My big mistake, upon arriving at Jeffrey Katzenberg’s office, is that I didn’t bring my ballet slippers.

But no one really told me about the choreography of a visit here, in which Katzenberg’s vassals at DreamWorks Animation, the company he co-founded and oversees, welcomed me in, warmed me up and made me wait. It’s a very pretty dance, though, past the koi ponds and cobblestone drive, the sports cars and sprawling courtyards, and into the sleek reception area where a polite lady takes my name, suggests a seat and fibs a little, saying, “They’ll be down for you in a moment.”

After I’ve flipped through a trade or two and touched up my lip gloss, the publicity chief arrives to escort me to Katzenberg’s office. “You have one hour,” he reminds me — one short hour — in which to attempt to pin down the prolific executive. Which worries me. Katzenberg has been around too long to make the mistake of telling a reporter anything truly revealing, so the prospect of a probing interview seems both ambitious and unlikely. And yet, surely such a calculated man has his motives for talking to me today. Normally he is so wary of publicity that when the journalist Nicole LaPorte set out to write what would become a 477-page book on the DreamWorks story — “The Men Who Would Be King” — Katzenberg, along with partners Steven Spielberg and David Geffen, repeatedly refused to be interviewed. “Not a chance, not a chance,” LaPorte reported Katzenberg as saying.

One gets the impression that, in Katzenberg’s world, if he can’t be sole author of his story, he has no trouble trying to frustrate its telling. Don’t like it? There’s the door.

When I finally reach the realm of DreamWorks’ high priest (this warm-up has been sort of like the long trek to a Japanese Buddhist temple that prepares one’s soul for the moment of prayer), an assistant spots me coming down the line and jumps up to give Katzenberg the 30-second warning.

But four feet shy of Katzenberg’s door, the publicity chief suddenly balks and we literally pivot — two ungraceful ballerinas — to the side. “Listen,” he cautions, “if Jeffrey gets bored, he’ll probably try to wrap it up at around 45 minutes. So ask your best questions first.”

Was that a warning or a tip? No matter, a little flurry of butterflies begins beating their wings in my abdomen as Katzenberg traipses out of his office.

Dressed in a light-colored cashmere sweater and jeans, he whispers to one of his minions and faces me. Beneath rimless glasses, he has oval-shaped hazel eyes and wears a faint smile, giving him a kind of wistful, bedroom look. He is discernibly fit, the silhouette of muscular arms apparent even beneath his sweater, enhancing the tough-guy guise his diminutive frame otherwise denies him. It occurs to me that anyone who thinks of Katzenberg as small has never stood next to him. He has a colossal presence.

Disney’s “Beauty and the Beast.”

I quickly lay out my one-hour plan: his professional legacy, his family life, his political aims and philanthropic goals, his future dreams, his past regrets, his very (Jewish) soul. He’s cool with all of it. It is his life mantra, he tells me, “to exceed people’s expectations.”

“That goes to my philosophy about every thing,” he says, offering the secret to his success upfront: “I have one philosophy that I live by, which is: Whatever you do, give 110 percent of yourself — in anything you do that’s important to you. I try to do that as a husband and a father, whatever I take on. Anything. Including this interview.”

Katzenberg is sitting upright in his chair, and his gaze is unerringly direct; several times, I have to cajole myself into averting my eyes just so I can reference my notes. He is surprisingly soft-spoken and a little laconic; his cadence can be dry and slow, the calculated speech of someone used to being listened to. And talked about.

“I remember the first time I came to Los Angeles,” Katzenberg recalls. “I was probably 22, 23 years old. And I worked for an amazing man” — the independent producer and former CEO of United Artists, David Picker, who helped launch the James Bond franchise — “and I came out here and stayed at the Beverly Hills Hotel, and this was all like a fantasy come true.” His timing was providential; his visit fell a week before the Academy Awards. “I remember on my way back to the airport, you know, in the taxi, after having been exposed to all sorts of different things [that] week, I remember having this feeling like, ‘OK, so here’s what you gotta do in this town: You gotta win an Academy Award, and you’ve got to own a house on the beach in Malibu.’ ”

He laughs, hearing himself say this. “Those are the two things,” he says. “Those are the two ambitions.”

