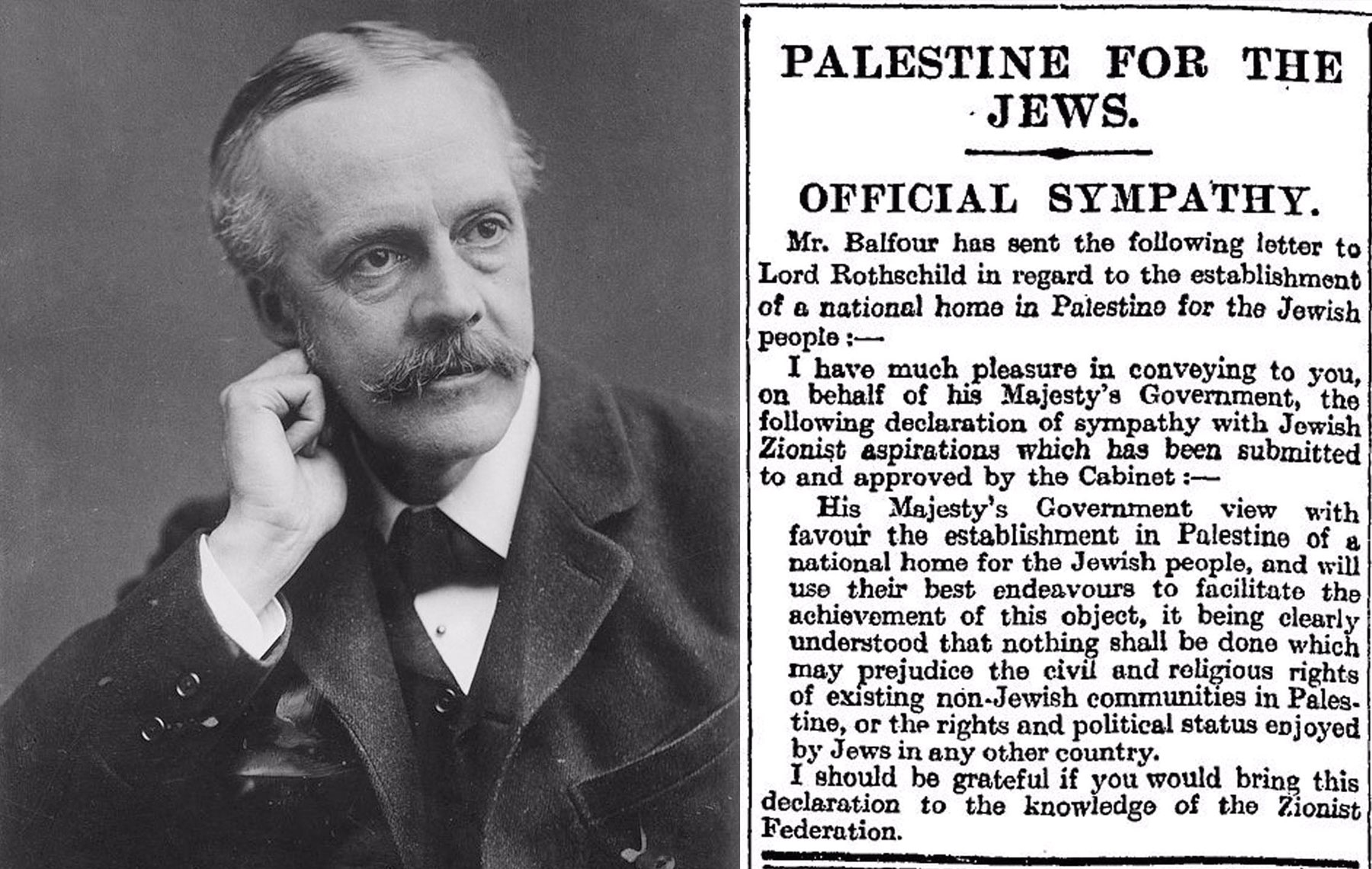

Arthur Balfour

Arthur Balfour One of the more interesting and telling social experiments is to ask someone the very simple question, “Who are you?” Have the person fill out 10 sentences, each of which start with “I am.” See where that leads in terms of self-perception.

