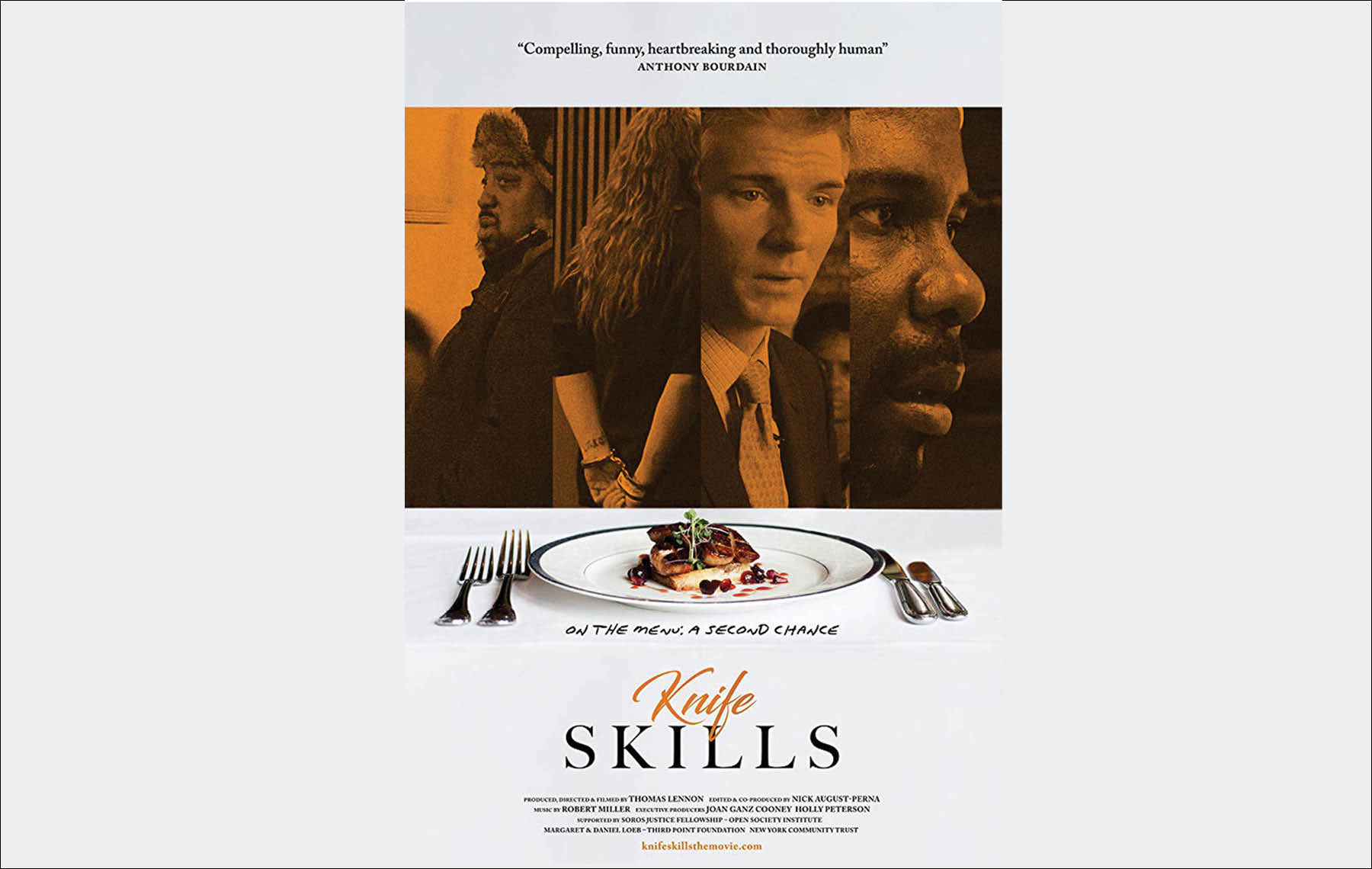

From left: Tony Jones, Vatasha Tucker, Brandon Chrostowski, Courtney McKinney and Derick Seals.

