The language of Middle Eastern politics can be frustrating, when one realizes, for example, that a ceasefire does not mean that the combatants have ceased firing at each other. So those who refer to the ceasefire between Israel and Hezbollah, which has been marked by violence every day since its inception, as “fragile” may be giving it more credit than it has yet earned.

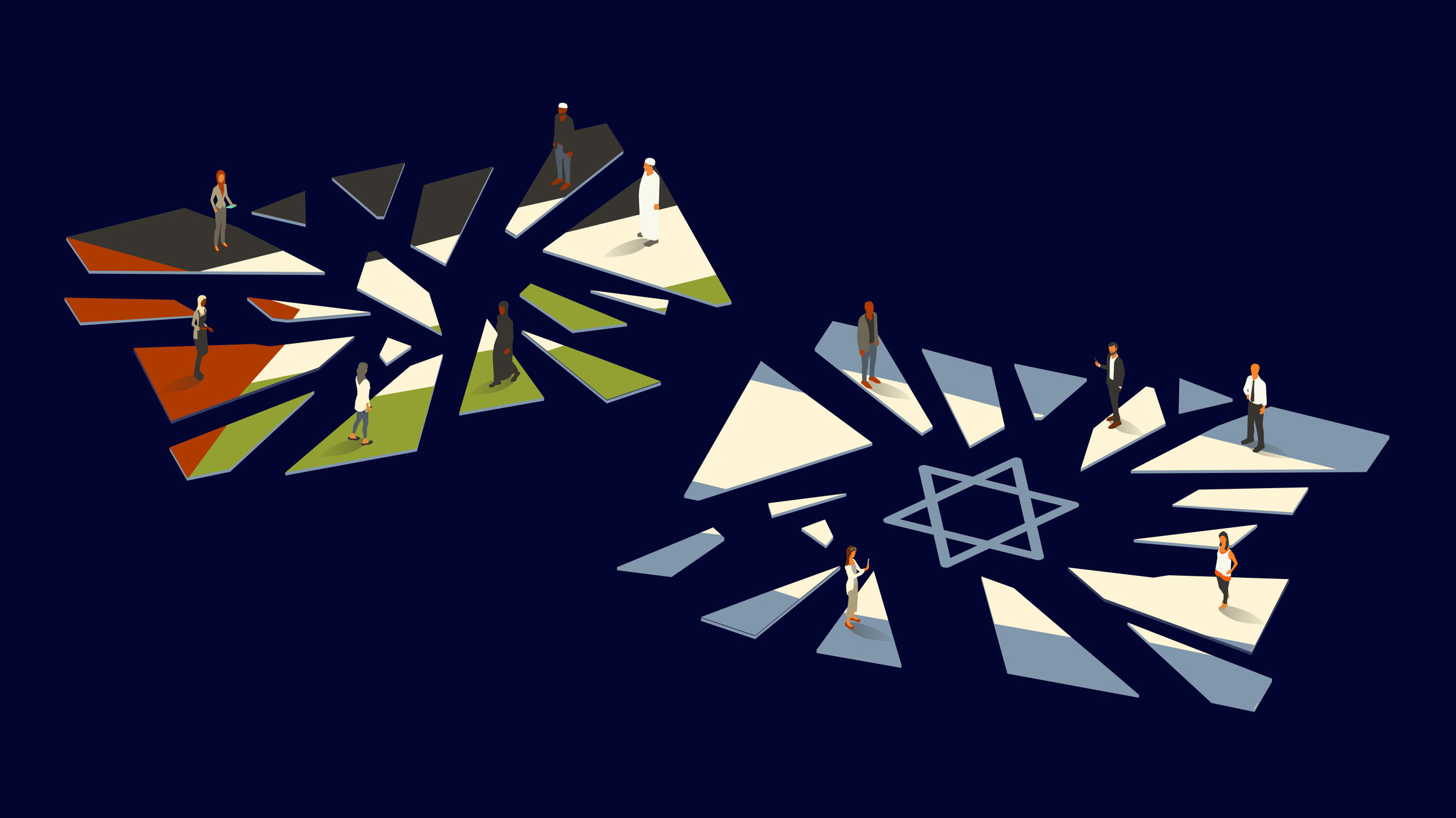

But even a misnamed agreement between the Jewish State and an armed proxy of Iran represents notable progress, and it’s no longer fantastical to discuss whether it could open possibilities for a cessation – or at least diminishment – of hostilities with Hamas, the Houthis and the other members of the Iranian terrorism-for-hire cabal that surrounds Israel to the north, east and south. Hamas now faces the prospect of continuing its fight against Israel without its most aggressive ally, and Iran itself has looked almost defenseless in the face of Israeli aerial attacks. For the first time in recent memory, envisioning the treacherous path toward peace — or at least calm — can rely on ardent optimism rather than utter delusion.

But let’s not get carried away just yet. Hezbollah’s willingness to negotiate comes not from enlightenment but from vulnerability. Israel’s participation is driven not by farsightedness but exhaustion. But other uneasy armistices have been built on less high-minded motivations.

At the same time, several other recent developments in the region have added both complications and opportunities to potential next steps forward. The most visible of these events is in Syria, where Iranian ally Bashar al-Assad’s troops have been routed by a rebel coalition after many years of impasse. These opposition forces have pushed Assad’s armies out of the key city of Aleppo and appear poised for even bigger gains.

On the multidimensional chessboard that is the Middle East, Assad’s inability to suppress the insurgency reflects not only his own impotence but is another sign of Iran’s growing weakness. When Assad was facing a likely defeat at the hands of his opponents back in 2016, he was saved by massive direct intervention from Iran and Russia. But the war in Ukraine now prevents Vladmir Putin from coming to Assad’s rescue, and most of the region will be watching closely to see to what degree Iran can afford to involve itself given the losses its own military has suffered at the hands of Israel.