Nearly four decades later, Katzenberg has achieved a level of success in Hollywood that makes his early goals seem quaint. He has become a titan of the industry: a revered business leader, a studio founder, a devoted philanthropist, one of the nation’s top political fundraisers and a billionaire to boot. After so many years patiently laboring under the tyranny of other leaders (Barry Diller, Michael Eisner) or greater talents (Steven Spielberg) — “I was a great first lieutenant,” he admits — Katzenberg has finally cemented his role as the godfather of Hollywood. And now that he’s become a kind of industry father figure, his values as an American Jew are on full display: For Katzenberg, true glory is about having a heroic influence, both on the (infamously shallow) industry in which he works, and the world.

DreamWorks Animation’s “Shrek 2”

But the Malibu beach house had to come first. Sometime in his mid-30s, when the acquisition of Hollywood prestige depended as much on the appearance of success as on actual accomplishment, he purchased a strip of shore on the now-infamous, guarded “Billionaires’ Beach,” an über-exclusive section of Malibu’s Carbon Beach that Katzenberg claims he bought “long before you needed to be a billionaire.” It was just as well, since in order to join DreamWorks in 1994 with his one-third equal partnership, he was forced to mortgage his home, among other assets, to pony up the $33 million Spielberg and Geffen had burning holes in their pockets.

Winning an Oscar proved a greater challenge. Although his work as a film studio executive produced several award-winning movies — “Beauty and the Beast” and “The Lion King,” for example — he did not personally receive an Oscar until December of last year when he was awarded the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. “In many respects,” he says, “it’s kind of a better one, because it’s for things I did for other people rather than what I did for myself.”

Like many in Hollywood, Katzenberg’s early career schooled him in the art of being the underdog. He was Picker’s assistant at Paramount until then-Chairman Barry Diller took Katzenberg under his wing; within five years, he was promoted to vice president of production. There, however, he found himself a notch below a brash and fiery executive named Michael Eisner, with whom he began a notorious and tumultuous 19-year partnership. In that bond, Eisner was boss. So when Eisner was passed over as Diller’s successor, he left to become CEO at the Walt Disney Co., and Katzenberg, his ever-faithful deputy, followed.

For a while, Disney was good for Katzenberg. Beginning in 1984, he led the feature film department, which back then was last at the box office, behind all the other major studios. Within three years, Katzenberg had helped catapult Disney into the top spot at the box office. With a proven track record, he decided to take a risk the following year, releasing the half-animated, half-live-action movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.” Billed as a cartoon crime fantasy for grown-ups, it was rife with murder, mayhem, sex and scandal, and became a sensation, marking “the first time beloved animated characters from rival studios — such as Disney’s Mickey Mouse and Warner Bros.’ Bugs Bunny — appeared together,” the L.A. Times reported. “Roger Rabbit” became the second-highest-grossing film of the year, and by Katzenberg’s hand, “the golden age of animation” had begun. Katzenberg had found his niche.

In the wake of “Roger Rabbit” (1988), he revived Disney’s moribund franchise with a string of animated mega-hits: “The Little Mermaid” (1989), “Beauty and the Beast” (1991), “Aladdin” (1992) and the royal of them all, “The Lion King” (1994), which won a Golden Globe for best picture and remains the second-highest-grossing animation film of all time (right behind “Shrek 2,” which Katzenberg would later produce at DreamWorks).

