“I’m not a new world girl,” said artist Lea Shabat, sitting in her home studio in Montreal. “What can I get you?” she asked. “A coffee? Some tea?” She laughed and lamented that she could not offer me something to drink, given that I was in her home only by way of a computer screen. Perhaps there is always something mildly inauthentic about encounters that transpire by way of technology, but for me, getting to know Shabat and see some of her private work was a delight, even if we were nearly 4,000 miles apart.

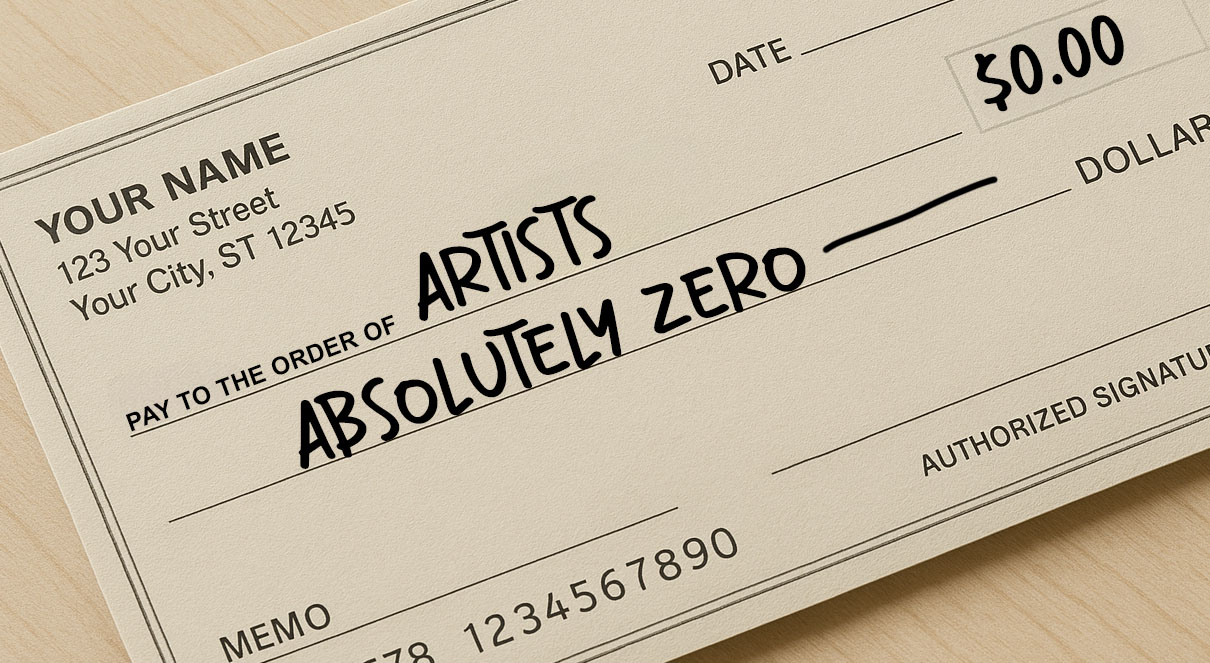

Shabat is a rare jewel in the world of art and painting — certainly not undiscovered but also not as commonly known as one would expect when looking at her paintings. When I discovered her work last year, I wondered how it was possible I hadn’t come across it before. Perhaps it’s because Shabat, who says she is from “the old generation,” sees her art not as a commodity but as an extension of herself. “I don’t want to part [with my paintings],” she said. “It’s hard to let go of your children. I like to show my work, but I don’t want to think about the moment I have to part with it.”

Shabat was born in Casablanca in 1945 and left to France with her family for two years when she was young. From France, the family went to Israel aboard an immigration ship in 1950. In Israel, she and her family lived for a time in tents in one of the many ma’abarot (transition camps). I suspect her intense love for nature was nourished in this way, as she lived virtually as one with nature, without the confines (or conveniences) of building and structure.

“In Israel, I did my primary school, and we lived in tents,” she said, “and it was a beautiful life of nature … I was a little girl, and the Jewish community was very embracing. I also learned about different cultures like Yemenite and Russian.”

Shabat’s early exposure to transnational travel and to people from different cultures was a touchstone to the artistic journey on which she would one day embark. “But then I grew up,” she said, “and I went to secondary school, which was an agricultural school, so I had the experience of riding on a platform, you know, a pulled tractor with horses and sometimes camels … I love nature.”

She started painting at the age of five, and by the time she was an adult she longed to attend art school, but it was not part of her path. Instead, she had an arranged marriage to a man from Haifa. When she was in her mid-20s she moved with him to Montreal, “for love,” she said. They arrived alone in Montreal in the dead of winter, and she has resided there ever since. It’s a city that has been good to Shabat, who gave birth to two children there in addition to setting up her home art studio. “I’m not a party-goer,” she said. “If you see my backyard, it’s only trees, and I live with big windows and the sun shines on my face in the morning and at night, and I have no curtains. At night, I have the moon that comes and I’m really connected to nature. You can be one with nature, even in your home.”

But Shabat has always had an internal drive to be and feel free and unfettered. The idea of liberation is one she has explored not only in her work but also in her life. She has traveled all over the world and has lived in places like Cambodia and Indonesia and even Jordan, where she rented a little cabin in which to paint, for extended periods.

In Jordan, “I met the animals that I love,” she said. One of the first things I noticed about some of Shabat’s work is the prevalence of birds and other animals. In many cases they are, unsurprisingly once you know Shabat, moving and migrating; they are always in motion. In one piece — a triptych called “Mother Earth” — we see Shabat’s concern not just for animals but also for the world that sustains and nourishes them. In the top third of the triptych we see a woman’s body shaded in red with her arms raised above her with hands meeting above her head. From her breasts grow vines that work their way up to the surface of the mountainous ground, but it becomes heavier underneath.

