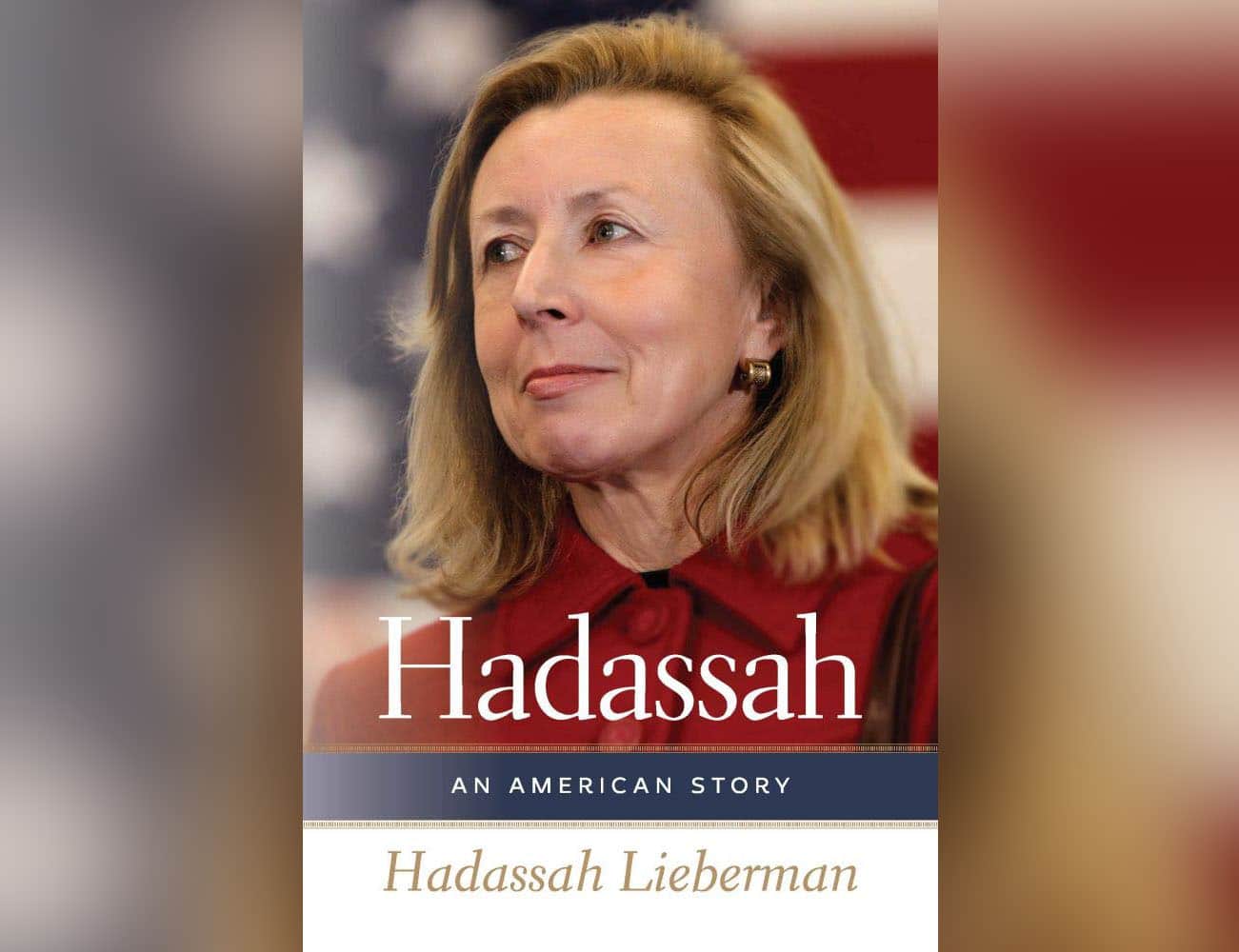

Hadassah Lieberman does something unusual in her memoir — she includes observations from her four children. In doing so, this daughter of Holocaust survivors is making a statement: “Their existence represents my ultimate defiance of Hitler’s goal: the extermination of the Jewish people.”

In “Hadassah: An American Story,” published by Brandeis University Press as part of their HBI Series on Jewish Women, Lieberman voices the pain she carries as the daughter of survivors, her gratitude as an immigrant and naturalized citizen and her alarm over what she sees as increasing xenophobia now taking hold. Whether writing about marriage, motherhood, illness, being on the campaign trail or an official visit to the concentration camps, Lieberman expresses herself with honesty, dignity, heart and wisdom.

