As a young woman, my husband’s grandmother, Etel, or Babi as we called her, went off with her sister Iren from their tiny village in eastern Hungary to the big city of Budapest, where they had adventures and worked in a clothing factory, one as a seamstress, the other a shipper. Had they stayed in Budapest, they might have faced a different fate during the war. But less than a year after going, they returned home to Óféhérto, and on Passover, they were rounded up and sent to a ghetto in nearby Kisvárda. This was happening all over the Hungarian provinces. There were about 800,000 Jews in Hungary at the time; as Jonathan Freedland writes, “They were the last ones left, the one major Jewish community not yet to have been pulled into the inferno.” For the period of the Omer, when Jews count down the seven weeks from Passover to Shavuot, Babi and Iren-nenye, though they didn’t know it, were counting down their time in the ghetto. At the end of it, they were told they were being transported to a new location, a work camp.

The name “Auschwitz” meant nothing to them.

Why would it?

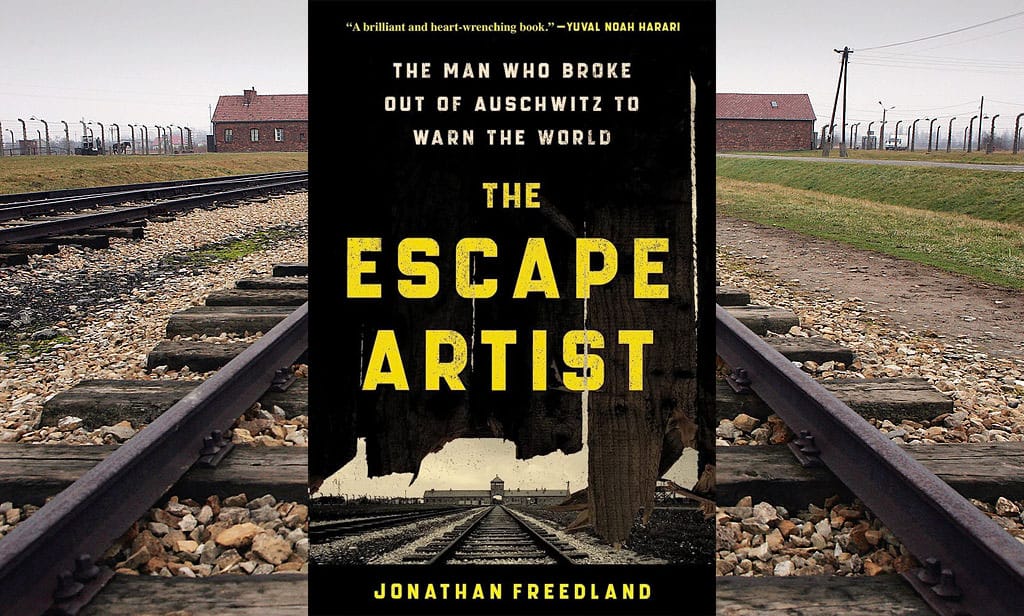

Reading Freedland’s new book, “The Escape Artist,” subtitled “The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World,” I can’t help but think how devastating it is that in April 1944 Babi and Iren-nenye—and other family members who did not survive—were ignorant of Auschwitz, the now notorious concentration and death camp where over a million Jews were slaughtered, most on arrival. Devastating—because they could have known about it. Known, and perhaps fought, or perhaps fled. After all, the very day that Babi and Iren-nenye arrived in Kisvárda, two Slovakian Jewish men, Walter Rosenberg and Fred Wetzler, did the impossible: They escaped Auschwitz. Their mission was to tell everyone exactly what Auschwitz meant and why it needed to be stopped.

“The Escape Artist” chronicles Rosenberg’s life, from his early days in Slovakia to his final days, like Babi and Iren-nenye, in Canada. His character—brilliant, paranoid, bad-tempered, charming—jumps off the page.

