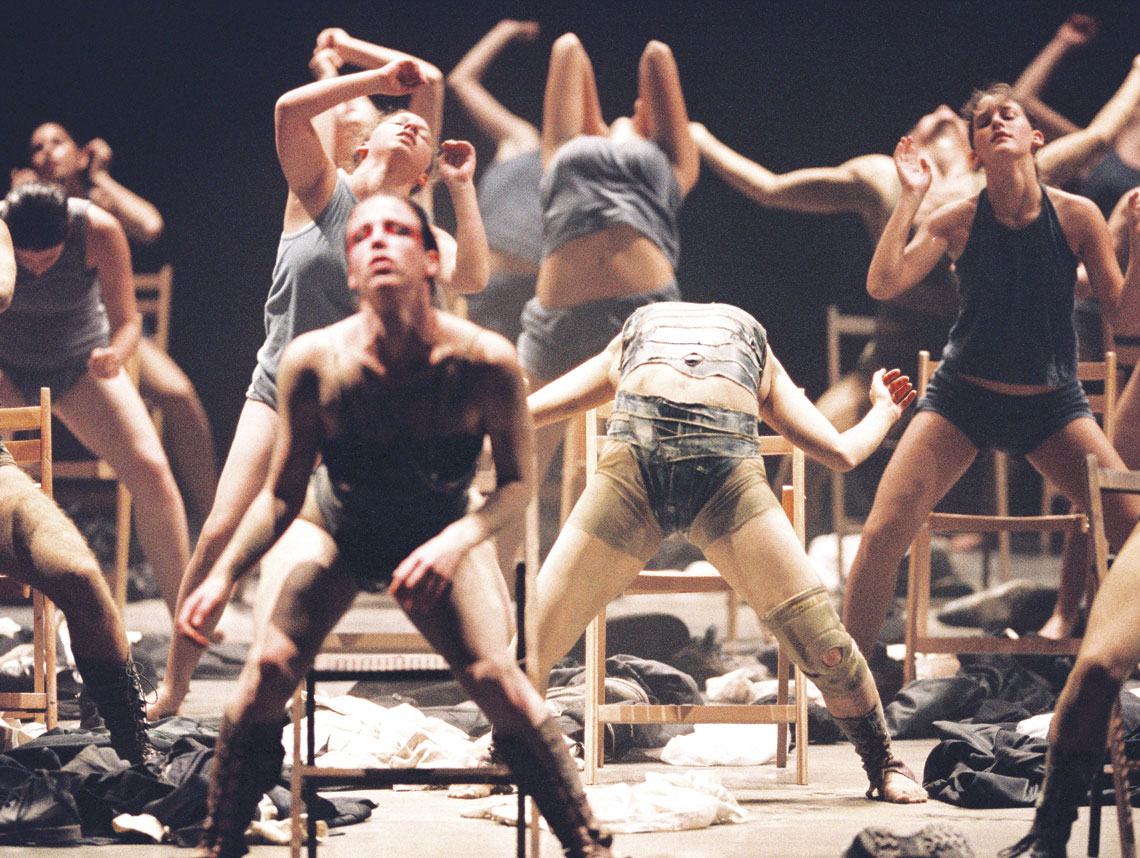

Batsheva Dance Company is the subject of the documentary “Mr. Gaga.” Photo by Gadi Dagon-Anaphaza

Batsheva Dance Company is the subject of the documentary “Mr. Gaga.” Photo by Gadi Dagon-Anaphaza Batsheva Dance Company is one of Israel’s highest-regarded cultural institutions. The experimental dance ensemble, founded in 1964, has riveted audiences around the world. The company’s artistic director, Ohad Naharin, took charge in 1990 and revitalized the company with his unconventional choreography.

A new documentary, “Mr. Gaga” tells Naharin’s life story using never-before-seen archival footage, beautifully shot videos of Batsheva’s performances, interviews with dance critics and former Batsheva dancers, and behind-the-scenes glimpses into the company’s artistic process.

“Mr. Gaga” will screen Feb. 11 at Laemmle’s Monica Film Center in Santa Monica. The screening is sponsored by the Y&S Nazarian Center for Israel Studies at UCLA and will be followed by a Q-and-A with the director of the film, Tomer Heymann. (Three days earlier, on Feb. 8, Batsheva will perform “Decadance 2017,” a repertory program of the company’s celebrated works, at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa.)