On the multi-dimensional chessboard that is the Middle East, Assad’s inability to suppress the insurgency reflects not only his own impotence but is another sign of Iran’s growing weakness.

No one is watching more closely than Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, whose fear of Iran has been the impetus behind his keen interest in formalizing his country’s relationship with Israel. A Saudi-Israeli partnership would fundamentally and historically remake the Middle East: This is the stuff that legacies – and Nobel Peace Prizes — are made of. Little wonder that Benjamin Netanyahu, Joe Biden and Donald Trump all dream of such a deal.

But the Saudis made it clear last week that they are no longer nearly as willing to compromise to achieve a military agreement with Israel, saying that the Gaza War had made such a pact much more difficult to accomplish. MBS had previously indicated that a broad public commitment from Israel toward the establishment of a Palestinian state even without tangible guarantees would be sufficient for him to move forward. But the anger toward Israel throughout the Arab world is so intense that the Saudi leader will now only sign on to a treaty if Israel takes more concrete steps toward a two-state solution. And of course, this is something that Netanyahu’s current governing coalition would not allow.

In the midst of various pronouncements from Riyadh and Tel Aviv, from Tehran and Beirut and Damascus, it’s notable that the one center of geopolitical relevance from which we had not yet heard is Mar-a-Lago. Trump has made it clear he wants the fighting in Gaza to have ended before his inauguration, and has threatened Hamas with dire consequences if the hostages are not released by then. More than any other player in this drama, the president-elect may now have the strongest say in whether this almost-ceasefire is a one-act play or the beginning of something bigger.

Dan Schnur is the U.S. Politics Editor for the Jewish Journal. He teaches courses in politics, communications, and leadership at UC Berkeley, USC and Pepperdine. He hosts the monthly webinar “The Dan Schnur Political Report” for the Los Angeles World Affairs Council & Town Hall. Follow Dan’s work at www.danschnurpolitics.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.