My 4-year-old daughter, Liana, apparently has a very clear identity. “Who are you?” I asked. She did not say, “Liana.” Rather, she declared, “I am Jewish. I am Eyal and Nissa’s sister. I am Charlie and Stella’s friend.” This is her identity. This is her sense of self.

Teenagers also likely wonder, “Do I define myself as a jock, a student or an artist?” Adults ask, “Who am I?” all the time. Do I define myself as a lawyer, doctor or teacher? Am I happy or sad? Do I identify myself with my work, my family, my religion, my people?

For the Jewish people, when we ask ourselves, “Who are we?” an inextricable part of our identity is Israel. For almost 2,000 years, the Jewish people prayed for a return to the Holy Land and studied the laws of the land of Israel, imagining what this almost mythical place would be.

Little more than 70 years ago, the dream became a reality.

Yet, if we take an honest assessment of our knowledge about Israel, the triumphs and tribulations, the moments of pride and even the moments of shame, how many of us really know our story?

In the past decade, article after article has been written about how education about Israel needs to change. Some argue for the need to leave the world of dogma and allow more room for questions. Others argue for a multiple voice, multiple vision and multiple values Israel education. The case for a more rigorous approach to Israel education in general also has been suggested. Regardless of where you come out on this debate, one thing is clear: The time for an Israel education revolution is now.

If we take an honest assessment of our knowledge about Israel, the triumphs and tribulations, the moments of pride and even the moments of shame, how many of us really know our story?

In contrast to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Dewey, who emphasized the importance of social and intellectual skills over content and information acquisition, in his 1988 classic, “Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know,” E.D. Hirsch Jr. takes a different direction and demands a critical role for what he calls “cultural literacy.” He points out that each nationality has a different cultural story, and in an anthropological sense, the transmission of information from adults to children is vital for “community acculturation.” It is “only by accumulating shared symbols can we learn to communicate effectively with one another in our national community.”

Hirsch goes on to lament the limits of cultural literacy in U.S. society: Few students know Homer’s epic poetry included “The Iliad” as well as “The Odyssey”; few students know the years of World War II and forget World War I. Going deeper, Hirsch decries how few students know the date that the Declaration of Independence was signed, can name one of the first 10 amendments to the Constitution or state how many U.S. senators California has.

It is not that young people are ignorant, Hirsch explains. They often are quite knowledgeable about many aspects of life, but “what they know is ephemeral and narrowly confined to their own generation.” Good people can debate what constitutes the specifics of cultural literacy, but we ignore cultural literacy at our own peril. Hirsch explains, “Cultural literacy is the oxygen of social intercourse. Only when we run into cultural illiteracy are we shocked into recognizing the importance of the information that we had unconsciously assumed.”

For every nation, every country, every people, cultural literacy is necessary as background knowledge to communicate effectively. If we all can agree to value cultural literacy in the United States, how true is it for the Jewish people, as well?

Ponder these rhetorical questions: How many Jews in America have heard of the Titanic yet never heard of the Altalena? How many of us know the name of the mayor in our home city without knowing the name of the mayor in our homeland city (Jerusalem)? How many of our students can tell you every statistic about LeBron James but have not heard of the legendary American-Israeli basketball player Tal Brody?

Let’s dive deeper. Do our students know about the moral complexities and historical narratives of the 1948 Deir Yassin massacre? Can college-bound students speak intelligently about the deep Jewish connection to settlements and at the same time have empathy for the Palestinian experience in Judea and Samaria?

A good educational experience is one in which the learner comes out feeling like a stakeholder, not a ticket holder.

Taking all this into account, how can we ask our young people to go to college and advocate for Israel without knowing the history of Israel? How can we ask our young people to lobby for Israel without demanding they have cultural literacy? How can we ask our young people to represent Zionism when they often do not know what Zionism represents?

At Jerusalem U’s Unpacked for Educators, we’ve met this challenge head on by creating a new Jewish holiday season during November, which often falls around the Hebrew month of Marcheshvan. Rabbinic tradition has it that the prefix is “mar,” or “bitter,” because there are no Jewish holidays during this month. This lacuna of historic Jewish holidays means there is a ripe opportunity for a new holiday, with November becoming Israel History Month.