From left: Tony Jones, Vatasha Tucker, Brandon Chrostowski, Courtney McKinney and Derick Seals. Have you ever had a dream in which you’re unable to move or get your vocal cords to work? No matter how hard you try to scream or how much you struggle to utter a word, you simply cannot. For most of us, these stress dreams point to a metaphorical lack of control or a feeling of being ignored or overlooked and, although unpleasant, usually fade within a few minutes after awakening.

But for inmates released from the U.S. prison system trying to assimilate back into society, this feeling is a living nightmare, leading to an almost 50% chance that they will reoffend during the first year after their release. And although the first year out of prison features the highest rates of recidivism, the percentage of ex-convicts returning to prison within three years of their release is also shockingly high.

This is the subject of an unexpectedly touching documentary exploring a world that is unknown to many viewers; a humbling, throat-catching, sometimes difficult to watch but ultimately uplifting journey through the eyes of a collection of newly released prisoners and their fiercely passionate teachers and leader. The film focuses on the ex-prisoners six weeks before they graduate from a program designed to teach them skills in the world of fine dining. It follows their struggles as they try to navigate the frenzy of opening a high-end French restaurant called Edwins in Cleveland.

“Knife Skills” (2017), is the brainchild of documentary filmmaker Thomas Lennon. He was inspired at a dinner party at friends David and Karen Waltuck’s apartment. The husband-and-wife team who for 30 years ran Chanterelle, one of New York City’s most influential restaurants, introduced Lennon to one of the restaurant’s former dining room managers named Brandon Chrostowski, who told the guests about an idea he had.

Midway through his time at Chanterelle, Chrostowski incorporated a nonprofit called Edwins, which, according to him, would be “the very best French restaurant in the country, staffed almost exclusively by people coming out of the justice system.”

“Brandon had such ferocity of purpose. He’s a force of nature — he was not going to be denied.” — Thomas Lennon

Chrostowski insisted that one of the keys to keeping ex-cons out of prison was to find them jobs that paid enough to maintain a living. But because businesses prefer to hire people with no criminal record, these highly vulnerable individuals face a catch-22 situation that often can lead to problems and risk of a relapse.

Lennon was intrigued by Chrostowski and his passion of purpose. “Here’s this young guy, a former inmate, a gritty working-class kid from Detroit, raised by a single mother, who goes to the Culinary Institute, becomes a chef working in some of the most exclusive restaurants in the world, and then decides to become a nonprofit entrepreneur. He had grit but more than that, it was his calling.”

Chrostowski recalled Lennon saying to him, “Look, man, if it’s a bust, it’s a great movie; if it’s a hit, it’s a great movie.”

But Lennon confessed to being nervous initially to take on the project. “Documentary filmmakers are generally driven by the impulse to do good in the world, to make an impact and shed light on a topic,” he said, “but the ‘do gooding’ impulse can propel you into a project that’s a train wreck, and it’s often only after months and years of work that you even know if it was worth it.”

As much as his curiosity was piqued, Lennon was unsure if it was wise to make that investment based on one conversation with the tough-talking Chrostowski. It wasn’t until Lennon went to Cleveland to research the program that would launch Edwins’ opening, that he knew he had to do the film.

“Brandon had such ferocity of purpose. He’s a force of nature — he was not going to be denied,” Lennon said. “I realized I wanted to illuminate people who have no voice, to bring people here and plunge them into an improbable universe to think about the issue of reentry.”

Indeed, the film compels viewers to think about the challenges of its protagonists but also leaves room to draw conclusions, which is one of the film’s great humanizing forces.

Despite a long career in film that has earned him an Academy Award and multiple Oscar and Emmy nominations, Lennon said making the film was a challenge. He and Chrostowski almost came to blows several times, and co-editor Nick August-Perna, who also co-produced the film with Lennon, agreed that it was the hardest editing job they’d ever done. Still, Lennon said, “Despite the challenges, Brandon was the person making everyone move. He was the catalyst.”

The film begins six weeks before the restaurant’s opening night as Edwins’ first graduating class is fitted for chef’s jackets, and then delves into their struggles as they learn — from two heavily accented French chefs — how to prepare the 25 classic French dishes on the menu. Trainees also take crash courses from Chrostowski in French wine and cheese pairings as well as restaurant finance.

