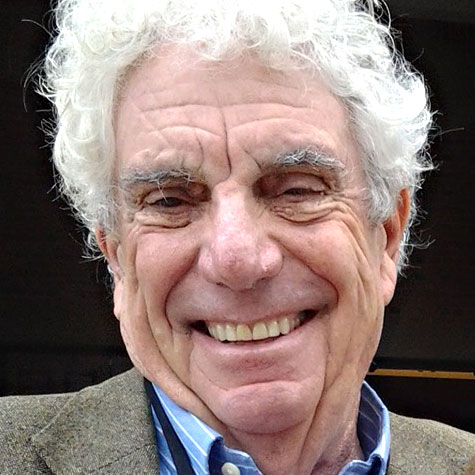

Rabbi Marvin Gross’ congregants include Los Angeles County’s poorest, most neglected and most scorned — the homeless.

As chief executive officer of Union Station Homeless Services, Gross and his staff find housing, medical and psychological care, and help locate training programs and jobs for homeless women, men and children in the San Gabriel Valley. These suburbs are not usually associated with the tents and tarpaulins of the street encampments on Los Angeles’ Skid Row or those under the Hollywood, 405 and other freeways. It shows how far homelessness has extended and how deep it reaches into society.

“I look at the people at Union Station, in a way, as my congregation,” said Gross, 68, who was rabbi of Temple Sinai of Glendale for 7 1/2 years.

I met him while doing columns on the homeless for the website Truthdig. Union Station is one of the nonprofit organizations on the streets every day fighting a fast-growing onslaught of homelessness that has not been given much attention from any level of government. Volunteers from All Saints Episcopal Church in Pasadena started Union Station in 1973.

“It was founded on Union Street in Old Pasadena, which was then a slum,” Gross said. The volunteers named their project after the street. “They decided to put up a little a storefront to provide kindness and a haven to the men who lived in the flophouses in Old Pasadena.”

The situation has gotten a lot worse since then. The National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty estimates that, in the United States, 2.5 million to 3.5 million sleep in shelters, temporary transitional housing and on sidewalks, in parks, underneath freeways, and on buses and trains. The center estimates that an additional 7.4 million live with relatives or friends after losing their own homes. These figures, the center said, “are far from exact,” coming from several sources, each with their own way of counting the homeless. But they reflect the depth of the problem.

There are 25,686 homeless in the city of Los Angeles, the largest city in Los Angeles County, where the homeless number 44,359, according to the annual homeless census taken by Los Angeles County and nonprofit agencies.

As the homeless situation worsened, Gross got involved. He had been an activist while on the pulpit, active in the efforts to limit nuclear arms and and as an advocate for many social justice issues. “I got a little restless,” he said. He resigned from his rabbi’s post, “and I started to work for Sen. [Alan] Cranston when he ran for re-election in 1986. I believed in him and all his positions on Israel, Soviet Jewry, the nuclear arms race.” From there, Gross went to work for The Jewish Federation of Greater Los Angeles.

He was encouraged to apply for the post of leading Union Station by the Rev. George Regas, rector of All Saints, whom he met while working with the interfaith center at the church on ways to limit the arms race.

“We have been able to serve many more people in many more ways since I took over,” he said. “We [then] had one facility, one program, 22 staff people, a budget of $930,000 a year and strong support from the community, which continues today. Today, we have 10 major programs. We have five sites in Pasadena. We have 90 employees; we continue to have a great board of directors, hundreds if not more community volunteers, and our budget is about $8 million in this current year.”

The complexity of the organization’s task is illustrated by Gross’ analysis of the homeless. A common view of the homeless is that they are hopeless addicts, mentally ill or both. Gross and others in homeless relief say the picture isn’t so simple.

“We have seen changes in the demography of who is homeless in this area,” he said. “When I came to Union Station, it was mostly men and a few women. They were white, Black and brown. Mostly white and Black. And now we have almost as many single women as we do men. We’ve had a huge increase in families over the years.

“Everyone has a different story, but basically the families are single mothers — single mothers with very limited job skills. Sometimes they have their own personal problems with drug abuse or other kinds of addiction or mental illness. Sometimes, it’s two-parent families, sometimes a father with kids, people who are low income, maybe because of the recession. They were unable to pay their rent and were evicted. Sometimes they have children with special needs who require extra support. Maybe they live with a sister or an aunt, and that gets old and then they’re living in a car. We’ve had families who lived in cars and [went] from church parking lot to church parking lot, then onto the street.”

I recently saw close up how Gross reaches his congregation of the homeless. I spent a morning with Logan Siler, 31, an outreach worker for Union Station Homeless Services. His job is to cruise the streets of Pasadena in a van, always on the lookout for someone who might be homeless. He knows the spots under freeway overpasses and parking lots where they gather. Or he sees one or two on the streets.

His task is to engage them in conversation, learn their stories and fill out a long questionnaire, probing their histories of homelessness, illness, family status and other personal details. At day’s end, Siler enters the information in a countywide database. On a 1-to-10 scale, the homeless are rated on the seriousness of their conditions. Those most in need of help are given a higher priority for scarce housing. Housing, usually in apartments, is found by Union Station and other nonprofits, which have stepped in as government has stepped out.

On this day, Siler spotted a man near the 210 Freeway, standing alone — slender, middle-aged, wearing shorts and a blue sweatshirt. The outreach worker, who previously worked with young people in San Francisco’s Haight, pulled over. He motioned me to stand aside so he could talk to the man privately. He gave him a bag lunch and began chatting in a friendly manner. They sat down on the sidewalk in the shade of the freeway overpass. They were there for a half hour while Siler filled out the questionnaire and told the man about the services available at Union Station. Hopefully, he went there.

That’s how Gross and his staff do their jobs, sometimes one homeless person at a time. It’s tough and frustrating work, but in a time when homelessness has become a neglected national tragedy, their efforts are as important as anything a rabbi can do.

Bill Boyarsky is a columnist for the Jewish Journal, Truthdig and L.A. Observed, and the author of “Inventing L.A.: The Chandlers and Their Times” (Angel City Press).

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.