Planning a visit to a museum always is a major challenge to the ambitious art lover. How many works of art can we hope to see? What should we see first? What can be safely saved for last? And what can be omitted without regret if time and energy run out?

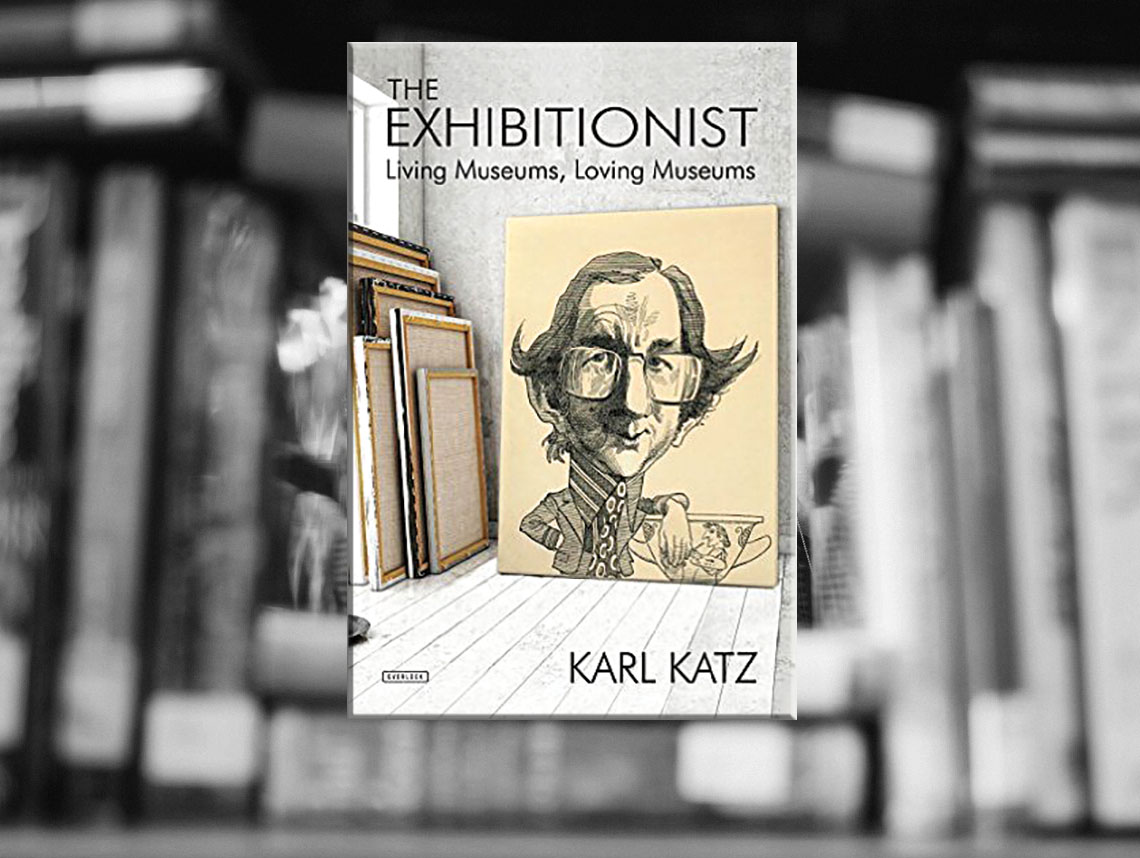

Karl Katz is someone who considered all of these questions from an insider’s point of view. A seasoned planner, designer, curator and director of museums, he helped to create the Israel Museum and was the long-serving chairman of special projects at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. His goal in “The Exhibitionist: Living Museums, Loving Museums” (The Overlook Press) is to reminisce about his own colorful career and, at the same time, to offer “a narrative field guide on how to make museums come alive.”

