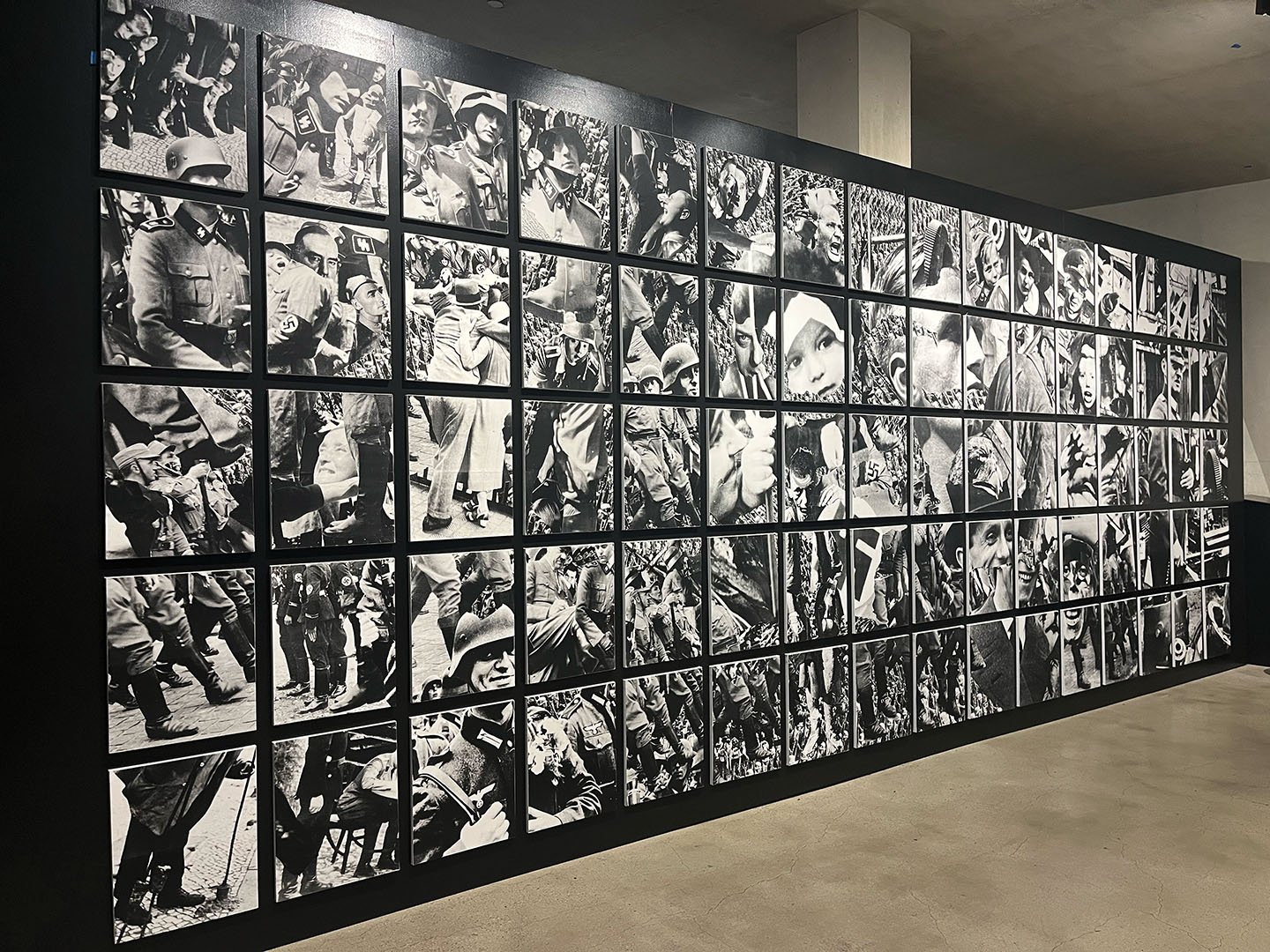

“Die Plage,” a monumental new art exhibition at Holocaust Museum Los Angeles, is an artistic exploration tracing German history throughout the first half of the 20th century — from the Weimar Republic that was established after the end of World War I through the atrocities of the Holocaust during World War II.

Created by the late avantgarde artist Harley Gaber, “Die Plage” — German for “The Plague” — consists of collaged photographs, including archival images from Germany that Gaber photocopied and manipulated using razor blades and scissors. His images show Bauhaus architecture; uniformed Nazi soldiers; worked-up German crowds at rallies; and Jewish victims of Nazi crimes.