As educators busy with running the day-to-day lives of our schools, camps and youth groups, we often relegate much of our Israel education to the big days: Yom HaZikaron, Yom HaAtzmaut and for some, Yom Yerushalayim. When we are not celebrating these big days, we often focus more of our time and energy with students on combating anti-Semitism or preparing high school graduates for the challenges they’ll experience on campus.

Learning about the history and culture of Israel may not feel like it has the same urgency as these topics, but developing a generation of Jews that has a superficial connection to Israel is devastating when the story of Zionism is so remarkable and inspiring. Zionism is the world’s most successful national liberation movement. Russian British social theorist Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) said, “Israel has restored to Jews not merely personal dignity and status as human beings, but what is vastly more important, their right to choose as individuals how they shall live.” In a pithier way, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said on Dec. 9, 1910, “Zionism gives the Jews power to realize their dreams.”

Although the value of cultural literacy is unmistakable, that does not mean education is about telling people what to think. It is about giving them tools for how to think. Professor and historian Gil Troy pointed out in his 2018 book “The Zionist Ideas” that “modern Zionists would best turn some exclamation points into question marks while preserving some exclamation points.” This means our educational battle is not a difference of opinions, but of indifference. Our battle is not antipathy for Israel, but apathy. Our battle is to ensure our young people have self-confidence in their story, without feeling like they know it all.

Although it may seem like a big ask, it doesn’t need to be. That’s why Jerusalem U’s Unpacked for Educators has created Israel History Month throughout the month of November because November is a month pregnant with educational opportunities for both literacy and connection to Israel.

Developing a generation of Jews that has a superficial connection to Israel is devastating when the story of Zionism is so remarkable and inspiring.

November is a month of both tragedy and triumph in the chronicles of modern Israeli history. These include the Balfour Declaration (Nov. 2, 1917), the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin (Nov. 4, 1995), the “Zionism equals racism” U.N. resolution (Nov. 10, 1975), the start of Operation Moses (Nov. 21, 1984) and the passage of the Partition Plan (Nov. 29, 1947).

Let’s take a quick glance at each of these days and some questions they might bring up.

On Nov. 2, 1917, Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour of Great Britain wrote a letter promising a “Jewish home” to the Jewish people in the land of Palestine, which the League of Nations ratified in 1922. Why does this document carry so much significance? What are ambiguities in the text? Why does it matter today?

