Library of Congress, via PBS

Library of Congress, via PBS As a producer with Ken Burns’ production company, Florentine Films, Sarah Botstein is one of the three director-producers of the new PBS documentary “The U.S. and the Holocaust,” along with Burns and Lynn Novick. The three have collaborated together since 2001, when they produced the ten-part miniseries “Jazz” on PBS. Botstein, Burns and Novick are to documentaries what “Magic” Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Pat Riley of “Showtime”-era Lakers were to the NBA — the gold standard.

Since “The U.S. and the Holocaust” began production in 2015, Botstein has had a special connection to the content of what would become an acclaimed three-part miniseries.

Long before the team started work on the series, and decades before Botstein started working at Florentine Films, the history of the United States in relation to the Holocaust was an ever-present force in her formative years.

Botstein’s paternal grandparents were Jews living in Eastern Europe during the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Her paternal grandmother Anne (born Ania Wyszewianska) came from an upper middle class Jewish family along the Russia-Poland border. She relocated to Switzerland while training in pediatrics. Anne also had an older brother named Leon who was one of the organizers of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in 1943. Leon would tragically be murdered during the uprising. On the other side of that family, Botstein’s great-grandfather’s sister committed suicide when her children were taken away from her to a death camp.

Botstein’s paternal grandfather Charles was born to a poor family in Odessa, Ukraine. Charles served in the medical corps in the Polish Army during the mid-1930s. He and Anne met while in medical school in Zurich and married in 1935. Together, as World War II began to consume Europe, the two would obtain refugee status in neutral Switzerland, but as foreign Jews, they couldn’t obtain Swiss citizenship. Between the rise of Hitler and the end of World War II, it took Botstein’s grandparents Anne and Charles 14 years to immigrate to the United States. They first filed paperwork in 1935 and were continually told that America’s quotas were full until they were finally admitted in 1949, through assistance from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. Even as accomplished doctors, immigrating to the U.S. was a daunting task.

Anne and Charles would go on to have three children, one of which was named after Anne’s late brother Leon.

In the U.S., Leon Botstein would become a revered symphonic conductor. And since 1975, he has served as president of Bard College in New York’s Hudson Valley. With his first wife Jill, they would have two children, Sarah and Abby. Leon’s musical prowess still influences Sarah, as she takes an active role in the music direction in all of the Florentine Films projects she’s worked on.

Sarah, the elder child of Leon and Jill, recalled special memories while growing up with her father’s parents nearby.

“I was extremely close to my father’s parents; they were like a second set of parents to me,” Botstein told the Journal. “They lived in the Bronx when I was a child. My father was very close and attached to them and he would stop by and see them on our way in and out of the city and on vacations. I often stayed with them. And then my parents divorced in 1979, and my sister [Abby] was killed tragically in a car accident in 1981. After that, I spent even more time with both my grandparents. So they were a very, very active influence on my young life. And then I went to Barnard, and in my senior year in college, my grandfather got quite sick and died. And my aunt and I spent a huge amount of time taking care of him in his last few months of life.”

In “The U.S. and The Holocaust,” family photographs of Botstein’s grandparents as young children are woven into the documentary (but not identified).

“There are some of our family photographs in the series, we [the filmmakers] all decided that if we’re going to find archives of communities around the world and they’re related to some of us, that’s sort of special for those of us who worked on the film. You don’t know who’s in the images. So there are three images of my family in the final cut of the series, and one of them is a picture of my grandmother’s family — she’s a baby in the image.”

Botstein reflected on how the shortened lives of her great uncle Leon and great-great aunt and her children affected her mindset while directing and producing “The U.S. and the Holocaust.”

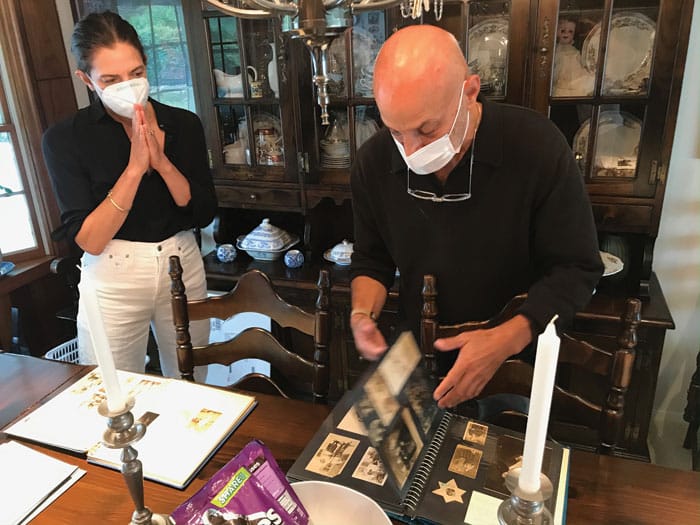

Sarah Botstein and interviewee Daniel Mendelsohn look through family photos.

