“What Does Hollywood Owe Its Jewish Founders?” wondered a recent headline in the New York Times as the controversy continued regarding the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures having neglected to include Jews in its portrayal of the emergence of Hollywood when the museum opened in 2021. Despite the founding forces of Warner Brothers, Universal, Columbia, Paramount, 20th Century Fox, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer being Jewish, most of them immigrants, this was somehow not part of the history the museum set out to tell. Its former director Bill Kramer denied to the Times that this had been in error, admitting only “it was clear that this was something that certain stakeholders were expecting.” This after a Hollywood historian told Rolling Stone that leaving the Jews out of the story of the film industry was “sort of like building a museum dedicated to Renaissance painting and ignoring the Italians.” Thankfully, a new permanent exhibit, “Hollywoodland: Jewish Founders and the Making of a Movie Capital,” was added and opened last month.

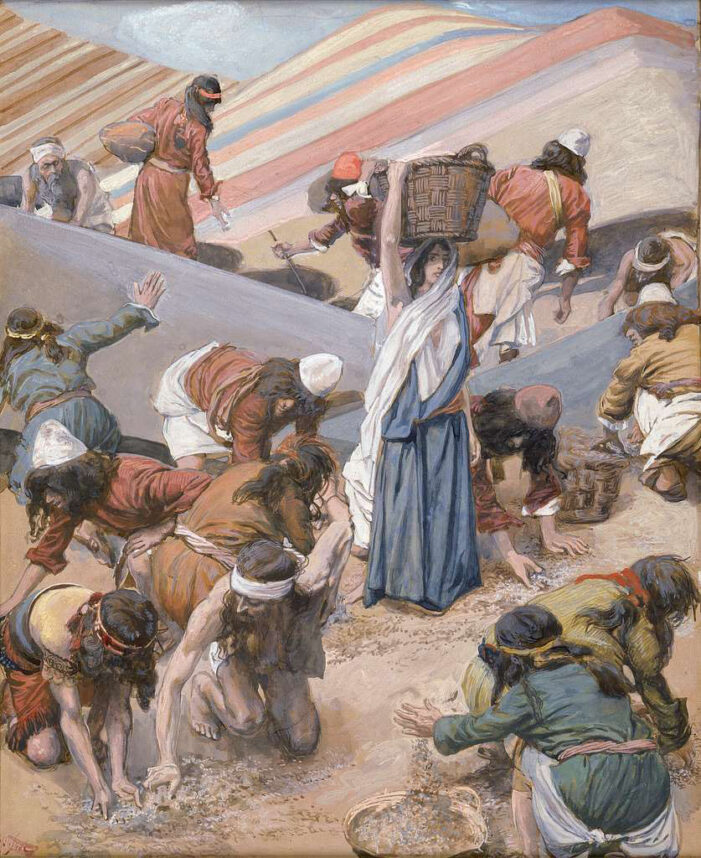

As Jews continue to navigate antisemitism from Hollywood to the Holy Land, we can draw inspiration from a very different Jewish founder, the biblical figure of Ruth, whose story we just read on the holiday of Shavuot. A remarkable figure, Ruth was a Moabite married to one of the sons of Naomi, an Israelite from Bethlehem who lived during the period of Judges, which followed the death of Joshua, Moses’ successor. After the passing of their respective husbands, Ruth accompanied Naomi back home in an act of selfless loyalty, proclaiming “Wherever you go, I will go… Your people shall be my people and your God my God.” Back in Bethlehem, Ruth met and eventually married Boaz. They produced a child, reviving the family line and the psychological spirit of both Ruth and Naomi.

Ruth acts, in her starring role, as a foreign refounder of the Children of Israel. Though our patriarch Abraham is credited rightfully with being history’s first Jew, Ruth’s actions both mirror and perhaps even supersede those of the patriarchal predecessor’s initial journey to the Promised Land. As literary scholars have pointed out, Ruth’s actions bear a striking similarity to Abraham’s:

Both head to the land of Israel despite an uncertain future — Abraham by God’s command and Ruth simply out of generosity of spirit.

Abraham is promised that upon arriving there he will be a great nation, blessed and of strong societal standing. Ruth is offered no such reward, and Naomi even attempts to dissuade her from coming at all.

Abraham sets out with both wife and wealth in tow. Ruth is a destitute widow.