“The turtle, the fish, the sea and the animals” are there, “and she’s feeding everyone from her belly … and the sea level is going down. We are losing a lot of nature … she’s feeding every form of animal,” Shabat said, looking at her painting. But “although the sea level is going down and we are losing a lot of nature, there is still hope.” She gestured to the top of the painting. “You see at the top, there are some sperm … [but] the earth is burning because the heat is on.” But though the sea is rising and the earth is burning, “she’s feeding everyone and everything, and she’s being depleted because she is not being nourished.”

I couldn’t help but wonder if Shabat sees some of herself in that figure, if she finds the endless job of women — to nurture and nourish others while pushing our own needs and desires from the forefront — as part of what drives her to paint in this way.

In “Out of the Rubble,” the figure of a person breaks out of a pile of colored bricks; white birds fly behind her as the person looks off into the distance. I asked Shabat about the birds and she was surprised by the question. “I don’t see birds,” she said. “I see liberation, being liberated from the traditional way.”

I couldn’t help but ask Shabat: What do you want to be free from? “Myself,” she said. “All I wanted to do is paint and read books and work in nature. And I raised my children on these principles. And I had a very nice partner who was a good man, but I wanted to go, you see?”

Shabat may long to be free, but in that longing for freedom she also finds a deep and intense love for children. It’s impossible to miss the shapes and forms of children throughout her work, usually appearing faceless. “They are present all the time,” she said, “the children in my paintings.” It seems like a bit of a paradox at first, to paint persistently of liberation, but then focus simultaneously on the presence of children. It isn’t that she paints them to point out that they are a burden; it’s the opposite. “It’s love,” she said, “and they are very intriguing. Children have their own mind, and that’s how I live.”

Shabat may long to be free, but in that longing for freedom she also finds a deep and intense love for children. It’s impossible to miss the shapes and forms of children throughout her work, usually appearing faceless. “They are present all the time,” she said, “the children in my paintings.” It seems like a bit of a paradox at first, to paint persistently of liberation, but then focus simultaneously on the presence of children. It isn’t that she paints them to point out that they are a burden; it’s the opposite. “It’s love,” she said, “and they are very intriguing. Children have their own mind, and that’s how I live.”

When Shabat traveled to Cambodia, a friend told her there was a hospital for children. “I jumped on it,” said Shabat, “I said, give me a room there, and I will teach.” There were 50 children there, all struggling with their health, and Shabat did art with them and taught them to paint. “The kids and my life are entangled,” she reflected. She has also worked with children with special needs, and so it’s not surprising that children appear in her work, even if sometimes only faintly, again and again.

Shabat’s personal and artistic emphasis on nature and love for children is the same ethos that guided her when raising her own children. Her daughter Stephanie is a prominent figure in the art world who credits her upbringing as the reason she decided to enter the profession. In honor of Shabat’s recent 80th birthday, Stephanie created an Instagram page to showcase her work. Shabat’s son, Eric, works in human rights and environmental peacebuilding. One might say that her children embody Shabat’s most treasured ideals, and that their work is an extension of hers. Perhaps this too is the hope Shabat imagines in her triptych “Mother Earth.”

Shabat has many memories of her own childhood, and some of these stories inform her work. When she was a child, she would walk three to five times a week with her father to the water where they would eat sandwiches and catch fish together. But one day, he had his bike and his fishing rod and Shabat knew he was leaving without her and was distressed.

“’Today, you’re not coming with me,’ he said. And I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because I will meet my friends there and my neighbors.’ He didn’t want me to be in company of adults. And I started to cry. So he went with his bike, and I was walking behind him and crying, ‘Take me! Take me!’ I remember this because I keep telling the story.” As Shabat got closer to her father on the bike, the hook from the fishing rod cut her neck, but her father did not realize. “I was crying. And he was looking away because he was on his bike, and he said, ‘Go home.’ But I kept running after him. Then the hook cut my leg, and he didn’t understand. I yelled, ‘Papa, look what happened to me.’ I went home and I took it out by myself. The fishing hook, you know, is for the fish not to run away.”

“’Today, you’re not coming with me,’ he said. And I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because I will meet my friends there and my neighbors.’ He didn’t want me to be in company of adults. And I started to cry. So he went with his bike, and I was walking behind him and crying, ‘Take me! Take me!’ I remember this because I keep telling the story.” As Shabat got closer to her father on the bike, the hook from the fishing rod cut her neck, but her father did not realize. “I was crying. And he was looking away because he was on his bike, and he said, ‘Go home.’ But I kept running after him. Then the hook cut my leg, and he didn’t understand. I yelled, ‘Papa, look what happened to me.’ I went home and I took it out by myself. The fishing hook, you know, is for the fish not to run away.”

The irony of being caught — with a fish hook — by someone who is trying to escape you is not lost on Shabat, who chuckles as she tells the story. But I can tell that it is a deeply significant story for her. And I wonder if, in all the faceless children scattered throughout her work, one of them is her, longing to catch up with her father, to not be left behind even as the adult version of Lea Shabat runs the opposite direction, forever chasing liberation.

At the end of our talk, I asked her if being Jewish influences her art in any way. “Not at all,” she said. But I couldn’t help but smile because it’s easy to see the theme of tikkun olam in her work. Pushing a bit, I asked, “Did you grow up religious at all?” Her answer may be one of the best lines I’ve ever taken from an interview: “Religious, no. Shabbat, yes.”

Monica Osborne is a former professor of literature, critical theory, and Jewish studies. She is Editor at Large at The Jewish Journal and is author of “The Midrashic Impulse.” X @DrMonicaOsborne