“Both of those, to me, being a part of the uprising and then taking your own life, and your children having just been sent to their death — are very interesting ways to think about agency, how young Jews thought about what was happening,” Botstein said. “It’s similar for me — one of the more moving scenes in the film, which is one of the last scenes we edited, is the Warsaw uprising scene, because we learned about the Ringelblum Archives while we were recording narration. And that’s the incredible material that the Jews in the [Warsaw] Ghetto buried in these milk cans so that they would be remembered. We have a scene in the film about it. And tied to that in terms of my family, my great-uncle, whom I never knew, but was a legend because he is who my father is named after. And he stood up against the Nazis in just a remarkable way. And then my great-aunt I never knew, and her children — to think about that and why they made the choices they made.”

Though they were refugees greatly affected and displaced by the Holocaust, Botstein’s paternal grandparents were very much aware of how close they were to being victims.

“They never thought of themselves as victims, but as profoundly lucky to have made it [to the U.S.] and to have created as optimistic a future as they could for their children and their grandchildren,” Botstein said. “They’re not survivors in the traditional sense. They’re witnesses to history.” She emphasizes that when presenting history, you have to be very careful with the terms “survivor,” “victim,” and “witness” when describing who got out and why. Her grandparents had friends and extended family who were all three.

“I don’t actually remember a time where I wasn’t surrounded by lots of older Jewish people, some of whom had recently come to America, some of whom had direct relationships to the ghettos, the concentration camps, hiding, survival…” – Sarah Botstein

“I don’t actually remember a time where I wasn’t surrounded by lots of older Jewish people, some of whom had recently come to America, some of whom had direct relationships to the ghettos, the concentration camps, hiding, survival and others who like my father and my grandparents (who were both in medical school in Switzerland during the war) helping to save the relatives that they could and try to get papers,” Botstein said.

Botstein remembers her grandparents as incredible characters who hosted fun and hilarious family dinners. They spoke a combination of Polish, Russian and German — their descendants would call it “Botschtein-ese.” Her grandfather Charles was a “hilarious, larger than life character.” When he passed away at age 83 in 1994, The New York Times described him as “a pioneer in the use of radiotherapy in the treatment of uterine cancer.” Botstein’s grandmother Anne went deaf in her forties but continued practicing medicine. She even sewed a pillow for her granddaughter Sarah on nearly every birthday.

It comes as no surprise that, before becoming a part of one of the most respected documentary teams in television today, Botstein was exposed to powerful historical documentaries and books in her teens.

It comes as no surprise that, before becoming a member of one of the most respected documentary teams in television today, Botstein was exposed to powerful historical documentaries and books in her teens. In particular, she remembers when her father rented the 1985 French nine-hour documentary “Shoah” by Claude Lanzmann that features no archival footage.

“I really remember how profoundly that film affected him and why it was important for him to talk to me about it,” Botstein said. “I definitely remember reading Anne Frank, I remember my father in particular giving me books by Isaac Bashevis Singer — Jewish writers and thinkers, and hearing names — my father knew Hannah Arendt.”

“I really remember how profoundly that film affected him and why it was important for him to talk to me about it,” Botstein said. “I definitely remember reading Anne Frank, I remember my father in particular giving me books by Isaac Bashevis Singer — Jewish writers and thinkers, and hearing names — my father knew Hannah Arendt.”

At Columbia University-Barnard College in New York, Botstein majored in American Studies. While there, she became fascinated in how postwar generations were thinking about American Jewish identity, not through history so much as through literature. She wrote about Saul Bellow’s “Seize the Day” and Philip Roth’s “Goodbye, Columbus.”

After college, Botstein wasn’t quite sure what she wanted to do for a career, so she took a job as an account assistant at a public relations firm that had General Motors as a client. It just so happened that General Motors was then one of the primary underwriters for Ken Burns’ PBS documentaries dating back to 1984 with “The Shakers: Hands to Work, Hearts to God.”

She was nine when Burns’ first PBS documentary, “Brooklyn Bridge,” was released in 1981. When “The Civil War” was released in 1990, Botstein remembers everyone in her family and her college watching it.

And then while working for the PR firm representing one of Burns’ primary underwriters, Botstein jumped at the chance to meet him.

“I met Ken and I thought he was just charming and brilliant,” Botstein said. “And I remember ‘The Civil War’ coming out. I was in college and at that point, there was so much written about the use of still photographs to communicate moving images in film. And that was very interesting to me. I thought [Burns] was terrific. I loved whenever he had a film come out.”

While working in the PR firm, Botstein was dabbling in photography, and credits her stepfather Douglas Baz, a photographer, as an influence. Combining that with what she describes as “a visual way of thinking about history,” Botstein eagerly took advantage of the opportunity to join Burns’ team.

