On the fourth Thursday of each November, we gather around a table laden with turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce, and pie, and we tell a story:

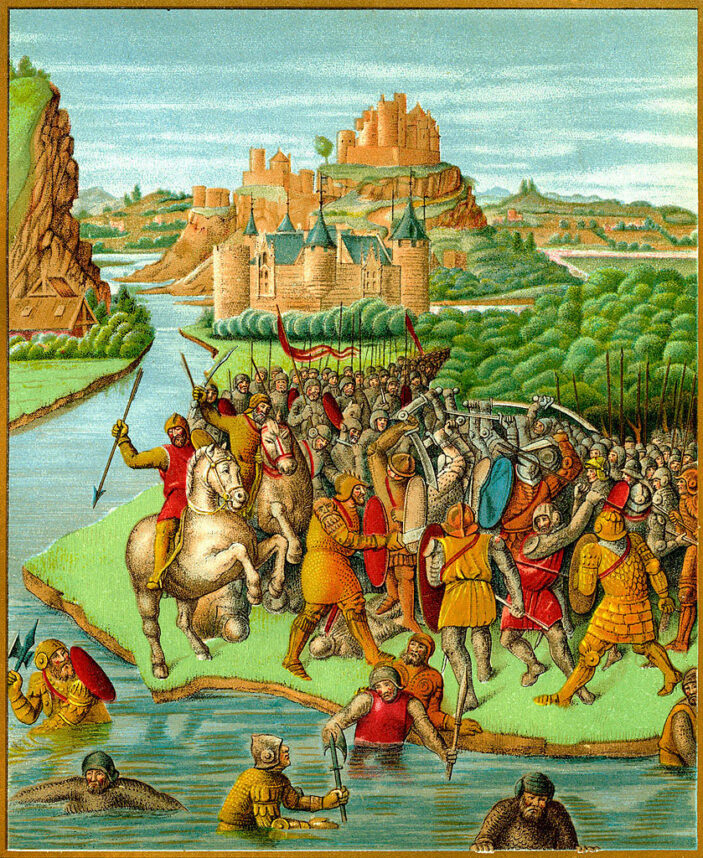

In 1620, our Pilgrim ancestors escaped the tyranny of the Old World and braved a treacherous journey to find freedom on the shores of this virgin continent. Landing at Plymouth Rock, at the edge of a vast wilderness, they nearly starved but were saved by gracious natives who brought food and techniques to cultivate local crops. Later, their survival ensured, our ancestors sat down to a feast of Thanksgiving, in gratitude to the natives and to a providential protecting Deity. And so we gather every year to share our appreciation and our blessings.

Is the story true?

In 1620, my ancestors were starving in Poland. Had they, by some miracle, arrived in the Plymouth colony, they likely would have been tossed out. The Pilgrims sought religious freedom for themselves, but they were loath to extend it to others. Then there’s the story’s unfortunate end: Following dinner, once the dishes were washed and grace recited, the newcomers brutally dispossessed the natives and stole the continent.

Does it matter that the story is wanting historically? It is true in a deeper way. This is the story that makes us Americans. To be an American is to tell this story in the first person and in the present tense. Who are we? We are people escaping tyranny and persecution. What do we seek? The freedom to live our lives and worship God as we choose. Where have we come? To a virgin continent, overflowing with resources and possibilities, awaiting our creative designs and energies. We have come to a New World, unfettered by the corrupting prejudices and authoritarianism of the past. We are not refugees, not immigrants, but Pilgrims on a sacred journey to a promised land in fulfillment of God’s will.

The story reveals the American soul: our love of liberty; our suspicion of government’s power; the belief in our manifest destiny to conquer and lead the world; our sense of ourselves as free children of a New World.

It may be the congruence between this American story and the Jewish story that makes us feel so at home here. We recognize these themes as our own — the escape from tyranny to freedom, the perception of God’s will in our destiny, our gratitude for these blessings. And how fortuitous that on Thanksgiving the Pilgrims didn’t serve ham!

Stories matter. We tell stories, and they shape us. Through stories, communities are built. Stories shape national identity and values. Stories capture and convey the meanings and purposes we find in life. To be an American is to tell the Thanksgiving story as my own story. To be a Jew is to tell the Jewish story.

This week’s Torah portion retells the Jewish master story. “My father was a wandering Aramean. He went down to Egypt in meager numbers and sojourned there; but there he became a great and very populous nation. The Egyptians dealt harshly with us, oppressed us and imposed heavy labor upon us. We cried to the Lord, the God of our ancestors, and the Lord heard our plea and saw our plight, our misery, and our oppression. The Lord freed us from Egypt by a mighty hand, by outstretched arm and awesome power, by signs and miracles. He brought us to this place and gave us this land, a land flowing milk and honey” (Deuteronomy 26:5-10).

This is our story. We repeat it at the Pesach seder, at our festivals, in our daily prayers because this story establishes our identity as a people: We are the products of a unique experience — Pharaoh’s slavery and God’s liberation. It describes our ethics, our theology, our communal mission to bring the world out of Egypt. It offers our life metaphor: We are always on the journey from Egypt to Canaan, from the house of bondage to the Promised Land.

God created man, wrote Elie Wiesel, because He loves stories. And it is by stories that we are created as individuals, as Americans and as Jews.

Ed Feinstein is rabbi at Valley Beth Shalom in Encino.