The vivid details of the escape by Rosenberg, who later became Rudolf Vrba (Freedland chooses to center him as the subject and hero of the book), and Wetzler make “The Escape Artist” read more as a thriller than a history textbook. Freedland, when not writing for the British newspaper “The Guardian”; doing his weekly podcast “Unholy” with Tel Aviv-based news anchor, Yonit Levi; or writing plays for the stage, is, under the pseudonym Sam Bourne, a thriller writer. Most chapters of “The Escape Artist” end with a cliff-hanger or a sense of ominous foreshadowing. Sometimes the impact of these closing lines rests on the knowledge of his readers. For example, when Rosenberg takes the opportunity to leave Majdanek, we read that “optimism entered his heart,” and Freedland adds, “Thank heavens he had rejected the advice that would have kept him in Majdanek and away from here. Because fortune really did seem to have smiled upon him” before adding the chapter’s concluding two-sentence paragraph: “It was 9 p.m. on 30 June 1942. And Walter Rosenberg was in Auschwitz.”

Rosenberg and Wetzler broke out of Auschwitz, an extraordinary feat. They made their way through the treacherous, enemy-filled landscape until they found the still-functioning Jewish council in Bratislava. They told their story and the story of Auschwitz in spare, unsentimental prose, and their report was replete with numbers, maps and names. It was translated into multiple languages and sent around the world. All this happened while Babi and Iren-nenye counted down the Omer.

So, what happened?

What happened was that the world didn’t listen. What happened was that the world didn’t care.

But there was one community that should have listened, cared, more than any other. Before the men broke out of Auschwitz, a German political prisoner told Rosenberg that Nazis were building a new railway line, direct to the crematoria, in preparation for the enormous influx of Hungarian Jews. His statement was confirmed by SS officers, who drunkenly revealed that they were hungry for some “Hungarian salami.” It would have been ideal if the information Rosenberg and Wetzler provided about Auschwitz caused the Allies to bomb the railroads or otherwise turn their attention to disrupting the deportations, but the immediate focus was on the immediate danger: Hungary.

Rosenberg and Wetzler understood this, as did the Slovakian Jewish council. And so, on April 28, the Vrba-Wetzler “Auschwitz Report” was handed to Rezsó Kasztner, the de facto leader of Hungarian Jewry.

What Kasztner did once he got hold of the Auschwitz Report is well known. Kasztner, deciding to save the few and risk the many, suppressed the information. The deportations began, and 437,402 Hungarian Jews, at a rate of 14,000-15,000 per day, were sent to Auschwitz; 90% of these men, women, and children were gassed on arrival. Babi and Iren-nenye were lucky; their sister, brothers, nephew, nieces and cousins were not.

The Auschwitz Report, however, did save lives. Although it is slightly misleading that “Rudolf Vrba and Fred Wetzler … saved 200,000 lives” as Freedland writes (a claim repeated on the back of the book), it is true that the report led to the cessation of deportations from Budapest at that time. Later on, unfortunately, more tragedy was to be had. In the autumn of 1944, the government was taken over by the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian party that was as hellbent on the mass extermination of Jews as the Nazis. Nonetheless, the rate of survival was higher in Budapest than anywhere else in the country, and more than 100,000 Jews were in the capital city upon liberation.

Nonetheless, the rate of survival was higher in Budapest than anywhere else in the country, and more than 100,000 Jews were in the capital city upon liberation.

There are many reasons that I think this book is essential reading. Remembering the heroes of the Holocaust, of which Rosenberg/Vrba and Wetzler are surely two, is important. But there’s more to it. Rosenberg’s unique overview of Auschwitz, his long period in the camp, and status and assortment of duties made him a key witness. No wonder he testified in the trials of Nazis and Holocaust deniers. Now that he’s gone and can’t testify himself, we need his story in his stead—and we can thank Jonathan Freedland, who conducted exhaustive research, including extensive interviews, for giving it to us.

In memory of Etel Gelbman Guttman (1919-2009) and Iren Gelbman Mandel (1921-2015).

Karen E. H. Skinazi, Ph.D, is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.