Photo from Flickr.

Photo from Flickr. “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” stated German philosopher Theodor Adorno.

Jews did, of course, create all types of art after World War II, even works of great beauty. But what about the young Jewish artists who came of age right after the Holocaust?

Stanley Kubrick was born in the Bronx in 1928. His maternal grandmother spoke Yiddish, but his home was not religious. (He once said he was “not really a Jew, but just happened to have two Jewish parents.”)

Yet Kubrick certainly felt the awkwardness of being an outsider, a theme that turned up frequently in his films. He confronted blatant anti-Semitism — he was barred from restaurants and hotels in the South and was denied a table in Vermont. Even Hollywood was far from receptive early on. “Get that little Jewboy from the Bronx off my crane,” famed cinematographer Russell Metty once grumbled.

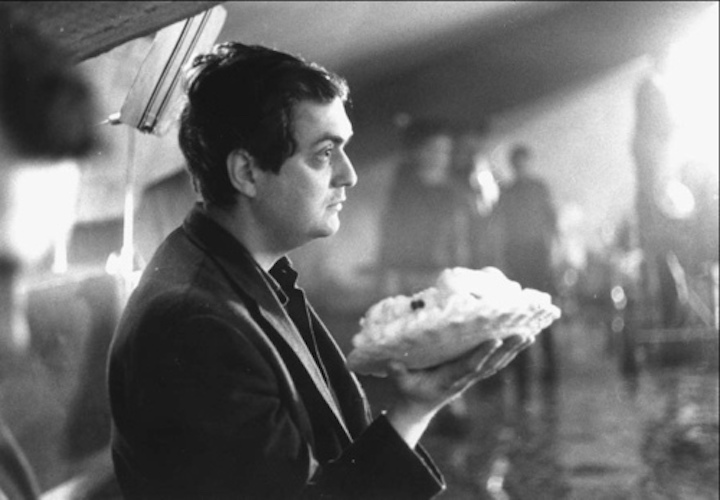

Kubrick’s observant sense of the outsider no doubt fueled the innovative brilliance of his early photographs. A new exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York, “Through a Different Lens: Stanley Kubrick Photographs,” focuses exclusively on Kubrick’s early work as a photographer for Look magazine. In 1945, at just 17, he sold his first photo to the magazine — an image of a dejected newsstand vendor the day after the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In the exhibition’s 130 images, you can see Kubrick’s uncanny artistic sensibility, finding inspiration in New York’s characters and settings. An acute observer of human interaction, Kubrick was brilliant at capturing the grit and dark glamour of the city — nightclubs, street scenes, sporting events — and trained his eye to capture poignant moments. He spent five years at the magazine, until he began work on his first independently produced documentary, “Day of the Fight.”

The exhibition’s curators claim Kubrick’s photography laid the technical and aesthetic foundations for his iconic films. In terms of framing, lighting and composition, that would appear to be the case. There is even a poetry to some of them, however dark.

In a new book, “Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual,” author Nathan Abrams asserts that if you look closely enough, the tension between being a cultural and religious Jew turns up frequently in Kubrick’s work.

Kubrick consistently worked with Jewish writers and actors. In general, Kubrick obfuscated the Jewishness of some of his characters, but expanded the roles that were “coded” for Jews. “2001: A Space Odyssey” plays with the Bible, Jewish liturgy and kabbalah. And Abrams argues “Eyes Wide Shut” is Kubrick’s most Jewish film, adapted from a Jewish author and heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud.

But what’s most apparent in Kubrick’s films is the extraordinary effect the Holocaust had on him. According to Abrams, Kubrick read every word he could find on the subject. He became obsessed with darkness, perversity and evil, and with what it took for a soul to go from light to dark, for humanity to die on the inside.

Nazi or Holocaust references turn up frequently in his films. Out of nowhere in “Lolita” the title character shouts “Sieg Hiel!” at her mother with a Nazi salute. “Dr. Strangelove” is about the mundane processes of mass murder. “Full Metal Jacket” sports Naziesque generals. Kubrick’s films are filled with explosives, gunfire, firing squads and bombs.

Did the Holocaust destroy Kubrick’s own soul? There is little beauty — poetry — in Kubrick’s films. He ended up fulfilling Adorno’s most famous quote.

For the last 20 years of his life (he died in 1999, at 71), Kubrick worked on “Aryan Papers,” based on Louis Begley’s “Wartime Lies,” about a Jewish boy pretending to be Catholic to survive the war. But he was never able to finish it and was known to be very depressed when working on it.

This may have been for the best. A Kubrick Holocaust movie would probably have been unbearable to watch.

Karen Lehrman Bloch is an author and cultural critic.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.