified under Chief Rabbinate supervision’ — not that it will do very much for you!” It got a great laugh, but he was wrong. His encouragement inspired my work for years to come, eventually leading me to move to Pico-Robertson, where I found my tribe of professional, Shabbat-observant artists. Rabbi Sacks’ tenure as Chief Rabbi was dedicated to creating the “nation of leaders” that prophet Elijah spoke of, allowing us to be who we are and encouraging us to realize our highest individual potential. (The full transcript of this conversation can be found at: https://rabbisacks.org/covenant-conversation-5768-vayakhel-the-beauty-of-holiness-and-the-holiness-of-beauty/)

I was once a little envious when he told me that his recent dinner guest was Sir Mark Rylance, one of our most accomplished theatrical knights. At other times he met with Archbishops, Heads of State, and world experts in many disciplines. None of this was for personal gain, but all of it was part of his mission to fulfill the prophet Isaiah’s mission of being a light unto the nations.

Liberation

The most life-changing conversations I had with Rabbi Sacks took place at the end of 2017. I had been discharged from Cedars-Sinai hospital after having two emergency brain surgeries following a near-death experience of being hit by a car while walking to a Shabbat dinner. Rabbi Sacks called to wish me a refuah shlemah (complete healing) and offer support. He told me that just as Jacob had wrestled with the angel and emerged a changed man with the new name ‘Israel,’ I too had wrestled through the night and changed my name; he hinted that I would be all the stronger for it. “But now is the time to do yourself chesed,” he advised.

We spoke a few weeks later, and I shared my turmoil about that name change, which took place when I had passed my Rabbinical exams. I was immediately criticized by the governing authorities for not being religious enough. “Don’t chase titles,” Rabbi Sacks said. “They won’t help you. Marcus, you are a free spirit and you are meant to be free.” In that last sentence, it felt like he had seen into the depths of my soul, understood my essence, and gave me permission to be myself.

Rabbi Sacks taught me how to be Freed.

The Chumash

In 2017, Rabbi Sacks was working on his translation of the Chumash (his edition will probably become the key version used worldwide for the next hundred years). I enquired how it was going, and he responded, “don’t ask!” When we met in 2018, I asked again and his slightly frustrated response was “I’m currently writing three other books that are under contract and on deadline.” Presumably that’s part of the deal once you are a brilliant bestselling philosopher in high-demand, I thought.

I once asked Rabbi Sacks how he was dealing with this growing public spotlight, and he told me of a recent trip to Israel, where he spoke at the Great Synagogue in Jerusalem and was met by over a thousand admiring fans. “They want to put me on a pedestal. Historically, these things do not end well. I want no part of it.” He knew that fame is fickle, public opinion can always change for the worse, and his unspoken humility dictated that his work was about God and the Torah, never about himself. The mission was teaching and not becoming a celebrity.

Ironically, the only way that public opinion changed about him was to increase his popularity and influence during the last decade of his life.

Our Final Meeting

Our final meeting was on January 22, 2020, in the lobby of the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Rabbi Sacks was in Los Angeles for a 48-hour-visit, but found time for a cup of tea just before leaving for the airport. This memory brings me the most joy but also great sadness for all that was begun but not completed. He asked how the accident, brain surgery and near-death experience had changed me. I explained how it had awakened and focused my attention to my true mission in life, made me aware of my relationship with time, and convinced me of the need for fast action.

I asked his advice on getting married, since building a family is something I want more than anything. “How are old are you now?” he asked. “44.” The man of a million words then gave me four: “Get on with it!”

“What do you advise to look for? I keep getting attracted to women who are not good for me,” I said. “Find someone who is kind and understands you. The rest is icing on the cake.”

He spoke glowingly of his wife Elaine, who has been very warm whenever we have met at events or when I would visit their house for tea. “I married Elaine young. She was the breadwinner while I was studying to become a Rabbi.” In a recent podcast with Tim Ferris, Rabbi Sacks said, “Elaine is a happy person.” What more can one ask for in a partner?

I said that one day, I look forward to calling him up and asking him to be metzadei kiddushin (officiant) at my wedding. He nodded.

As our meeting ended, I walked Rabbi Sacks and his Chief of Staff Joanna to their airport taxi and carried his bag. He started quoting “Hamilton.” “Marcus, don’t throw away your shot. This the room where it happens.” I replied, “Rabbi Sacks, I’m looking forward to reading your Chumash. No pressure, but history really does have its eyes on you.”

He cracked up laughing and gave me a massive hug. I’ll miss him.

“Light is sown for the righteous, and joy for those with an upright heart” (Psalms 27:11). Rabbi Sacks brought great light into the world and today it shines more brightly than ever before. May his soul rise ever higher.

Marcus J Freed is an award-winning actor and bestselling author. Online at www.marcusjfreed.com and on social media @marcusjfreed.