Today, two decades later, Katzenberg’s list of credits remains impressive and evokes nostalgia for the days when Hollywood prized originality over repetition — a subject he knows well. In fact, it was in January 1991 that Katzenberg penned an explosive 28-page memo assailing Hollywood’s “blockbuster mentality” and calling for change. If success in the movie business once depended on “the ability to tell good stories well,” it was relying more and more on “big stars, special effects and name directors,” which he deemed wasteful. Entertainment, Katzenberg wrote, had become a “tidal wave of runaway costs and mindless competition,” producing products with a shelf life “somewhat shorter than a supermarket tomato.” It was time to return to creativity and risk-taking.

It sounds a lot like the “Jerry Maguire” story, I suggest.

“It was ‘Jerry Maguire,’ ” he says in a burst of excitement. “Cameron Crowe will tell you that,” he says, referring to the writer/director who conceived “Maguire” after reading the memo. “That is art imitating life.”

From left: Anti-Defamation League (ADL) Pacific Southwest Regional Director Amanda Susskind; ADL Regional Board Chair Seth M. Gerber; DreamWorks Animation CEO and 2013 ADL Entertainment Industry Award honoree Jeffrey Katzenberg; ADL National Director Abraham Foxman; and actress Sarah Chalke and actor/comedian Rob Riggle, who served as emcees, at the Anti-Defamation League Centennial Entertainment Industry Dinner on May 8.

Exactly two decades later, Los Angeles Times columnist Patrick Goldstein pointed to the memo as a turning point in the career of its author: “It’s clearly one of Katzenberg’s first efforts to transform himself from a dogged production executive best known for a punishing work ethic into an industry strategist and spokesman.”

Looking back, Katzenberg says Disney did him good, and he did good by Disney: “I could not have had a better run,” he says, “using whatever measure you want to use — talk about either great movies, great box office, great television shows, financial results …”

Katzenberg also helped facilitate Disney’s purchase of Harvey and Bob Weinstein’s Miramax Films in 1993, adding to his resume. According to Katzenberg, when he took over as chairman in 1984, Disney was losing $200 million a year and running an additional $2 million deficit in operating costs. “When I left, 10 years later, we were doing $10 billion in revenue and $850 million in operating profit.” Considering what happened in between, the feathers in his cap were a lifeline, because had Katzenberg’s record been any less distinguished, his feud with Eisner might have finished him for good.

But nobody gets as high up in Hollywood as Katzenberg without a little lurid lore rivering through his legacy. When Disney President Frank G. Wells, whom Katzenberg is fond of describing as his and Eisner’s “marriage counselor,” died suddenly in a 1994 helicopter crash, the brilliant, bold, melodramatic Eisner and his stubborn, dedicated deputy clashed hard. “The marriage just blew up,” Katzenberg said.

It was a dirty divorce. There were brawls and broken promises and distastefully low blows. Katzenberg was unceremoniously fired. During the lawsuit that followed — in which Katzenberg sought restitution to the tune of $250 million — it famously came out that Eisner had reportedly called him a “little midget,” an insult now too renowned to deep-six. New York Magazine’s Michael Wolff famously described their breakup as “so weird, so extreme, so on-the-sleeve, so futile and unnecessary and just not done.” The nebulous monolith that is Hollywood mostly sided with Katzenberg, aided and abetted by encouraging ads in Variety, the support and friendship of men named Spielberg and Geffen, and, Wolff noted, a timely “human relations” award from the American Jewish Committee that helped refocus Katzenberg’s image.

Given the marriage analogy, I ask Katzenberg if he still feels pain or loss. “Painful now?” he asks. “No.” And, at the time? “Not really,” he says dispassionately. Not even after 19 years of partnership? “I was just practical about it,” he explains, likening his experience to that of a jilted lover: “It was, you know, not what he wanted. He was done.

“And, you know,” Katzenberg continues, “it actually just freed me to get on with another chapter. It was painful leaving a place I had spent 10 years building, and a team of people I had worked hard to put together, who were kind of my extended family. So, yeah, that was hard. That was the emotional in it. But, you know, it pushed me out of the nest. In retrospect, it was a great thing.”