Like every museum professional, he has come to know the rich and powerful, ranging from Jackie Kennedy Onassis to the mayor of Jerusalem. But he is unimpressed by celebrity. “[A]n architect like Frank Gehry can make a museum a landmark before a single piece of art is installed,” he writes. “But few books pay attention to the people who make museums: the directors, curators, designers and educators who shape each collection of objects and ideas into an institution.”

Raised in Brooklyn, educated at Columbia and deeply inspired by a visit to Israel in 1950, his first opportunity in the museum world was an invitation to participate in a show called “From the Land of the Bible” at the Metropolitan — “an exhibit we called by its unfortunate acronym, FLOB.” He felt a little lonely there: “When I arrived in 1953, I felt like the only Jew in the building — there certainly weren’t matzoh in the dining halls on Passover.”

Then he joined an archaeological expedition in Israel, where he quickly realized the Hebrew he had learned in the yeshiva was not the same as the lingua franca of the Jewish homeland: “[M]y language was speckled with the Hebrew equivalent to old English’s thees and thous.” But it was in the Middle East that he acquired firsthand expertise in the acquisition of museum-quality antiquities, not only in Israel but also in Egypt, Turkey and Iran.

Thus began his museum career. He was recruited as the director the Bezalel National Museum, which had been Israel’s first museum, and then he was approached by Teddy Kollek, the future mayor of Jerusalem, to join the planners of what would become the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. The challenges went far beyond the ordinary concerns of collectors and curators of art — for example, the preferred site for the new museum presented strategic concerns. Yigael Yadin, a famous general who was just as well known for his accomplishments as an archaeologist, “was afraid that artillery from Bethlehem would find a sprawling hilltop complex an easy target.” Katz recalls the planning committee “finally convinced him that if the Arabs were going to shell anything, they would shell everything, and he gracefully backed down.”

Katz was lured back to New York after the opening of the Israel Museum when he was invited to accept the directorship of the Jewish Museum on Fifth Avenue. One of his mentors, rabbi and archaeologist Nelson Glueck, advised him to take the job: “Karl, you’re a showman, an exhibitionist.” Even so, Katz ran into opposition from the conservative members of the board of trustees when he proposed a show about the 1968 protests in Paris and Prague, and an even more heated response to an exhibit on Purim that placed the holiday in its historically accurate Persian setting: “To them Persia meant Islamic, and ours was a Jewish museum.” When he first proposed to open the museum without charging admission on Saturdays, as was done at the Israel Museum, “I hit a solid wall of no,” although the board later relented.

The breaking point came when the board of the Jewish Museum, which was unhappy with Katz’s interest in contemporary art and social controversies, resolved to return to presenting only exhibits with strictly Jewish content, a restriction that forced Katz to resign. Ironically, he returned to the museum where his career had started — the Metropolitan, whose director, Thomas Hoving, had taken notice of “all these fabulous shows at the Jewish Museum.” Once again, Katz was ranging around the world in search of art treasures, an effort that brought rare loans from China and the Soviet Union to New York City.

Yet it was a much sought after loan of the Book of Kells from Ireland in the 1970s that presented the biggest obstacle. According to a belief that was shared by the Irish archbishop whose blessing he needed to borrow the Book of Kells, no male children would be born if the medieval manuscript was no longer on Irish soil. “Actually, your eminence, when the Book of Kells went to England in 1953 to be rebound, plenty of Irish boys were born,” Katz boldly replied. The archbishop was persuaded and the exhibit at the Met was so successful that it toured across the United States. The goal of the exhibit planners, in the words of Irish professor G. Frank Mitchell, had been achieved: “We hope to implant in the American mind the idea that Ireland can create more than bombs and bullets.”

The Met and the Israel Museum may be the jewels of his curriculum vitae, but even more remarkable are the reach and diversity of his long career, all vividly and charmingly revealed in the pages of “The Exhibitionist.” Katz played a role in the design of the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, for example, as well as the P.T. Barnum museum in Bridgeport, Conn. — a fitting assignment for a man who embraced and embodied the role of the showman.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.