As the Bible professor Yair Zakovitch has put it, “This inverted comparison between Ruth and Abraham testifies that this Moabite woman, who knows no selfishness, who leaves her country out of commitment to her mother-in-law with no hope to become a mother herself, is a more noble figure than the nation’s father, Abraham.”

As a coda to Ruth’s commitment to Naomi, the Book of Ruth ends with a genealogy. It reveals that Ruth’s son Oved’s descendant was none other than King David, the paradigmatic poet-prophet monarch, for whose kingdom’s restoration in the form of the Messiah Jews pray three times a day. “The foreignness of Ruth is what enables her to supply the Israelites with a refurbishment they periodically need,” observed the political philosopher Bonnie Honig, “she chooses them in a way that only a foreigner can … and thereby remakes them as the Chosen People,” setting in motion the redemption of the world. Her act of kindness helped Israel emerge from its period of disarray and divisiveness and head towards a kingdom blessed by the divine.

Though they were hardly of the spiritual status of Abraham or Ruth, Hollywood’s founders saw in their creation an ability to write new stories, both for their new country and themselves. As the Times notes, citing Neal Gabler’s 1988 book, “An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood,” Louis B. Mayer, a co-founder of MGM, claimed that his birth papers had been lost during his emigration from Russia and declared his birthday would now be the Fourth of July. To these founders, Judaism was incidental, perhaps even a hindrance to the new tales they wanted to tell. The Academy Museum’s initial effacement of Jews, then, continued its industry’s preference for rewriting its roots.

Standing thankfully in contrast is Ruth. Arriving as a foreigner, she proudly proclaimed loyalty to the Jewish faith and Jewish people. Deeply dedicated to her Judaism even in the most fraught of times, her commitment to God’s covenant with the Jewish people authored a story that continues to shape history more than any Hollywood blockbuster, or museum, ever will.

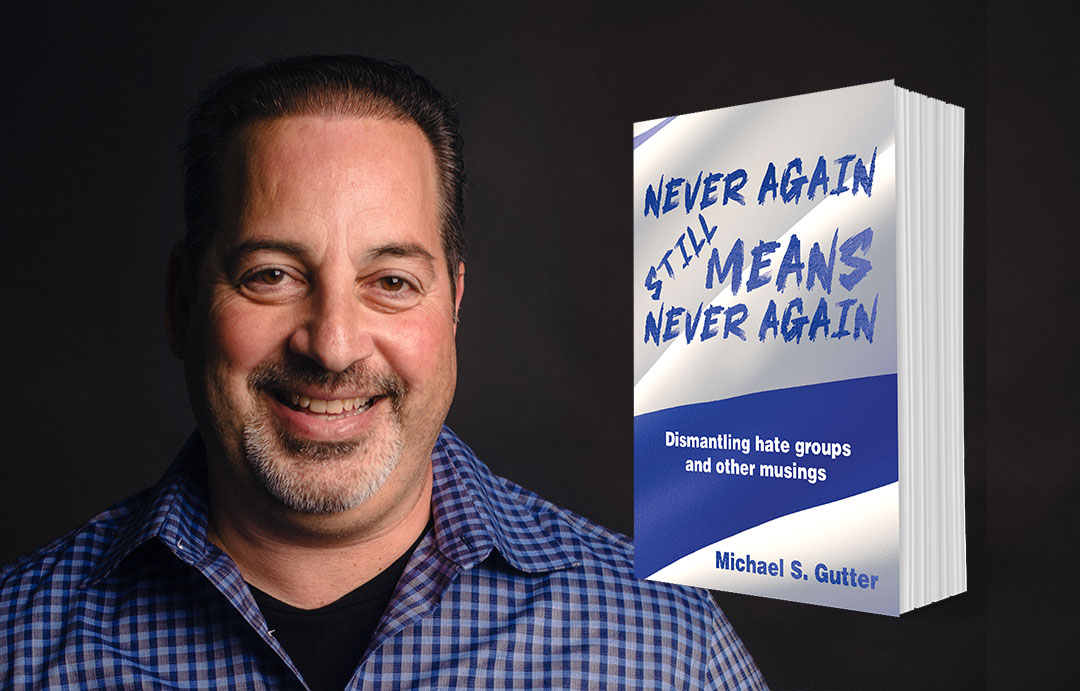

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.