About six months after Wells died, Katzenberg left Disney. And not six months after that, DreamWorks was born. For someone who has dealt “in fables and allegories and metaphors” for a living, it was about as happy an ending as he could have hoped for, but, perhaps more importantly for Katzenberg, it was an ending.

“I thought I would be at Disney for the rest of my life,” he says. “And that I’d be with Michael. I always said, the day I left Disney I took the rearview mirror out of my car. And I never look back. And I didn’t, and I haven’t, and I’m not sure I ever will. It was a great time, and lots of wonderful things were accomplished. But I’m living in today, and for tomorrow.”

For a moment, he is silent.

“I’m not someone who … it’s just always hard for me to …” he says, stumbling through his thought. And as he speaks, it looks as if Katzenberg might finally let his guard down.

But in less than a minute, he recovers himself and re-armors: “The past just doesn’t interest me that much, to be honest with you.”

The Motion Picture & Television Fund, chaired by Jeffrey Katzenberg, manages the Wasserman Campus in Woodland Hills, which features the Katzenberg Pavilions.

Ready to Take a Gamble

Katzenberg grew up in Manhattan, the son of an artist mother and a stockbroker father. By the time he was 14, he was volunteering for John Lindsay’s successful mayoral campaign. Even as a kid, “I was entrepreneurial, always looking to do things, organize things, you know, when there was a snowstorm, we’d go shovel sidewalks for storeowners on Madison Avenue, and we’d have our lemonade stands and all those things that kids do.” Katzenberg says his mother encouraged him to pursue his passions. “I didn’t like boundaries, and she was pretty good about letting me explore the things that excited me.” And his father? “My dad put the gambler in me,” he says: “Sport, competition, gambling was just a part of everyday life. [My father] was a stockbroker, incredible card player, incredible tennis player, great backgammon player. He was always involved in hustle. Hustle and play and gamble. And he was very good at it, and he sort of taught me that.”

Judaism also played a role, albeit a peripheral one. “I wasn’t bar mitzvahed, but on the other hand, faith was in our life. I went to Sunday school; we belonged to Emanu-El,” he says, referring to the historic Reform synagogue on Fifth Avenue and East 65th Street. “I would say it was a part of our culture.”

Given that his Jewish upbringing wasn’t religiously immersive, I ask Katzenberg what his Jewish identity has accorded him in life. He thinks for a minute, then says, “Pride. Conviction. A sense of belonging. The Jewish community of New York is one in which there is a lot of connection. Much more connected [than in Los Angeles]. You’re a part of something there. [In Jewish life] there’s a connection to your roots and to Israel, a sense of belonging and a sense of obligation.”

Rabbi Marvin Hier, dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, can speak to Katzenberg’s Jewish life, if not religiously, then in terms of his commitment to the community: “If you know Jeffrey, you know that Jeffrey doesn’t like long telephone conversations,” Hier says sardonically. “Sometimes Jeffrey can speak for 30 seconds, but to me, he is the epitome of the talmudic dictum in Pirkei Avot that says, “Emor me’at — say little, v’asey harbeh —– but do much. That fits him to the T. You ask him to do something — he says, ‘Yes’; you have about a 30-second conversation, but when you come to the delivery, it’s amazing.”

Over the years, Katzenberg has not only helped fundraise for the Wiesenthal Center, attending its annual banquets and inviting his friends, he has also helped secure celebrity narrators, such as Sandra Bullock to voice Golda Meir, for the center’s award-winning documentaries. Hier also said that it was Katzenberg — along with Universal Studios chief Ron Meyer — who advised him to create an in-house production company, Moriah Films, instead of outsourcing the center’s film work.

Katzenberg clearly takes his role as community leader seriously, most evident in his commitment to philanthropy. His business success has, of course, made him vastly wealthy — “He’s the world’s greatest salesman,” one longtime observer put it. In 2005, Forbes estimated Katzenberg’s fortune at somewhere between $850 million and $1 billion, and when it comes to giving it away, Katzenberg deploys skill and strategy. He and his wife, Marilyn, are committed to a number of causes, most notably the Motion Picture & Television Fund (MPTF); Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; and USC and Boston University, the alma maters of their twin children, David and Laura, now 30.