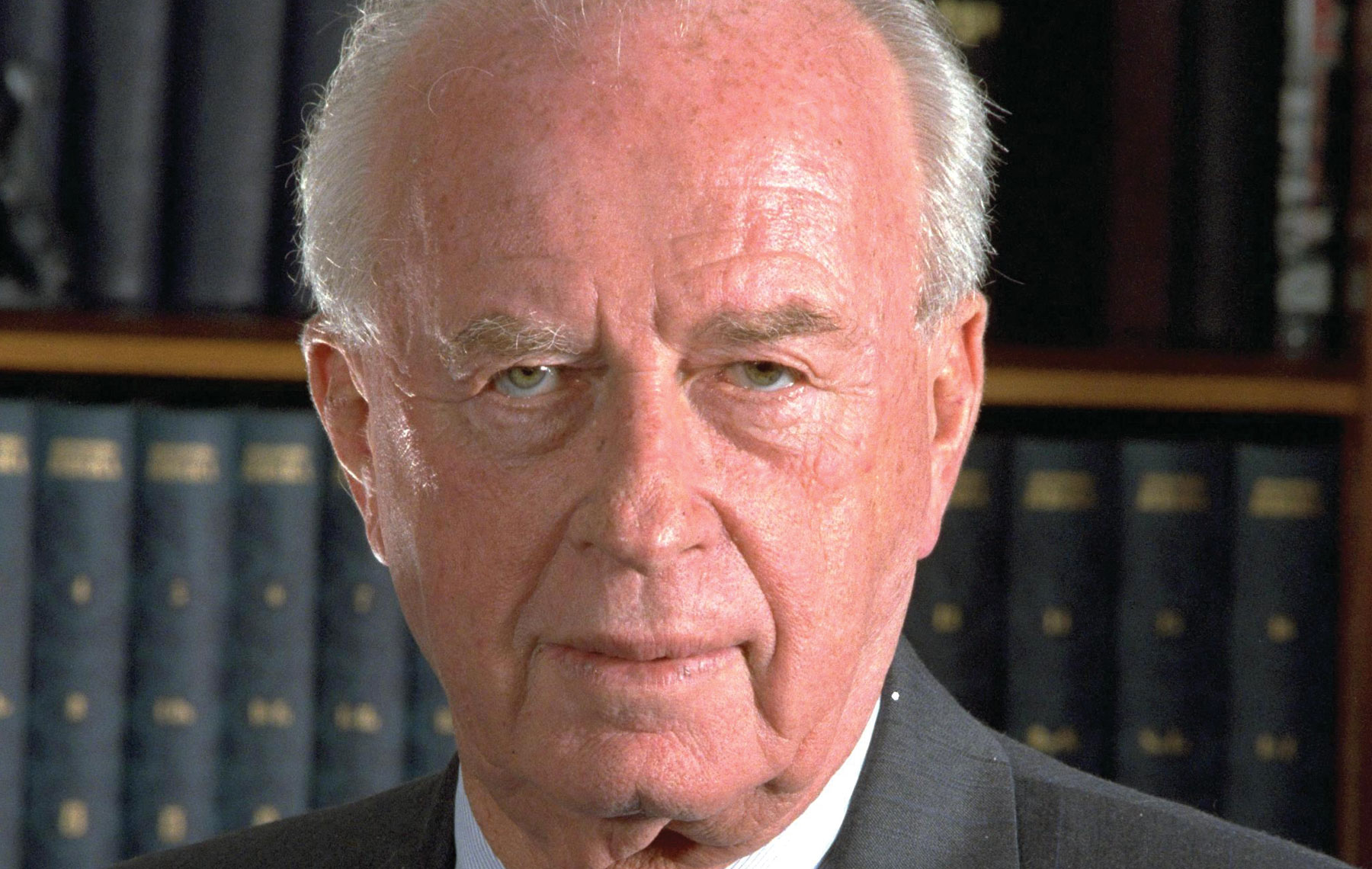

On Nov. 4, 1995, Rabin was assassinated. He was a man of paradoxes, a man of responsibility. Admired by many and abhorred by some, Rabin fought tenaciously for both security and peace, but what do we know about this man?

On Nov. 10, 1975, just 37 years after Kristallnacht, the United Nations declared that “Zionism is racism.” This was repealed in 1991, but it raises the question: Why is the United Nations so focused on Israel? Are there reverberations of this declaration today on college campuses?

Beginning Nov. 21, 1984, Israel engaged in Operation Moses, bringing thousands of Ethiopian Jews to its shores. This “ingathering of exiles” or “kibbutz galuyot” has been part of Israel’s raison d’etre from the beginning. What is Israel’s relationship with world Jewry? What does it mean to be a Jew in the eyes of the Israeli state? How far will Israel go to take responsibility for Jews worldwide? Ultimately, what is a home?