Born in Prague in 1948, Esther (Hadassah) Freilich was the daughter of Ella Wieder Freilich, a survivor of both Auschwitz and Dachau, and Rabbi Samuel Freilich, who was conscripted by the Hungarian army during World War II. Of the 60,000 Hungarian Jews conscripted, only 15,000 survived. By the war’s end, Rabbi Freilich had typhus, was blind in one eye and weighed only seventy pounds. But he was alive. After the war, Samuel and Ella met and married in Prague, then immigrated to the United States when Hadassah was a baby and the Soviets had taken over the Czech Republic.

Lieberman chronicles her parents’ lives and experiences in the first chapters as a way of bearing witness. Her mother, she shares, suffered frequent nightmares from her war experiences but was “a force of nature… the memories she leaves with us and the lessons she taught are now part of our life force. They are her legacy to us—our responsibility to keep alive.” Lieberman also relates that “Even in the face of calamity my father always believed there was some purpose to everything in life.” These questions have infused and animated Lieberman’s life, teaching her how to make a difference and how to live a life of meaning that is also faithful to Jewish tradition.

Hadassah grew up in a small New England town where her father worked as a rabbi. She married Rabbi Gordon Tucker and had one son with him. When her marriage ended in divorce and she became a single mother, she felt that “the foundation that I built my life on was crumbling.” However, she soon realized that “the possibilities of the future are more endless and positive than are the difficulties of the past. The future was something I held in my own hands.”

In 1982, a mutual friend suggested that Joe Lieberman, who was then running for Connecticut attorney general, meet Hadassah, who was then living in New York with her young son. Joe was also divorced with teenagers — a son and daughter. Despite the hurdles of dating — given his campaign schedule, physical distance and their obligations to their jobs and their children — their attraction was instant and mutual. Joe helped Hadassah overcome her reticence about a second marriage for several reasons: she recognized that his ambition was “not to hold public office merely as an end in itself” but for the goal of tikkun olam — repairing the world. He also played board games with her son, who liked him very much. And yes, she thought he was handsome, too.

Although they had a blended family, the Liebermans “made a conscious decision” never to refer to any of the children with the “step” prefix. (The couple had a daughter together in 1988, during Joe’s first senate campaign.) According to Hadassah, their full embrace of each child “and verbalizing them as full children… made a critical difference to us. I consider this my greatest accomplishment: creating a fully integrated, tightly knit, and loving family.”

“I consider this my greatest accomplishment: creating a fully integrated, tightly knit, and loving family.”

After Lieberman won his campaign, the family moved within walking distance of the Senate because as the first Shomer-Shabbat senator, Joe planned to vote even on a Friday night or Saturday. “His personal religious convictions mirrored his approach to serving his country… The private went hand in hand with the public,” she writes.

Hadassah’s career in the healthcare field was interrupted when she became a Senate wife. But in Washington, she became a consultant on educational issues, public affairs and global women’s health issues. Everything in her life became more complicated since she and Joe were in the public eye, but she accepted that “it was all part of the job.”

The couple’s prominence grew when Vice President Al Gore tapped Senator Lieberman as his running mate for the presidential election of 2000. Hadassah campaigned actively, often “speaking from the heart” as opposed to from a prepared script, emphasizing her story as an immigrant living out the promise of America. Even during the campaign, the Liebermans’ Shabbat observance was non-negotiable: “To us, the Sabbath was just as important as making an extra campaign stop—more important actually. If we didn’t stay true to who we were, what was the point of running for office in the first place?” Joe and Hadassah both refused to check their religious beliefs on the campaign trail, despite advice to the contrary. The Gore-Lieberman ticket won the popular vote but lost by a single vote in the electoral college after the Supreme Court affirmed the legitimacy of contested votes in three Florida counties.

Hadassah Lieberman expresses no rancor or bitterness over political or personal disappointments. Instead, in this slim but substantial memoir, she expresses gratitude for her life of privileges and challenges, showing how she has worked “to establish a distinct identity as Hadassah Freilich, Hadassah Lieberman and as just plain Hadassah, so that I can make a difference in places where I was previously unknown.”

Judy Gruen is a writer and editor. Her books include “The Skeptic and the Rabbi: Falling in Love with Faith.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.