“We have a very simple philosophy,” Katzenberg says, explaining that they give to institutions and organizations that have most intimately touched their lives — the hospitals where their children were born, the schools where they were educated, and to the social service organization that supports tradesmen in the industry Katzenberg feels he owes so much. “Every dollar I’ve made in my career has been in this industry, and I have a very strong socialist point of view about society” — something he attributes to his parents’ tutelage — “which is, the people who are rich and successful need to take care of the people who are not.”

The Katzenbergs, married for 38 years, created a private family foundation through which they donate around $1 million and sometimes much more each year. Recently, they gave $1.25 million to Boston University; they also made two other major gifts, in amounts they would not disclose, to the Katzenberg Center for Animation at USC and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Additionally, they contribute about $25,000 to each of the many charity dinners they attend each year — including ones for the annual Simon Wiesenthal Center, which Katzenberg frequently chairs, Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation and the Anti-Defamation League.

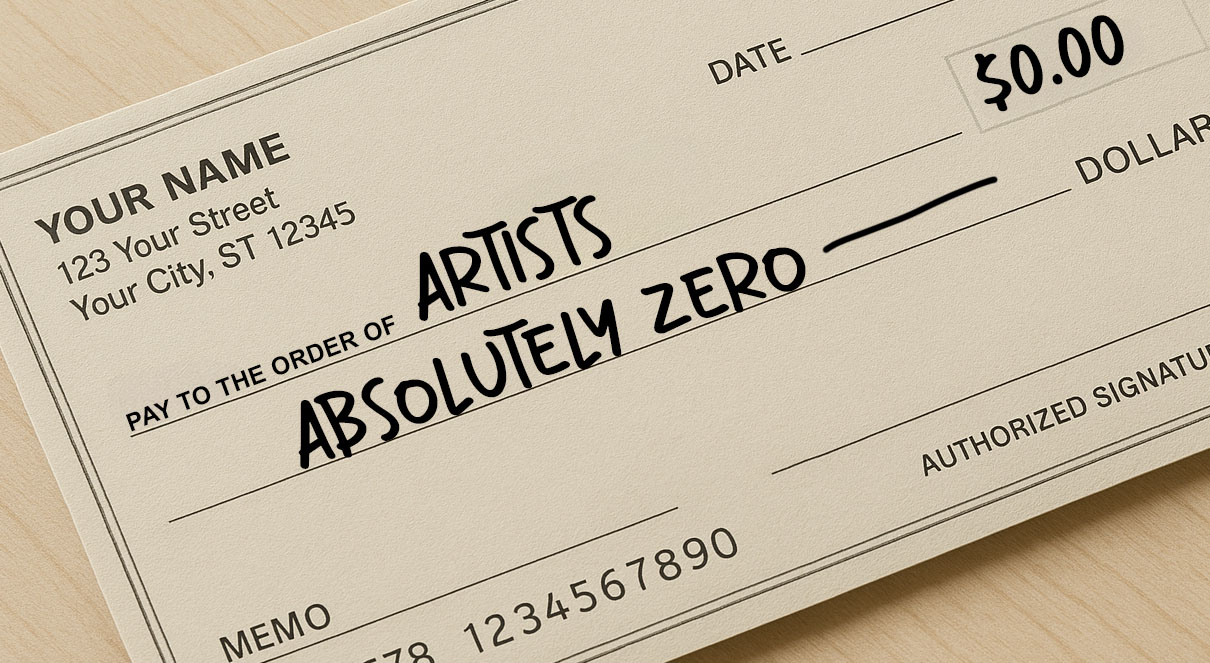

But far and away, Katzenberg’s foremost philanthropic passion is serving as chairman of the board for the MPTF, which he has done for nearly two decades. MPTF manages the Wasserman Campus in Woodland Hills, best known as the Motion Picture home, a sprawling retirement facility for industry veterans, along with six outpatient health care centers that together service an estimated 60,000 patients. In January 2012, Katzenberg and George Clooney announced a $350 million capital campaign to support the future of the fund, to which Katzenberg, Spielberg and Geffen each made gifts of $30 million, helping Katzenberg bring the fundraising total, thus far, to $250 million. “The movie and television business have given me extraordinary wealth,” Katzenberg says, “so in the very industry which has given so much to us, it is, to me, the first and most important place to give back.”

In 2010, however, Katzenberg found himself in the hot seat when MPTF was facing a budget shortfall of nearly $10 million per year. The financial reality that threatened to bankrupt the fund prompted a controversial decision to shutter its long-term care facility and hospital, which served the home’s most infirm residents. Adding insult to injury, mismanagement of the crisis led to a nasty public imbroglio (the subject of a 2010 Jewish Journal cover story) that pitted some of the vulnerable residents against wealthy Hollywood donors in a prolonged battle that has only recently been resolved. When I bring up that whole mess, Katzenberg becomes heated — and for the only time during our interview, he goes off the record. When his diatribe finally reaches its denouement, he says, “Anybody else would have walked away from this.”

So why didn’t he?