The film’s title comes from a movement language that Naharin developed to expand the possibilities of dance and promote physical healing. It’s what makes Batsheva’s choreography so radically different from other contemporary dance. Gaga dance classes are offered to the public around the world, including in Los Angeles.

The film was a labor of love for Heymann. He worked on it for eight years, collecting about a thousand hours of footage and spending roughly $1 million to make it. He fell in love with Batsheva after joining a relative — reluctantly — to see a performance in 1991.

“This guy basically opened me the door, opened the gate, to a beautiful world of dance,” Heymann said. Years later, he approached Naharin with the idea of making a film about him. Naharin refused. It took years of convincing to get his approval.

Naharin has said that if he had made the documentary, it would have come out much different. For one thing, he said in a phone interview, “I would never make a movie about my life. Maybe I would do a movie about my dance.”

Allowing Heymann to tell his life story without creative control over the project was a challenge, Naharin admitted, but handing over that control “came out of a very simple way of how I live, which is, I live as if I have nothing to hide. And that gave him and me the freedom to collaborate.

The theme of control comes up often in the film. In an opening scene, Naharin repeatedly instructs a dancer to fall to the ground. “Way too much control,” he tells her. “You need to find a way to let go.” The ability of the dancer to allow herself to fall without trying to catch herself requires, paradoxically, an enormous amount of control.

“I believe in control; I don’t believe in losing control,” Naharin said.

“I think one of the most important aspects of dance is that you are aware and in control of what you’re doing. And even the sense of freedom, and explosiveness, and even chaos, need to be done in a controlled environment so people don’t hurt themselves or other people.”

Traditional ballet dancers appear lighter than air, their bodies twirling and leaping with a seemingly effortless grace. Batsheva dancers are known for their intense physicality and flexibility, often holding difficult poses for long stretches of time.

“Mr. Gaga” takes us inside the practice space where the dancers participate in grueling rehearsals. Naharin refuses to allow mirrors in the dance studio, to keep the dancers from feeling self-conscious. Similarly, he was resistant to let Heymann film there.

“It took me a very long time to build the trust,” Heymann said. “And Ohad, I can understand his point. He told me, ‘Tomer, I’m afraid that once you’re coming with your cameraman, it will influence and change the whole atmosphere in the room. The dancers may not be attuned to the creation, because they might be busy [thinking about] what they look like, what they’re saying.’ And I told Ohad, ‘That’s my job… I will be a bird. I’ll be another dancer from Batsheva. You’re not going to know I’m there.’ ”

Naharin sometimes appears like a benevolent father figure to his family of dancers. At other times he seems like a merciless slave-driver, pushing them past the point of exhaustion.

“He can be soft and rude and beautiful and ugly, and he can be someone you appreciate and like, and in a minute you really hate him and think, ‘How can you talk to your dancers [so badly] when they give their life to you?’ ” Heymann said. “But this is the guy, and the movie is keeping it.”

Naharin insists he has the dancers’ best interests at heart.

“I’m not abusing my power. I’m using the power of convincing to make my dancers realize that what I ask them is safe, what I ask them is going to help them discover new possibilities,” he said. “We have a trust that whatever I ask them, they know that it’s for the benefit of the moment, of dance, of the process, of the piece, and it’s something that makes them grow. So even if I’m very demanding, it’s for a reason.”

In the film, Naharin’s greatest triumph comes during the preparation for Israel’s 50th anniversary celebration in 1998. Batsheva was set to perform “Kyr” (“Wall”), in which male and female dancers strip down from suits to undershirts and boxer shorts while shouting the lyrics to the Passover song “Echad Mi Yodea” (“Who Knows One”).

Ultra-Orthodox Jewish leaders took offense, and the office of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pressured Naharin to have the dancers appear in long underwear. Instead, Naharin resigned and his dancers dropped out of the program in solidarity. The incident led to massive parades in support of Naharin’s stand against religious censorship, and he returned to the company’s helm as a national hero.

“Mr. Gaga” presents a portrait of a brilliant, if somewhat flawed, artist. Along the way, it also shows us moments of sublime beauty that can only be achieved when passionate dancers push themselves to their physical limits.

Batsheva performs “Decadance 2017,” a repertory program of the company’s celebrated works, at Segerstrom Center for the Arts in Costa Mesa on Feb. 8. “Mr. Gaga” opens in theaters in Los Angeles on Feb. 10.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.