While working in the PR firm, Botstein was dabbling in photography, and credits her stepfather Douglas Baz, a photographer, as an influence. Combining that with what she describes as “a visual way of thinking about history,” Botstein eagerly took advantage of the opportunity to join Burns’ team.

“He was working on the ‘Jazz’ film, and they had one associate producer seat to fill, and he described the job to me as being ‘his wing man,’” Botstein said. “And I remember calling my parents and saying I’ve got this opportunity. I was living in New York at the time, and they said, ‘Don’t hesitate. Say yes. Unbelievable opportunity.’ I packed up my Jeep and went to this teeny tiny town in New Hampshire. My friends thought I was totally nuts. I didn’t know anybody. It was a total blizzard. I remember getting there, and the first day in the editing room — it was the first day we were editing ‘Jazz.’” The ten-episode, 19-hour miniseries premiered in January 2001 to rave reviews. And Botstein knew she had landed in the right career path.

“Being in the editing room is really an exceptional experience,” Botstein said. “It’s a very open, very collaborative, very intense, very brilliant place to be. And I thought, ‘I am so lucky. How did I ever end up here? I don’t know enough about film to have anything to contribute.’”

During the production of “Jazz,” the Florentine Films production team was still cutting on actual film rather than digital. Botstein had to fine-tune her talents at splicing pieces of film together to tell a story. She did research on the art and motifs of disco. She recalls a steep learning curve to become immersed in the history and catalogs of jazz pioneers Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn and Billie Holiday.

“After ‘Jazz,’ Ken and Lynn [Novick] sat down, and I sort of got hitched to Lynn’s films and worked on ‘The War’ with her,” Botstein said. Over the next 20 years, they would collaborate on “Prohibition,” “Vietnam,” “College Behind Bars” and “Hemingway.”

“College Behind Bars” has a special significance to Botstein, as her husband Max Kenner is the founder of the documentary’s focus: The Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). Kenner founded the BPI as a way to enroll “incarcerated women and men in academic programs that culminate in degrees from Bard College.”

“I have an extraordinary husband,” Botstein said. “Hearing about what he does and being around him is a great joy of my life.” They have two children, ages 11 and five.

Now with her own family, it’s not lost on Botstein for a moment how present-day antisemitism, xenophobia and hatred are a scourge in the U.S. that needs to be called out. “The U.S. and the Holocaust” was originally intended to be released in 2023, but the contentious climate led the filmmakers to release the series this fall.

“Ken really deserves all the credit for that decision,” Botstein said. “I think he was watching what was happening in the world and thought, ‘the sooner this film gets out for our country’s conversation, the better.’”

Burns spoke with the Journal about the urgency to release the film as soon as possible.

“We had a conversation with the head of the ADL, who reported that the level of antisemitic acts are at the level of the 1930s in the United States,” Burns told the Journal. “There is an urgency to almost every aspect of it.”

The team collapsed what normally would take them a year into six months so that “The U.S. and the Holocaust” could be released as soon as possible.

In the pre-pandemic years, Botstein and the Florentine Films team collaborated while sitting in a horseshoe shaped alignment of edit bays and research desks at the Walpole, New Hampshire studio. They have music stands with scripts, and work with pencils and different colored pens and lots of sticky notes. Botstein calls it a “fairly old-fashioned way” for a tiny group to put their heads together. But even when collaborating via Zoom during the pandemic, they made it work. Botstein said that the entire team “just brought their A-game” in a slightly different way than they would normally do.

“Ken and I often talk about this, and Geoff [Geoffrey Ward, lead writer of Burns’ films since 1984] too, treading over the same period in history over and over again through a slightly different lens is really interesting,” Botstein said. “In so many of our films, we’re looking at the ‘20s, the ‘30s and the ‘40s. We’ve done a film on Hemingway, we’ve done a film on Prohibition, we’ve done a film on the Second World War, and here we are again thinking about this period of time. Completely different lens.”

The Journal asked Botstein about the rise in antisemitism in the U.S. today, and in particular, this month—with the release of the “The U.S. and the Holocaust” coinciding with a spike in headlines around antisemitism.

”These are dangerous times and we need to be vigilant. Our film is just one reminder of how precious American democracy is.”

– Sarah Botstein

“The rise of mainstream antisemitic rhetoric from powerful and influential people is frightening,” Botstein said. “America has a long and continuous history of nativism, racism, xenophobia and antisemitism. The current climate shows that this history is not only relevant but instructive, and should be a guide and a warning. These are dangerous times and we need to be vigilant. Our film is just one reminder of how precious American democracy is.”

The Florentine Films team is currently producing several new films. Botstein is working on a six-part series on the American Revolution and a project on President Lyndon B. Johnson’s life and presidency. Currently, “The U.S. and the Holocaust” can be streamed on the PBS website, PBS app and on all streaming devices.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.