It’s a high-pressure rehabilitation program and not everyone can handle the demanding schedule or the level of discipline. Unsurprisingly, out of the 70 men and women who enter the program, that number dwindles to fewer than half for a variety of reasons: Some drop out on their own, others are pulled out by Chrostowski. Cooks, servers and bartenders, must become familiar not only with the food and wine but their origins along with the correct French pronunciation. For some, it’s their first exposure to the restaurant business and, for many, their first glimpse into the world of fine dining.

For those in the business who have lived through the chaos of a restaurant opening, it’s difficult to fathom the seemingly impossible task of guiding newly released inmates, many with past and present struggles with addiction, post-traumatic stress disorder and childhood trauma, through something as perilous and ambitious as the launch of a fine French dining establishment, and the film’s viewers discover the challenges the trainees face after their release.

“It’s just hard work,” Chrostowski said. “It’s all about giving people confidence. As a kid, I was in jail twice, and if it wasn’t for a judge who gave me 10 years’ probation and allowed me to stay out of jail for the third time, I don’t know where I’d be right now.”

“If it wasn’t for a judge who gave me 10 years’ probation and allowed me to stay out of jail for the third time, I don’t know where I’d be right now.”

— Brandon Chrostowski

Lennon managed to capture the raw and sometimes bitterly honest interviews with the program’s participants as well as their emotional fragility and the big hearts of those in charge. In essence, this is what “Knife Skills” is about — imperfect people going above and beyond to give redemption to others who desperately need a second chance when they have been all but forgotten by the rest of the world, in some cases even by their families. What joy viewers feel for one of the graduates when he impresses his cooking-show obsessed mother with stories and photographs of his French mentors and his newly learned skills.

In these moments, which are abundant in the film, viewers get a glimpse of what drives Chrostowski to achieve the seemingly impossible and to never accept failure as an option.

“Human beings amaze me — we can do anything,” he said, his voice cracking a little. “Once people realized what we were trying to do here, that everyone deserves a fair and equal future regardless of their past, it was incredible how the peripheral community contributed to the project.”

He added that 15,000 donors pulled together sums big and small and offered their time, expertise and support to ensure the program was a success.

In total, Edwins received more than $200,000 from foundations and individuals. One day, Chrostowski received an anonymous check for $50,000, but nothing prepared him for the envelope filled with $4 in coins from a 9-year-old who mailed Edwins her entire allowance along with a note of thanks.

Although “Knife Skills” was a success, earning an “Audience Favorite” award at Michael Moore’s film festival in Michigan as well as the ultimate accolade, an Academy Award nomination, Ed Levine, a bestselling author and founder of Serious Eats website, summed up the film’s success saying, “I’ve seen that movie 10 times and it still gets me. In many ways, I think the beauty of the film is that Lennon lets the stories reveal themselves and never passes judgment. There’s so much humor amidst the struggles. At one point, we are riding along with this ex-drug dealer who completely surprises by quoting Shakespeare — ‘Oh, what a tangled web we weave when first we practice to deceive.’ ” Levine laughed when recalling the scene and then summed up the film. “It’s just a perfectly told story and I still cry every single time I watch it.”

Chrostowski has graduated hundreds of ex-convicts. He now runs a six-month training program in prisons, which has grown to include the restaurant, on-campus housing for his trainees and, recently, a full-service butcher shop he opened in Cleveland’s Shaker Square.

According to Chrostowski, the biggest challenge is the saddest one, too. Some students clash with the foreign world of classic French fine dining, some are cut for insubordination, while others reoffend even while working through the program.

Still, he said he has faith in every student, even when they have little to no faith in themselves. “The biggest challenge has been to help build self-esteem in a man or woman who has had it ripped away during incarceration or because of poverty or childhood trauma.”

Chrostowski said that he, too, is haunted by his struggles with his past and self-esteem issues. “I feel like a piece of s— most of the time, like I don’t deserve anything good.”

And with that, the veil of false bravado abruptly dropped and it became impossible not to appreciate the necessity of community, the kindness of strangers and the undeniable knock on positive effect of second chances.

Yamit Behar Wood, an Israeli-American food and travel writer, is the executive chef at the U.S. Embassy in Kampala, Uganda, and founder of the New York Kitchen Catering Co.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.