Gaber has reworked, resized and recontextualized the images. The result is an intense and reimagined history offering themes that continue to resonate today — specifically, the ease in which an individual can be swept up in the sociopolitical currents of the time.

Gaber has reworked, resized and recontextualized the images. The result is an intense and reimagined history offering themes that continue to resonate today — specifically, the ease in which an individual can be swept up in the sociopolitical currents of the time.

“We are all collages — we’re different people with different experiences,” Jordanna Gessler, chief impact officer at Holocaust Museum LA, told The Journal. “So, the exhibition is also examining the idea of a collage and how Gaber used collage as an artform.”

On Feb. 6, “Die Plage” opened at Holocaust Museum Los Angeles.

Gaber was born in 1943 in Chicago. He was raised in an unobservant Jewish family and was influenced by Buddhism. Before turning to the visual arts, he was an acclaimed minimalist composer. His compositions from this period in his career, including the groundbreaking album, “The Winds Rise in the North,” incorporated Eastern religion and philosophy.

In 1978, Gaber moved from New York City to La Jolla, California and gave up music composition to focus on collage-making. His eventual work on “Die Plage” utterly consumed him. Though he had no personal or familial connection to the Holocaust, he was inspired by multiple trips to Germany in which he explored archives and historical sites and visited former concentration camps.

“Die Plage” was Gaber’s largest undertaking. Beginning in 1993, he spent 10 years creating the canvases for the installation, laboring over each image, often throwing away pieces out of frustration. In 2002, he completed the mammoth project.

Adding to the tragedy surrounding Gaber was his decision in 2011 to take his own life. He was 68 at the time.

Chicagoan Dan Epstein, who knew Gaber from growing up together, recalled the unexpected phone call he received from Gaber when the artist informed him of his plans to take his life. He told Epstein to grab a pencil and proceeded to give instructions to Epstein on how to retrieve the canvases from a storage space in Oregon that comprised “Die Plage.”

On Feb. 6, a panel discussion with Epstein and several others marked the exhibit’s launch at Holocaust Museum LA. Two of the people on the panel — Epstein, founder and president of the Chicago-based Dan J. Epstein Family Foundation, and Mark Breitenberg, an arts educator — knew Gaber. They described him as having an artist’s temperment — challenging, depressive, often broke and living hand-to-mouth.

They also described him as an “iconoclast.”

Exhibit curator Melissa Martens Yaverbaum and Judy Margles, director emerita of the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, rounded out the panel. Approximately 100 community members — including Gaber’s brother, Steve; his former girlfriend, Christina Ankofska; Holocaust survivor Erika Fabian and Holocaust Museum LA CEO Beth Kean—were in attendance.

Margles, who retired from her role at the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education and served as a consultant on bringing the work to Los Angeles, said the themes of Gaber’s photo montages continue to resonate in today’s climate.

“No matter where we are in history, I think there will be relevance for Harley’s work,” she said. Referencing those who argue the Holocaust didn’t happen, “People are trying to erase these memories,” she said, emphasizing the importance of Gaber’s work.

After the panel, as a crowd of people made their way through the exhibit, the musical group, Bauman Trio, performed.

A live music group was appropriate. In a nod to Gaber’s extensive musical background, the monumental work of “Die Plage” is understood to be divided into four distinct movements. Blank white canvases appear alongside canvases filled with collaged, photo-montaged images. They are intended to serve as visual “pauses,” just as the rests in a composition offers a brief pause.

The entire work has about 4,200 canvases. But on display at the at the museum in Pan Pacific Park are 600 of these canvases. They cover six walls and are arranged in grid-like formations, per Gaber’s original design and intention. Among the canvases are images showing the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin.

With the approach of the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, Holocaust Museum LA felt these were important and timely to include, Gessler told the Journal.

The exhibit also has items from Gaber’s life, including family photographs and sheet music from his musical scores. There’s also video showing the artist at work.

For Epstein, president of the family Foundation that manages Gaber’s body of work, seeing people view Gaber’s artwork at Holocaust Museum LA was particularly gratifying. He’s made it his mission for as many people to see Gaber’s “Die Plage” as possible.

“My foundation owns this, and my goal is to find a home for it, a permanent home that will honor it, exhibit it and research it,” Epstein said. “It’s not financial. I just want ‘Die Plage’ to find its place in the 21st century and to be well known and be respected.”

“Die Plage” remains on display through June 30. For information on how to view the exhibition, visit holocaustmuseumla.org/die-plage