“Because I don’t give up. Show me a good loser, and I’ll show you a loser. I was never going to give up. I wasn’t going to give up on the people. You know, Lew Wasserman put this in my hands on a very personal level. He said, ‘This is your responsibility now.’ ”

Wasserman, the legendary studio executive and talent agent who, for a time, was considered the most powerful man in Hollywood, is clearly a role model for Katzenberg. Known by insiders as “The Last Mogul,” as a biography of the former chair and chief executive of the Music Corp. of America is titled, Wasserman famously cultivated relationships with rising politicians (he was an early supporter of then-Gov. Bill Clinton), unabashedly demanded support for Israel and united the entertainment community in support of causes he believed in.

No Hollywood titan since has been able to fill the vacuum Wasserman left behind when he died in 2002 — until, some say, Jeffrey Katzenberg.

According to a recent article by Andy Kroll in Mother Jones, Katzenberg is currently the nation’s most powerful and effective Democratic fundraiser. Since 1999, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, the Katzenbergs have donated an estimated $4.8 million to Democratic causes, topping every other star political donor in the United States — including George Soros and the right-leaning Koch brothers — except for Sheldon Adelson ($94.2 million).

Kroll portrayed Katzenberg — who did not consent to be interviewed — as a “deep pocketed kingmaker” much cherished by the Obama administration for his fundraising efficiency and low-maintenance personality. When he and George Clooney hosted a final-stretch campaign fundraiser for the president last spring, it became the highest-grossing campaign dinner in history, raising $15 million in one night. Katzenberg’s strategy for getting wealthy democrats to pony up their pocketbooks was simple: Show them a good time. He reportedly “fussed” over details like seating arrangements — leaving an extra seat at each table so Obama could “mingle” (something the president is oft criticized for doing poorly) —– which prompted Kroll’s winning description of the dinner as “a night of political speed dating.”

Another of Katzenberg’s tricks is his old-fashioned etiquette. In the age of mass e-mails and Facebook posts, Katzenberg is old school, plying his friends with “personal calls and handwritten thank-you notes.” Jim Messina, Obama’s campaign manager, described him to Kroll as “one of the best, if not the best, fundraisers out there,” and, according to the same piece, he doesn’t ask for much in return: “No ambassadorship to Switzerland, no regulatory tweak, no nights in the Lincoln Bedroom,” Kroll wrote. Although, he added, there are some perks: “Obama takes Katzenberg’s calls, and he and his political adviser, Andy Spahn, visited the White House almost 50 times between them during Obama’s first term.” Not to mention, “It has also left [Katzenberg] well positioned to advocate for his industry’s and his company’s interests in China’s booming film market.”