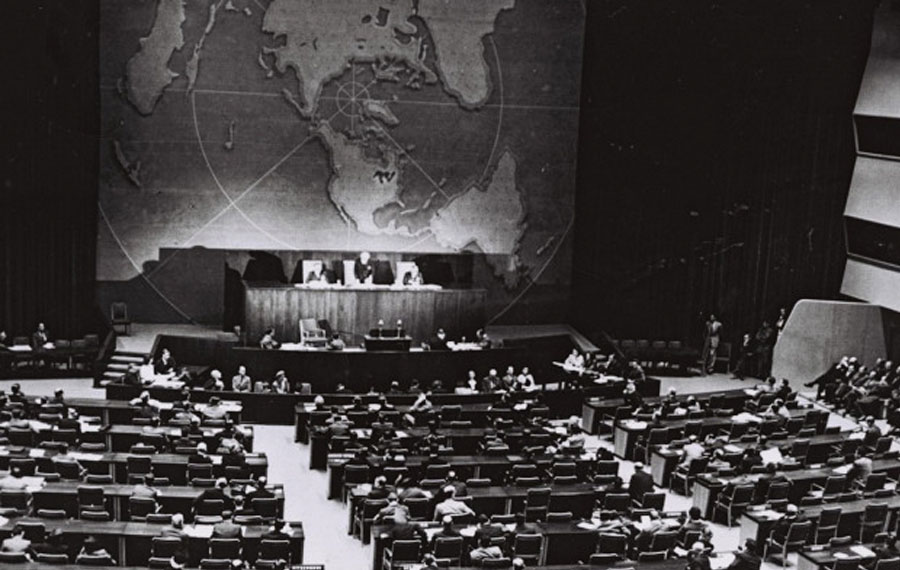

One of the most momentous days in Jewish history was Nov. 29, 1947. Just two years after the Holocaust nearly decimated European Jewry, the world voted there ought to be a Jewish state with U.N. Resolution 181, also known as the “Partition Plan.” This plan was to divide the land into two states: one Jewish and one Arab. What led up to the resolution and what were the considerations and reactions to it? How did the Jewish and Arab communities react to the resolution? Why was this resolution one of the most remarkable in the history of the United Nations?

For every nation, every country, every people, cultural literacy is necessary as background knowledge to communicate effectively.

Each of these events affected Israeli and Jewish history in different ways and form much of the basis for understanding different aspects of Israel.

We partnered with M2, the Institute for Experiential Education, to take our digital content and develop experiential learning activities. With these activities, students can explore the values and tensions inherent in the films. Some educational institutions may choose to spend a few hours on each topic, while some may choose to spend only 10 to 20 minutes. There is no right or wrong way of teaching about these events — or even which events should be taught. That’s up to each institution to decide.

Imagine how meaningful it could be to take a Hebrew language class to explore the backstory of the Balfour Declaration. For a Jewish history class to unpack the U.N. resolution that declared Zionism racism. Think about the impact it might have on a youth group to study the life and times of Rabin by watching a video about him, then reflect on the magnitude of his assassination. Consider how a whole school can leverage assembly time to celebrate Operation Moses, then have a sophisticated conversation about different ethnic groups in Israel. A synagogue could commemorate Nov. 29 each year by watching our video on U.N. Resolution 181 and learning about the values of compromise.

It is not just for formal educators, but all adults in the community. When I travel to different cities to describe the importance of Jerusalem U’s work, I inevitably hear a version of these questions: “Forget the teenagers. What do we do about the 30-year-olds who are apathetic about Israel? What do we do to engage parents who are too exhausted to spend time learning about their Jewish story? What do we do to engage the parents who influence the kids?”

Here are four suggestions to incorporate an educational connection to Israel based on Unpacked for Educators:

- All pro-Israel advocacy organizations should send out weekly videos on the story of Israel so their constituents know the broader story of Israel.

- Local Jewish community centers or federations can send out content each week or each month with discussion questions to have at the dinner table.

- Include in your Shabbat dinners reflection opportunities to internalize the unique achievements and contributions of Zionism and the Jewish state.

- Read our weekly digest of current events and use an empathic approach to dialogue and debate.

Yes, it can be daunting to fit so many topics into our curricula, and the dinner table can be riddled with all sorts of conversations — but learning about Israel and internalizing our connection to the State of Israel, the people of Israel, the challenges of Israel and the celebrations of Israel deserve our attention.

A good educational experience is one in which the learner comes out feeling like a stakeholder, not a ticket holder. This is only possible when there is cultural literacy — when we own our story.

So, this month of November and every month of November, join us in making it Israel History Month. Grab your phone, sign on to your computer, watch our videos and discuss the implications. Let’s all have strong opinions, different perspectives and even conflicting worldviews; let’s also remember we all have a seat at the table when we own our story. And when we own our story, we can answer the question, “Who am I”?

Noam Weissman is the senior vice president of education at Jerusalem U.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.