Katzenberg Pavilions

East Meets West

In 2012, Katzenberg launched a major joint venture with a group of Chinese investors. Dubbed Oriental DreamWorks, it is a China-based Disneyesque company that plans to produce original Chinese movies, as well as theme parks, games and other products.

Katzenberg, however, is adamant that he has not, and will not, call in any political favors on behalf of his business interests. “Frankly, that complicates things, it doesn’t help things,” he says. But in April 2012, the story broke that the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was investigating DreamWorks Animation, along with 20th Century Fox and the Walt Disney Co., alleging they had bribed Chinese officials “to gain the right to film and show movies there.” Katzenberg says the accusation is outrageous and admits that although he’s heard the news reports, he insists, “There has never been an SEC investigation of us. I’m telling you, no one has ever asked us for anything with regard to an investigation of us in China; nobody has asked for documents, nobody has subpoenaed us. I don’t know what they’re talking about.” (A spokesperson from the SEC would neither confirm nor deny an ongoing investigation.)

What we do know, however, is that commerce between the two countries, and especially between the two entertainment industries, has required political maneuvering. In fact, also in 2012, Joe Biden personally intervened to end a three-year trade dispute between China and the Motion Picture Association of America, which had been lobbying unsuccessfully to increase film quotas for American-made movies in China, as well as to increase Hollywood’s percentage of the box office gross. Katzenberg happened to be with Biden and then-vice president of China, Xi Jinping, now the president, in February 2012 when a winning deal was made during Xi’s visit to Los Angeles. “That had nothing to do with me,” Katzenberg insists. “I happened to be standing in a corridor when he was making this deal, and [Biden] asked me, you know, what was my opinion.”

Nevertheless, Katzenberg has a lot riding on the U.S. relationship with the Chinese. If DreamWorks Animation has any hope of becoming like Disney, much depends on the success of this investment — and Katzenberg has been doing his part to see it through, having traveled to China at least once a month for the past two years. His business bible, he tells me, is Henry Kissinger’s “On China.” “I literally read it twice. It’s brilliant,” he says.

“Ten years from now, China will be the center of the universe,” Katzenberg declares. “And that’s what’s exciting — climbing mountains.”

What drives him now isn’t fame or fortune, he says. “It’s not about the money — it was never about the money.”

His goal is simpler: “New mountain. New challenge.”

Two minutes before the end of our hour, I realize I’ve forgotten to ask Katzenberg about Israel. He tells me he has personally taken Jerry Seinfeld, Ben Stiller and Chris Rock on visits there, which I hadn’t known. “I think it’s important,” he says. Israel “is a jewel. It’s this amazing beautiful gem that exists in a place where there are not a lot of gems.”

So, in addition to the business, philanthropy and politics, Katzenberg quietly supports Israel and even leads trips there. It is all so very Lew Wasserman. The Wiesenthal’s Rabbi Hier even compares Katzenberg to the unnamed heroes of the Bible, the characters who never starred in the Jewish story, but who nevertheless made an impact on the whole of Jewish destiny.

“If you want to know who’s going to change the course of Jewish history, you don’t necessarily find them in the temple on Shabbos getting an aliyah,” Hier says.

Hier acknowledges the skepticism with which more observant Jews might view the likes of Katzenberg, who rarely steps into a synagogue. “When I was in yeshiva, I thought everyone there who wears a yarmulke is the epitome of all goodness, but it’s often people not involved religiously who do more work for the Jewish people than some who wear yarmulkes.”

“Who’s gonna say Theodor Herzl didn’t work for the Jewish people because he didn’t wear a yarmulke?” Hier says wryly. “You might not see some of these people on Shabbos, but what they do affects everybody.”

At 60 minutes on the dot, my time with Katzenberg is up. The PR chief peeks his head in with an interested expression. “How’d it go?” he mutters.

Katzenberg answers: “Very lively.” Done.